This is the third post in a series on national disaster reforms. The first post outlined principles for reform, and the second focused on changes to the federal disaster declaration process.

This summer’s Northeast floods and Southwest heatwaves are just the latest examples of what is becoming an endlessly growing burden of costly and life-threatening climate events. As climate change continues to bring these unprecedented hazards and costs to U.S. communities, there are growing calls for demonstrable equity in treatment and outcomes by the public agencies charged with disaster response, relief, and recovery.

But the budgets, staff, organization, and operations associated with the Disaster Relief Fund—which supports federal disaster management programs—are hard-pressed to keep up. This has resulted in Congress increasingly directing other programs across federal agencies to play key roles in disaster mitigation, relief, response, and long-term recovery and resilience.

Yet to eliminate the cracks that vulnerable disaster survivors fall through, our federal disaster response requires a central administrator. In this piece, we argue for congressional action to elevate the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to an independent cabinet agency and grant it authority over federal emergency decisions. We also outline how FEMA’s statutory mission and programmatic operations must be recalibrated to manage long-term social, economic, and environmental risks in hazard-prone places. FEMA must better coordinate with other federal agencies that focus on making communities safer, as well as with the federal safety net programs that support survivors. This will require a change in FEMA staff’s historical professionalization, improvement in FEMA management systems, and a commitment to streamlining federal interventions in communities.

The US has faced a management crisis in federal disaster policy for decades

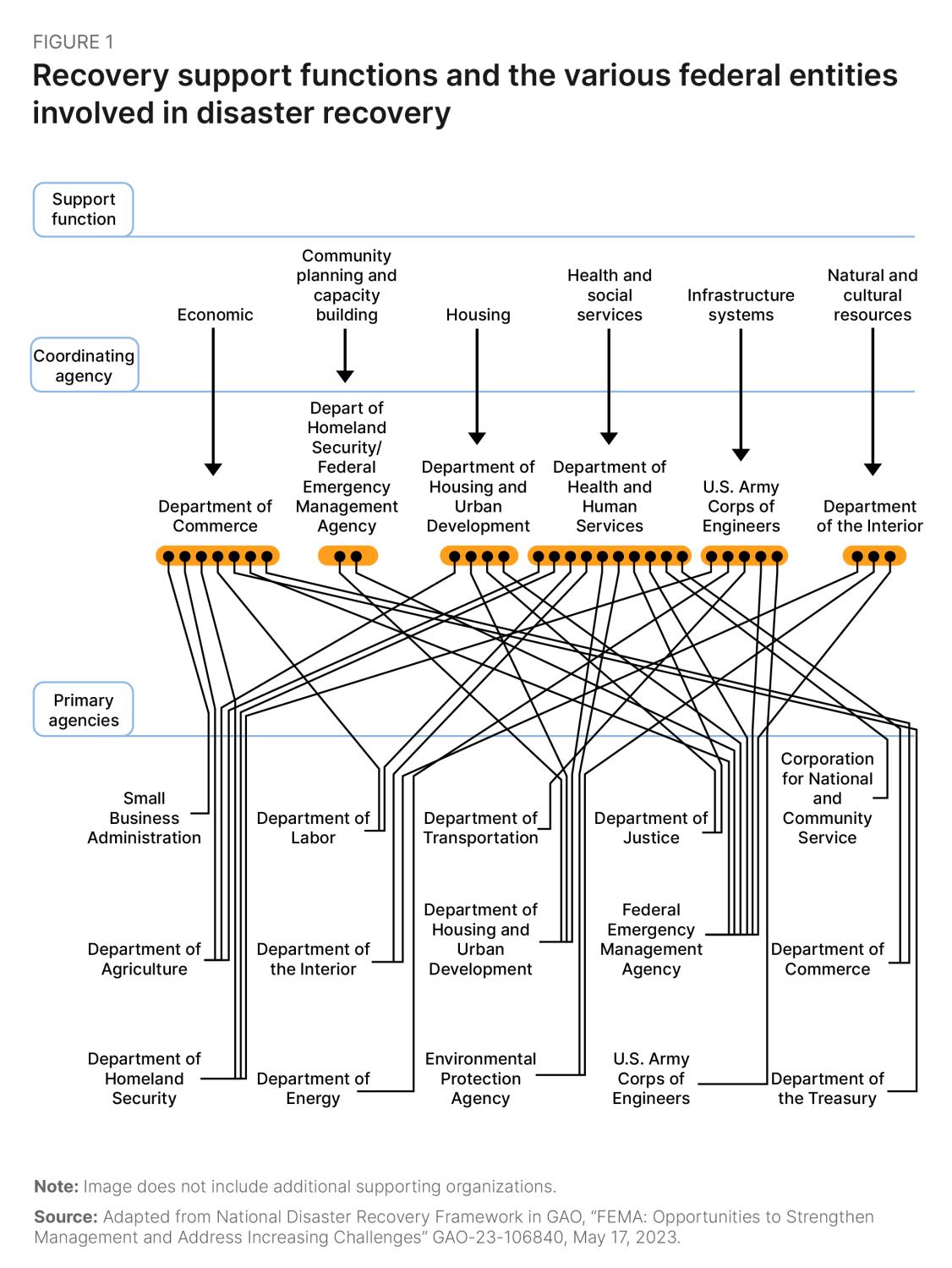

The current federal disaster management structure is labyrinthian: Five “mission area frameworks” spread across 32 “core capabilities” that involve dozens of federal programs in multiple cabinet and non-cabinet agencies, each with its own support function and coordinating role.

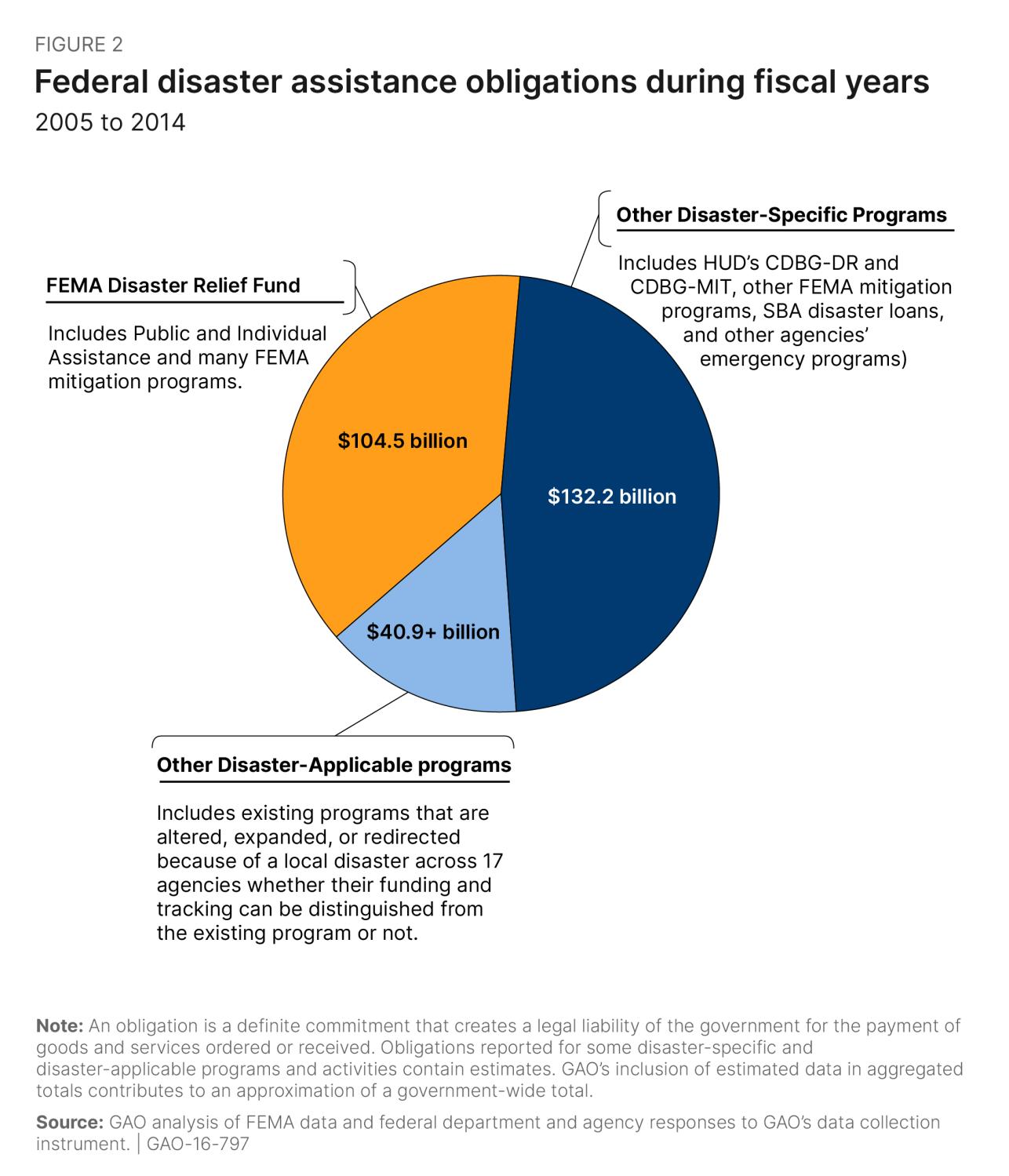

Take, for example, the National Disaster Recovery Framework (Figure 1). Congress funds this framework through a complex set of permanent, supplemental, and special budgets that include dollars for programs across multiple agencies that are not disaster-specific. For example, of the $121 billion in supplemental appropriations for Hurricane Katrina in 2005, FEMA spent only about $44 billion. The rest was spent through disaster-specific programs outside of FEMA, such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR). There are also programs that are not statutorily or budgetarily specific to disasters that have been used in disaster scenarios, such as Disaster Unemployment Assistance. Analysis by the Government Accountability Office found that funding for these programs has overshadowed FEMA funding (Figure 2).

There are many reasons for this complicated structure. First, each program’s remit is defined in statute, and incremental reforms and layering of processes have resulted in a behemoth of bureaucracy. For example, CDBG-DR is defined by the statutes associated with the 1974 CDBG program for urban development projects—not disaster recovery. The role and mission of each agency is defined by Congress, working through multiple legislative subcommittees that handle authorization, oversight, and appropriations. Generally, the programs were not defined with a holistic vision for federal disaster policy, let alone an integrated knowledge of the implementation challenges associated with each federal function relevant to disasters.

In some cases, this lack of coordination results in duplication. For example, CDBG for mitigation (CDBG-MIT) is a component of recent CDBG-DR appropriations that evolved from program set-asides after Hurricane Sandy in 2012. In 2018, HUD allocated $16 billion for mitigation infrastructure, buyouts, and related activities through CDBG-MIT. Yet Congress passed the Disaster Recovery Reform Act that same year, establishing the conceptually similar Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program in FEMA. So now there are two programs designed to perform essentially the same function, but with different funding streams, application processes, statutory limits, and program rules, and overseen and funded by different congressional committees.

This historically imbalanced development has produced programmatic siloes, yet our communities need these programs to work seamlessly. Each program attracts different applicants and has evolved its own rules and personnel based on its residing agency’s overarching mission, capacity, and appropriations. For example, in staffing, HUD’s focus on housing and community development has attracted planners, housing professionals, and social welfare specialists; meanwhile, FEMA has historically recruited from the first-responder community. Different skillsets can create inter-agency tension, and the institutional and professional management across them has become challenging, if not impossible.

There are many precedents for reorganizing federal disaster management

Several entities play important roles in monitoring federal disaster management and suggesting improvements, including the White House Office of Management and Budget, the Government Accountability Office, and each agency’s inspector general. But major reviews across the entire federal government are rare (except after milestone disasters such as Hurricane Katrina), and robust management reforms are few and far between.

The federal government’s role in disaster preparation and response is relatively new compared to its other roles and has evolved frequently—and in some cases, dramatically. Pre-World War II, the federal disaster apparatus was minimal. The passage of the 1950 Federal Civil Defense Act created a funding stream for state and local governments as well as the authorization of federal first responders, but without a formal federal organization. By the time President Jimmy Carter established FEMA in 1979, there were already over 100 distinct disaster management programs. President Carter’s reorganization brought together several programs previously housed in the Department of Defense, HUD, and the General Services Administration, and was codified further in the 1988 Stafford Act.

Since then, major emergencies have prompted further reforms. For example, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing led to the FEMA administrator’s placement in the presidential cabinet, and the September 11, 2001, attacks led to the creation of a new, consolidated super-agency (the Department of Homeland Security) with FEMA as a component. Due to the same incident, HUD also received a special congressional appropriation for its first CDBG-DR grants to rebuild Lower Manhattan.

This distribution of funds across the federal cabinet has exacerbated management gaps and delayed the weaving of a robust disaster safety net, with particularly significant challenges for the primary recipients of federal disaster aid: state and local governments. High-capacity state and local governments treat some federal funding streams as interchangeable, causing mission duplication and application burdens. Meanwhile, low-capacity jurisdictions are burdened by competing agency and program rules, and struggle to access support. Ultimately, federal services spur jockeying across local and state governments for limited resources, resulting in an inefficient and inequitable distribution of resources.

Immediately after Hurricane Katrina, challenges both within FEMA and across the federal government were widely documented in the media and debated within policy circles. A year later, Congress passed the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act to revise and expand FEMA’s jurisdiction and operations. This patchwork reorganization, with little to no interagency reform, continues today. The 2013 Sandy Recovery Improvement Act permitted more flexibility in FEMA’s Public Assistance Program for rebuilding larger-scale infrastructure, but left coordination gaps with other federal actors such as the Army Corps of Engineers and Department of Transportation. Similarly, the 2018 Disaster Recovery Reform Act—a response to 2017’s devasting hurricanes and wildfires—created FEMA’s BRIC program, but without any coordination of mitigation efforts with HUD on vital issues such as targeting social vulnerability or improving long-term resilience planning.

FEMA has been criticized both fairly and unfairly for the gaps in federal disaster management since the troubled Hurricane Katrina response and recovery. In truth, many agencies now house programs explicitly for disasters, and there are additional federal programs that will be altered by climate-related disaster events that should be integrated into disaster planning. However, the FEMA administrator is still the primary advisor to the president on all emergency matters, and—statutorily and in practice—FEMA is still the lead coordinating role in mitigation, relief, response, and, increasingly, resilience.

Over the last half-century, FEMA has learned lessons from tens of thousands of emergency and disaster declarations. But federal disaster management organization and operations have not always been consistent during that time, leading to poor knowledge management across the disparate programs.

Reform efforts have stalled while the disaster bureaucracy has increased

The current framework was laid out almost 50 years ago during wildly different environmental and social conditions than today. Over the last few decades, advocates and scholars have suggested a range of reforms that have made it into legislative proposals: reassigning agency roles, adding additional oversight agencies, and even overhauling the entire system.

In Hurricane Katrina’s aftermath, for example, there were calls to abolish FEMA, which had only recently been made a sub-cabinet-level component of the Department of Homeland Security after 9/11 . There have also been calls to move long-term recovery functions from FEMA and HUD to the National Security Council. Recent ideas center on creating a new entity to oversee federal disaster management, or establishing FEMA as a cabinet-level agency, which has received support both from scholars and practitioners, including FEMA’s own inspector general.

One group of proposals looks at appointing a disaster czar or a national chief resilience officer for mitigation, while another seeks the establishment of a coordinating oversight entity such as a disaster commission composed of expert scholars and practitioners (though a National Advisory Council already exists). These changes are meant to create a central clearinghouse overseeing the existing maze of programs across agencies, ostensibly coordinated under FEMA’s authority.

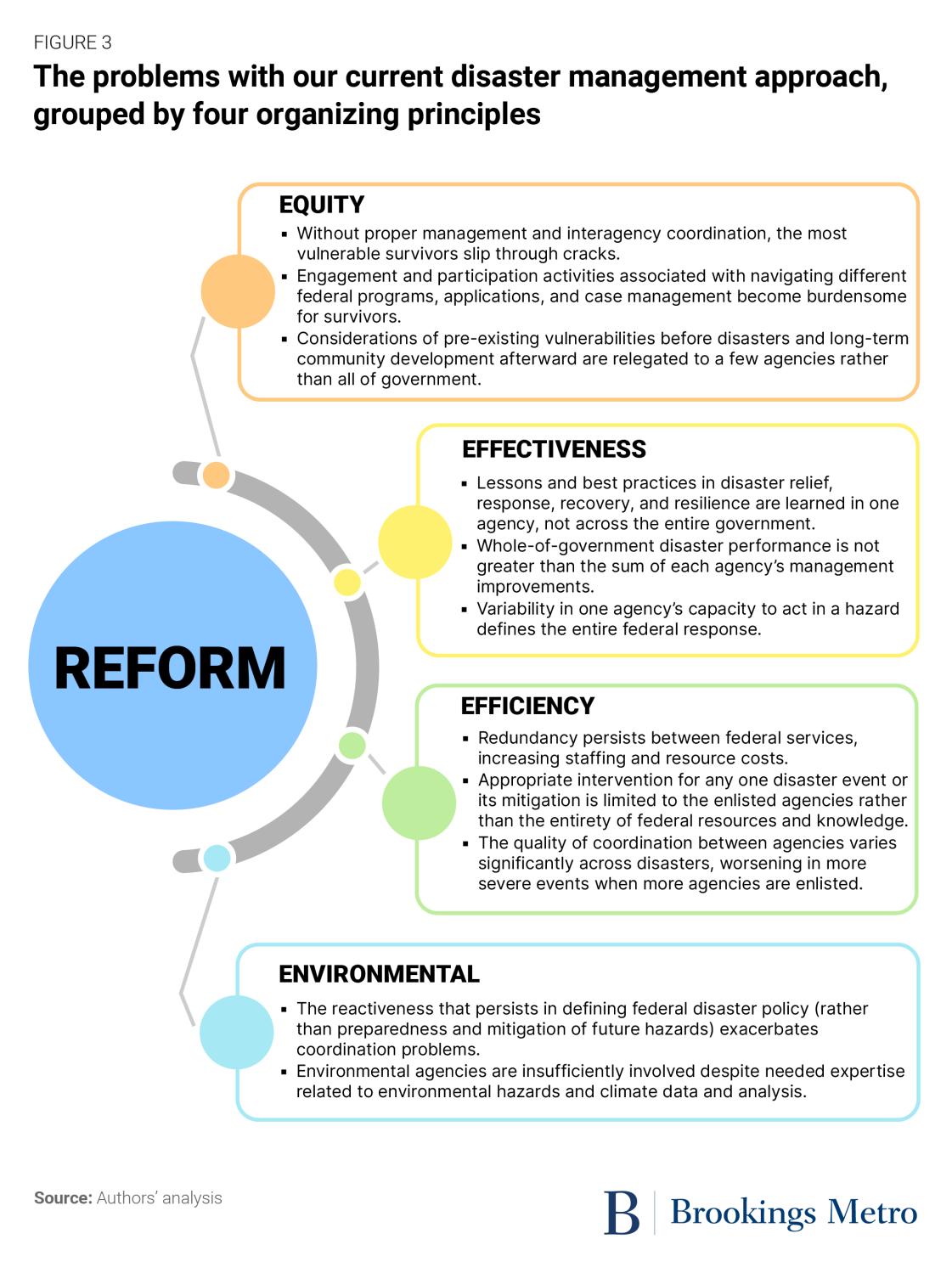

What’s clear is that the status quo is no longer tenable. The federal government’s historic approach—proliferating disaster aid programs and individual management tweaks within agencies, especially FEMA—needs to end. It is time to reform not just individual agencies but the entire disaster continuum. Figure 3 maps the current challenges against our four organizing principles to shed light on where and how to make change.

A principled reorganization can modernize and affirm federal disaster management

We should approach the question of reorganization with an eye toward centering survivor communities and households without bloating public bureaucracies, and in a way that reflects our changed environmental and social context.

Over the last decade, several efforts have analyzed the way siloes have perpetuated poor governance, especially in disaster and climate policy. We support the intent of governmental reform loosely known as “de-siloing”—however, creating a new silo has rarely been shown to de-silo. Consequently, adding an overarching czar or commission will likely not lead to better coordination, and building an entirely new disaster agency will lead to significant short-term challenges such as delays, further duplication, and confusion. Instead of a new czar or silo, we need a workable integration plan with a nimble integrator. Federal efforts in sectors such as homelessness provide preliminary models.

To start, we need a stronger—and better—FEMA. We need a FEMA with the personnel, budgets, and expanded authority to work comprehensively and cohesively to serve vulnerable populations beyond the hazard moment.

First, FEMA should be returned to its cabinet-level status while retaining the revised authority it received post-Katrina. Centering FEMA in disaster events should also extend to broader climate adaptation and pre-disaster housing mitigation activity. Just as improvements in FEMA damage assessments and reformed declaration processes jump-start the federal government apparatus after disasters, FEMA’s National Risk Index could be used to identify targeted exposures and vulnerabilities. When they hit an explicit threshold, they should trigger FEMA grant programs such as BRIC and the new Community Disaster Resilience Zones, while also enlisting the other federal resources and safety nets.

Second, some consolidation is necessary. Core disaster programs in other agencies should be reassigned to FEMA (especially duplicative ones such as CDBG-MIT), along with the staff and budgets. Merging duplicative efforts can streamline applications for frontline communities, but should be done without losing key differentiators, such as the CDBG-MIT’s focus on low- and moderate-income households. Consolidation ensures that all stages of the disaster continuum are more efficiently integrated and harmoniously serve local communities and survivors.

If done well, such integration could yield improved survivor experiences, more effective programs, and cost savings. But caution is necessary: If done poorly—such as failing to preserve flexibility and authority, or Congress failing to allocate the necessary personnel and budgets—the result could undermine our disaster safety net. Yet with careful policy reforms, this approach could pay dividends in our increasingly risky future.

Centralization does not eliminate the need for other agencies’ roles, particularly those involved in mitigation and resilience. A third reform, then, includes ensuring better strategic, mission, and planning coordination between FEMA and the “place-making” agencies that produce habitable and viable communities, such as HUD and the Department of Transportation. Their expertise is critical, but it needs to be better activated, applied, and integrated across the full disaster continuum. “Mission coordinators” should be employed across all agencies to align FEMA’s actions. These mission coordinators must participate in FEMA’s mitigation grant review panels and in respective agency competitive grant programs, while monitoring activities and outcomes from formula grants that may affect disaster exposures or events. These liaisons should also coordinate their agency’s local plans (such as HUD’s consolidated plans) with FEMA’s (e.g., hazard mitigation plans) for accuracy and comprehensiveness. FEMA’s regional administrators could also work with other agencies’ local representatives to better serve communities and track local development, utility and infrastructure quality, and other public actions that fall outside of federal authority.

Fourth, FEMA and the agencies that relinquish programs under these reforms should retain core operational staff for transitional functions and knowledge management, but also to better trigger and coordinate those agencies’ non-disaster safety net programs. Improved definitions and transparency about which disaster conditions trigger which programs can ensure those programs’ effectiveness. In HUD, for example, the operational coordinator would provide urgent data and planning knowledge in relation to a specific event or exposed place, while the mission coordinator ensures that FEMA-supported housing recovery reflects pre-disaster needs and supports local housing and development goals.

Fifth, standard safety net programs such as food and unemployment assistance that are put to use in disasters should remain in their host agencies, with expanded resources for coordination with FEMA. These programs can coordinate in ways that mirror county or city governments’ integration with operational coordinators as nodes between agencies. This reform, coupled with the changes above, means that survivors only knock on one federal door: FEMA, which then identifies the range of services and aid available to them. Pre-existing recipients of other agencies’ programs can use those as the entry point for other assistance. Improvements in FEMA’s processes for helping households would ease the burdens on those seeking support.

Sixth, FEMA must expand its first-responder mission, and Congress should inscribe this change statutorily. This new organization requires much more from FEMA than it currently delivers. FEMA should instill a culture of community resilience in its hiring and training, including a diversity of staff with community-level experience to shift its organizational culture from emergencies to resilience while maintaining its relief and response functions.

Finally, better management tools across the newly integrated disaster functions are needed. This includes investments in data technology and IT infrastructure, case management protocols, and long-term monitoring and evaluation. A reassignment of civilian defense and security funds to support the integration process—like under the 2006 Post-Katrina Act—could ensure the structure’s long-term cost effectiveness.

The U.S. could be a pioneer in reforming disaster management.

All countries have grappled with how best to manage their disaster assistance. In developed nations, this evolution has often manifested as a centralized and comprehensive emergency management agency (such as in Chile), a highly decentralized and fairly late creation of a national entity (New Zealand), or solutions in the middle (South Korea). The impact of global climate change and the transition to a majority-urbanized population necessitated these reforms in many nations. And though numerous factors determine disaster outcomes, there is preliminary evidence showing that some level of centralization and operational consolidation combined with mission-driven coordination leads to positive reductions in lost lives and damaged property.

In the U.S., the changing climate and national prioritization of vulnerable populations mean the time for a reorganization is now. In challenging FEMA to become a broader environmental and social support agency rather than solely an emergency response and relief authority, there is an opportunity to have a federal disaster management bureaucracy that is appropriate to our current needs.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The research included in this report was made possible through funding by the Walmart Foundation. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Walmart Foundation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).