A perennial topic for discussion at the Munich Security Conference is the American insistence that Europe spend more on its own defense. For the past several years, that’s been connected to a pledge made by NATO members at their 2006 Riga Summit to move toward spending 2 percent of GDP on defense.

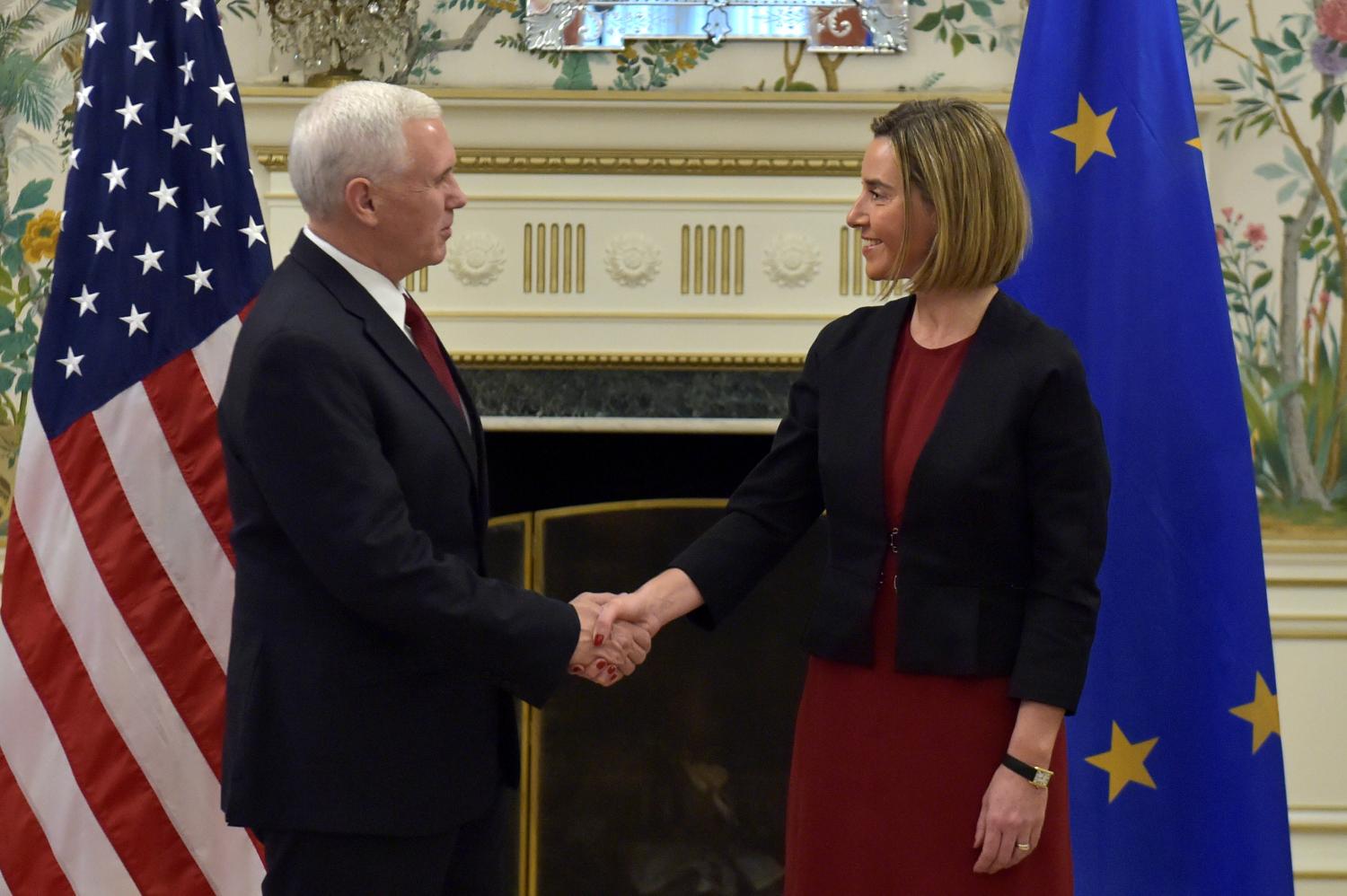

The 2 percent figure has taken on totemic significance in U.S.-European debates. The latest American political figure to invoke it is Donald Trump, who in an interview with the German press singled out the handful of European states that meet that target and castigated those that don’t. He warned that the American commitment to NATO and European security would be called into doubt if Europe didn’t spend more. As I wrote in a previous dispatch, in their Munich speeches Defense Secretary James Mattis and Vice President Mike Pence offered different formulations for the relationship between spending and American commitment, but 2 percent was there nonetheless.

If the American invocation was predictable, so was the European response: We agreed we should spend more; we are spending more; we might spend more; the issue is really about efficiency. Just as the United States seemed to have three positions on the NATO question, so too did Europe’s most important economy, Germany. Its chancellor, finance minister, and defense minister each took slightly different positions on the issue over the course of the three-day conference.

[M]any of the threats that Europe faces—from Russian political/news manipulation to destabilizing refugee flows to domestic radicalization—are ones for which NATO is not well suited to respond. NATO is first and foremost a tool for territorial defense.

The whole conversation rather completely misses the point. First, as many others have pointed out, spending 2 percent—as Greece does, for example—hardly guarantees that NATO members will have an effective military structure or be willing to use it. Second, many of the threats that Europe faces—from Russian political/news manipulation to destabilizing refugee flows to domestic radicalization—are ones for which NATO is not well suited to respond. NATO is first and foremost a tool for territorial defense. While Russian actions in Ukraine and pressure in northeastern Europe highlight that this remains, unfortunately, a vital necessity, Europe is being undermined from within more effectively than it’s being challenged from without.

As for the question of burden-sharing per se, I’m rather more sympathetic than many in D.C. to the notion that this balance should shift decisively. Looking at the world from Washington, there are the following realities: In the Pacific, the $12 trillion entity that is modern China is flexing its muscles, and the American presence is still the only potential source of stability in an otherwise volatile Asia. Even with our $18 trillion economy, meeting the challenge of stability in Asia will be a heavy drain on American resources.

Then there’s Russia—a $1 trillion entity; smaller than Italy, smaller than Spain, a third the size of Britain, a quarter of the size of Germany or France. Can the $17 trillion entity that is Europe not handle the basic defense—security, political, informational—of its own territory, versus whatever threat Russia actually poses? That can mean NATO, that can mean the EU, that can mean effective European strategy—the tool is not the point. The United States has a huge stake in the outcomes in Europe and continuing to shoulder an important part of the burden is logical—and especially necessary in the nuclear realm—but in support of, not substitution for, a credible European security architecture.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Two cents on the 2 percent question

A dispatch from the Munich Security Conference

February 21, 2017