This is the fourth post in a series on national disaster reforms. Previous posts outlined principles for reform, examined changes to the federal disaster declaration process, and recommended improvements in federal disaster management.

Disasters are economically costly. Many of these costs are well documented, such as the need to repair and replace damaged property, relocation expenses, and lost income or revenue for households and businesses. After a disaster, the public sector will have to rebuild or repair infrastructure and public buildings, and may lose tax revenue at the very moment they must also increase assistance to households. And with the increasing frequency, severity, and variety of climate-change-related disasters, these costs are only growing.

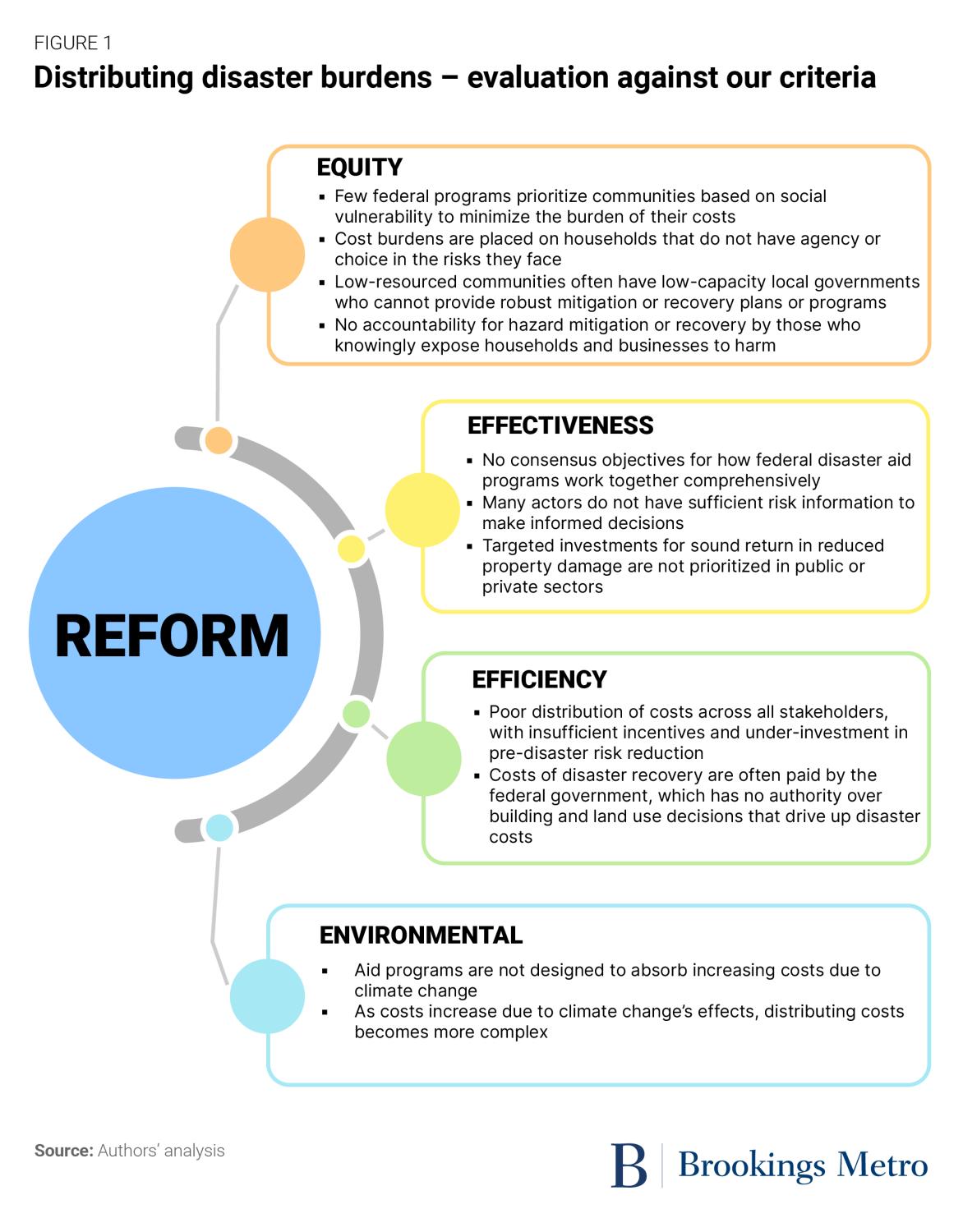

In this piece, we examine who pays which costs along the disaster continuum, including not just recovery, but also mitigation. Disasters are a shared burden and, as such, costs are inevitably spread across many actors. But the country’s current spending is missing opportunities to better align incentives, drive more cost-effective risk reduction, and more equitably distribute cost burdens.

Disaster reform should not remove all risk-sharing, as it reduces the costs for some of the most vulnerable and, if designed well, can increase the likelihood of risk reduction investments. Instead, we must better assign the cost of decisions that increase risk—such as developing on highly exposed land—to those who benefit from such decisions, including developers, their financiers, and political backers. We must also enable households and organizations to reduce their individual risk, especially populations facing higher costs due to historical disinvestment. But these strategies require us to document whose decisions are increasing risk and hold those stakeholders accountable.

So, where are we falling short in the current distribution of costs and allocation of responsibilities?

We lack an accurate understanding of the distribution of disaster costs

Comprehensive data on how disaster costs are distributed across stakeholders is lacking. The fact that disasters activate spending across multiple agencies at all scales of government makes tracking difficult, especially since most disaster spending is not explicitly marked as disaster-related dollars. Many public and private entities simply do not comprehensively track their spending on disasters. Collecting private sector spending on the full range of the disaster continuum would be an impossible task.

This is true for costs across the disaster continuum, which includes activities from before the event (mitigation and preparedness), during (relief and response), and after (recovery and reconstruction). And though all parties benefit from investments at every stage, costs are not evenly distributed.

While taxpayer dollars typically fund risk reduction, there are myriad private actors that benefit without contributing, from property and infrastructure developers to insurers. Further, our accounting frameworks—which keep disaster impacts and recovery as an incidental and unpredictable cost—make it difficult to capture the return on investment from risk reduction. Since we do not track disaster liabilities, reducing them is an expenditure, not a benefit.

Most disaster costs are federalized

With the federal government bearing many post-disaster costs, state and local governments may underinvest in risk reduction.

The federal government shoulders a substantial share of large disasters’ costs, though it has little influence, and no direct say, in policies such as building codes or local zoning. This cost burden is driven by the disaster declaration process as well as congressional choices about activating and funding other programs. When a declaration is issued, FEMA Public Assistance (PA) supports state, tribal, and local governments in clean-up, repairs, and rebuilding of public infrastructure. This can be quite generous, but typically comes with cost shares of 25% for the state or tribal government unless waived. Beyond PA grants, local governments are recipients of generous community disaster loans, repayment of which is often waived through loan forgiveness—essentially turning them, too, into grants. When activated, other programs direct even more dollars to local governments post-disaster. The Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program can funnel substantial dollars to local governments, as do programs in the Department of Transportation, Department of Commerce, and other agencies.

Local governments are not completely fiscally insulated. For example, research has documented that severe wildfires can have negative impacts on local budgets. Some states have annually funded disaster accounts or contingency budgets for certain agencies, and many will appropriate additional dollars or transfer funds between agencies post-disaster. Across the board, state and local governments pay a higher share of disaster costs for less severe events that do not exceed the federal declaration threshold. For all kinds of events, local governments also suffer longer-term losses in housing, economic activity, and other sources of revenue. Few of these costs are documented or analyzed across disasters. However, the federal government’s emergency response, recovery framework, and assistance programs are designed with significant redundancies—suggesting it can pay for a sizeable share of repairs and rebuilding after a disaster, including in communities that could have mitigated the damages.

When you dissociate the benefits and costs of an activity, it misaligns incentives. If disaster costs are paid by others, there is less incentive to pay to lower them, even when it would be cost-effective overall. Economists refer to this as “moral hazard.” Local and state governments make land use and building code decisions, and cities, counties, and special districts also directly fund and control much of our public infrastructure—even where federal agencies also provide funding. If those entities capture the benefits of risky choices—such as higher tax revenues and lower expenditures—but bear none of the disaster costs, excess development and underinvestment in hazard mitigation in high-risk areas will occur. Disasters will then wreak avoidable havoc—but evidence of contributions to that havoc are buried and accountability is elusive.

Under certain circumstances, moral hazard is less concerning; for example, when actors bear risk but do not have the ability to lower it. This could be because they lack decisionmaking power—take renters, who have limited ability to retrofit the homes they occupy. Some groups, such as low-income homeowners or nonprofits with little income and savings, simply do not have the funds to invest in reducing risks, even with the motivation and opportunity. Some jurisdictions have been so under-resourced (and some communities within them have been so underinvested) that disaster mitigation investments are well beyond their reach. Further, some elected officials overlook communities’ mitigation opportunities. And in some rural communities, there are insufficient resources for effective and fair disaster relief and response, let alone mitigation.

Federal assistance to households for disaster recovery is limited to prevent purported dependency

In larger disasters, households and businesses may get some assistance from the public sector, but they pay much of the costs themselves. Households often receive a lower share of total losses covered by federal support than local governments. The amount each household typically receives from FEMA’s Individual Assistance (IA) is limited: average grants for major storms range from only $1,000 to $8,000. The IA program can also be difficult for households to navigate, and has been shown to have administrative inequities.

Federal disaster loans to households and businesses will need to be repaid, limiting any federal subsidy to the interest rate. And while HUD dollars may ultimately make their way to households, it is uncertain and typically takes many years. This lack of immediate support for the most economically vulnerable can leave them struggling. Those with insurance fare better, but those without can spiral. This lopsided approach to disaster management is also inequitable: It traps under-resourced households and widens inequality post-disaster.

Our system prioritizes expensive recovery rather than prudent risk reduction

Community-level investments in risk reduction benefit all residents and, in turn, reduce public financial exposures. Given their scale, these investments are unlikely to be funded by any one actor, which underscores the need for public investment. Yet the public sector spends far less on risk reduction than on recovery, and it fails to target scarce risk reduction dollars to the highest-need and highest-risk areas.

Historically, investments in risk reduction have paled in comparison to spending on disaster recovery. FEMA’s pre-disaster mitigation spending has been minimal, and spending from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for flood mitigation has focused on a limited number of flood control projects around the country.

Recently, Congress has taken steps to reverse this trend by creating the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program in FEMA and the Community Development Block Grant Mitigation (CDBG-MIT) program, both of which prioritize risk reduction. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act put more funding into disaster mitigation programs, and a new state revolving loan fund was recently created through the STORM (Safeguarding Tomorrow through Ongoing Risk Mitigation) Act. While these federal dollars are substantial—with several billion for many of these programs—demand still outpaces available funding. In 2022, for instance, FEMA received BRIC funding requests that were four times greater than the amount available. As the risk of climate extremes rapidly evolves, ever greater funds will be needed to protect communities.

State and local governments—including special districts and utilities—hold more decisionmaking power on disaster mitigation investments than the federal government through routine public infrastructure updates, operation, and maintenance. Historically, local governments are the biggest funders of infrastructure, financed through municipal bonds and tax revenues. Municipal and county governments also have control over the nature of local land development that may affect hazard exposure; for example, allowing development close to forested areas at risk of wildfires or along threatened coastlines. While increasing climate risk poses new challenges to local governments’ capacity to respond, they have a wide range of resources available now to engage in proactive (and sometimes expensive) infrastructure investments to reduce these risks.

The benefits of risk reduction actions and their scale call for governmental coordination and investment that account for and are supported by various local actors across sectors. Yet questions remain regarding which level of government is responsible for those costs across our federalist system. With highly localized benefits, there is logic to local governments (and their taxpayers) being the leading providers of hazard mitigation and climate adaptation investments. That said, many may not have sufficient resources, which requires federal or state assistance that is better targeted toward disadvantaged communities, such as is proposed under the Justice40 Initiative.

We lack clear and consistent information on evolving climate risks or the engineering innovations that can mitigate them

Without greater transparency on risks and mitigation, optimal decisions for distributing costs—and especially, making the best investments in risk reduction—are difficult to make. Individual private actors such as scholars, real estate brokers, or insurers often have proprietary information on risks at a fine scale that is not available to the average household or to under-resourced communities. But even then, their information typically does not comprehensively include the range of risks across all disaster types and how they are evolving for any one property.

Households and businesses must make decisions about where to locate and how to invest in making their homes better able to withstand increasingly costly natural disasters. Local and state governments make decisions about land use and building codes. None of these decisions will be optimal without full and transparent information on the risks and how they are changing in the near and medium term. The lack of clear and understandable risk communication can influence perceptions of costs and benefits and create information asymmetries that disadvantage lower-resourced communities.

Recommendations for better distributing the cost of disasters

Given the challenges outlined above, there are several ways that policymakers and stakeholders can reform pre- and post-disaster efforts to distribute the costs more evenly across groups and governments.

Adopt a state deductible for federal public assistance

The federal government’s assumption of many disaster costs may lead to less state action to reduce disaster risks, such as through improved land use and stronger building codes. During the Obama administration, FEMA proposed establishing a “deductible” for states under the PA program; states could lower their deductible by adopting hazard mitigation practices, or it could be adjusted to account for prevailing financial resources in the impacted localities and indexed to the frequency, magnitude, and exposure of hazards. States would spend up to their deductible on disaster costs before the federal government would intervene. This proposal would have made cost burdens transparent to local governments and better aligned incentives, rewarding states that lowered their losses instead of those that did nothing. It would also have improved efficiency by saving on administrative costs for smaller declarations. Though it was never enacted, FEMA has noted that such a program would improve parity in the funding amount sub-national governments receive, and it deserves reconsideration.

Expand the mitigation requirements of disaster aid programs to state and local governments and, where fair, to households and private entities as well

Currently, FEMA has few requirements for pre-disaster risk management tied to post-disaster aid. Recipients of aid must only maintain disaster insurance, and their states must have adopted an enhanced mitigation plan to unlock additional Hazard Mitigation Grant Program dollars. Congress should request a study across the range of federal rebuilding and recovery programs to determine what, if any, additional pre-disaster risk reduction requirements should be tied to receipt of post-disaster funds. Such actions could include required hazard assessments for new development permits in coastal areas subject to sea-level rise or in the wildfire-urban interface, and updated state requirements for property risk disclosure. As discussed previously, a sliding scale for disaster declarations could allow for greater federal involvement, and be tied to greater action on risk reduction.

Direct disaster rebuilding, recovery, and mitigation dollars to those most in need

Currently, many federal post-disaster programs do not target dollars to those most in need of financial assistance, nor do they provide comprehensive assistance to keep households from spiraling into insecurity. Prioritizing recovery dollars to those with the most socioeconomic need would help address inequities in disaster recovery. Doing the same for mitigation opportunities such as buyouts and fireproofing would also reduce the recovery costs for under-resourced household and communities as well as the government. These recipients are also less likely to engage in excessive risk-taking even if they are benefiting from greater federal post-disaster assistance, since they often lack the needed resources to reduce risks ex ante. This would involve adopting a means-tested assistance program for the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), directing IA and PA more frequently and in higher amounts to lower-income households and local governments, prioritizing under-resourced areas for hazard mitigation investments, and limiting cost-share waivers to frontline communities.

Improve public information so all stakeholders understand their risks and the post-disaster resources available to them

Optimal disaster risk management decisions cannot be made without an understanding of the risks themselves, their impact, and what post-disaster resources are available. Yet many material and financial aspects of disaster risk are opaque. Potential policy reforms include updating FEMA flood maps to show gradations of flood risk, producing comprehensive and free national climate risk maps, and creating an accessible online tool to look up NFIP premiums as well as prior floods and related damages for households and communities. But there must also be a federal commitment to ameliorate informational asymmetries via public, rigorously collected exposure data for all hazards, and make that information easily accessible for households and property intermediaries irrespective of background. Educational campaigns in predominately low-income or underserved communities can ensure everyone has access to risk information. We should also hold the public and private institutions that gatekeep information about risk accountable—unlocking the information for decisionmakers such as regulators, state agencies, and private firms in land development and insurance.

Incorporate changing risks into public sector decisionmaking

Public sector decisions beyond those focused on disasters should still consider disaster risks and how they are evolving. Most public investments in communities are designed to make them economically, socially, and environmentally viable for the immediate future. But if we do not account for growing risk, we put more post-disaster fiscal strain on taxpayers. Direct federal transfers for programs that support development and investment—such as through the Department of Transportation, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Environmental Protection Agency, for example—should include requirements for risk assessment over the life of the funded investment. Similarly, direct assistance to households—such as through mortgage securitization and other consumer financing programs—should consider property-level risks and how they are changing. Where exposure make investments unviable, transition plans should connect to longer-term relocation and resettlement. In this way, individuals and governments may avoid financial shocks and disaster damages.

Increase transparency about decisionmaking processes to hold all actors politically accountable and financially liable

Many of the places and properties we occupy were built when risks were unknown or much lower. Today, climatological, geological, and hydrological data is more precise and accurate. Current and future risks are better understood, and contributors to increasing exposures are more easily identified. Despite that, many decisionmakers continue supporting land development, infrastructure expansion, and related economic activities that put people in harm’s way. Other actors, such as private insurers, would benefit from more expansive risk reduction, yet they rarely contribute to such investments. The chain of decisionmakers—from mortgage lenders down to individual families—assume the original approvals for land development were done in good faith. But this is not always the case. Private sector interests and government officials should be held accountable for the higher disaster recovery costs and mitigating the risks to lives and livelihoods.

We need to rethink the distribution of the costs of disaster recovery and mitigation

Our current distribution of disaster costs and benefits is decades old. By rethinking how these costs are shared across many actors and sectors, we can incentivize better choices, improve cost-effectiveness, and ensure greater equity and transparency.

Ultimately, questioning who is accountable for disaster losses may lead to broader questions on the responsibility of high-carbon emitters for climate-driven damages. Such questions are deserving of more policy consideration and research. In the meantime, we can build a modern public and private system for disaster funding and investments that encourages individuals and communities to invest in themselves and provides a helping hand where needed.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The research included in this report was made possible through funding by the Walmart Foundation. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Walmart Foundation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).