Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, there has been a surge in exports from around the world to countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus. This export boom is so large that it cannot conceivably be targeting domestic demand in these countries. Admittedly, the evidence is circumstantial, but it seems highly likely that this export boom reflects transshipment of goods to Russia. We use the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) direction of trade data to show just how massive these transshipments are. Countries in the European Union—especially Germany and Italy—are the main drivers of this transshipment trade among advanced economies, while Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States have seen less of an export spike. Compared to the size of total exports, these transshipments are a rounding error for Germany and Italy. There is little reason therefore to think that prohibiting this trade would have material adverse repercussions on either country, while these goods may be disproportionately important for Russia.

The EU export surge to Central Asia and the Caucasus

The IMF direction of trade database consists of monthly data on pairwise trade between essentially all countries around the world. These data make it possible to track, for example, German exports to the Central Asian country of Kyrgyzstan and—conversely—what Kyrgyzstan reports as imports from Germany, i.e., the mirror image of German export data. These data are in millions of U.S. dollars, i.e., they describe values not volumes. These data may thus overstate the rise in transshipment volumes if Western export controls cause the price of transshipped goods to rise. Given how large the rise in export values is, however, we see this effect as second order.

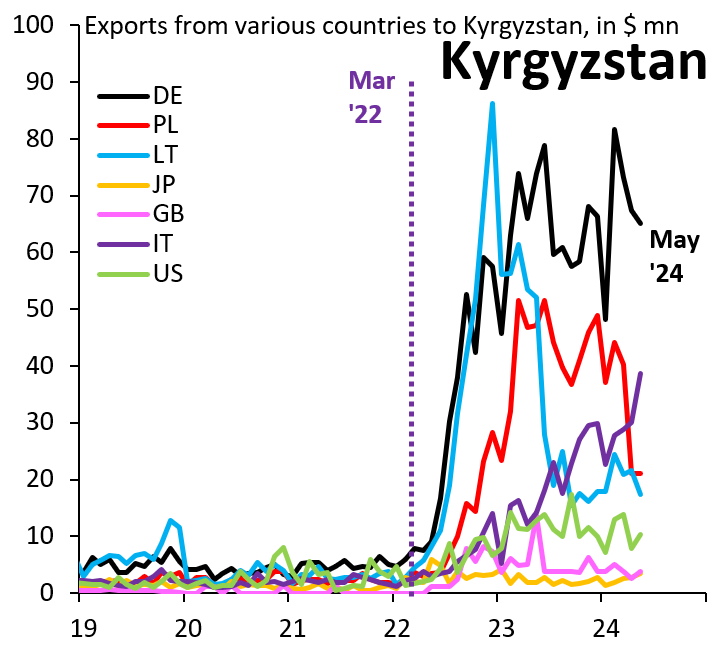

Figure 1. Exports from various countries to Kyrgyzstan, in millions of dollars

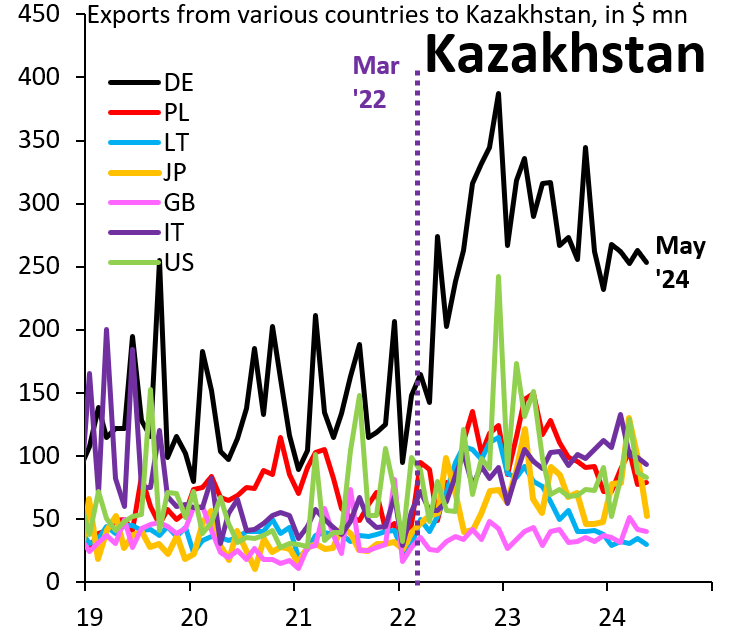

Figure 2. Exports from various countries to Kazakhstan, in millions of dollars

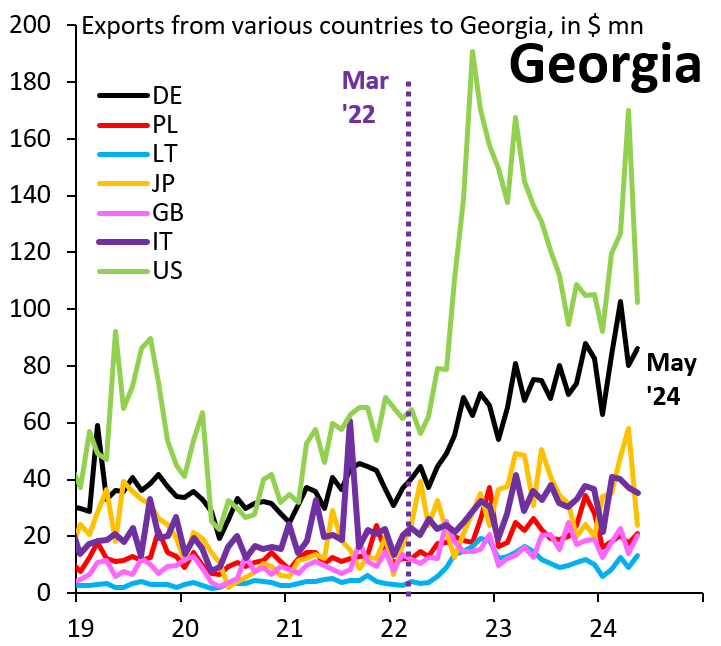

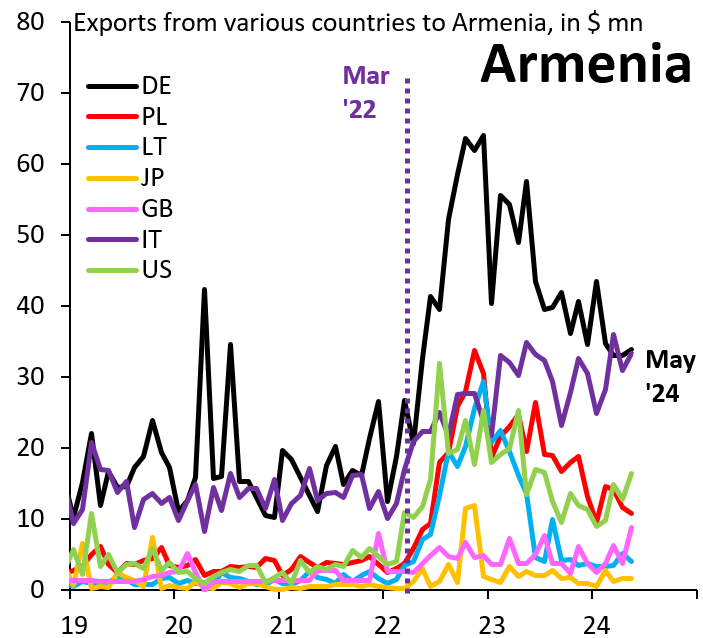

We track exports from Germany (DE), Italy (IT), Japan (JP), Lithuania (LT), Poland (PL), the U.K. (GB), and the U.S. to four countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Kyrgyzstan (Figure 1), Kazakhstan (Figure 2), Georgia (Figure 3), and Armenia (Figure 4). Exports start to rise sharply immediately after Russia invaded Ukraine and the imposition of Western export controls, strong circumstantial evidence that these goods are really going to Russia. This export surge is most pronounced for countries in the EU, where it is led—at this point—by Germany (black) and Italy (purple). Exports from Japan (orange), the U.K. (pink), and the U.S. (green) rise much less, though the U.S. has seen a spike in exports to Georgia. The export surge so evident in these charts generalizes broadly, including to China and Turkey, which—outside of the West—are by far the biggest source of transshipments to Russia. While the pairwise magnitudes are in many cases small—even after the sharp post-invasion rise in trade—the fact that practically every country in the world has surged its exports to Central Asia and the Caucasus means that these transshipments are large in aggregate. We estimate they offset at least half the drop in direct exports from Western countries to Russia.

Figure 3. Exports from various countries to Georgia, in millions of dollars

Figure 4. Exports from various countries to Armenia, in millions of dollars

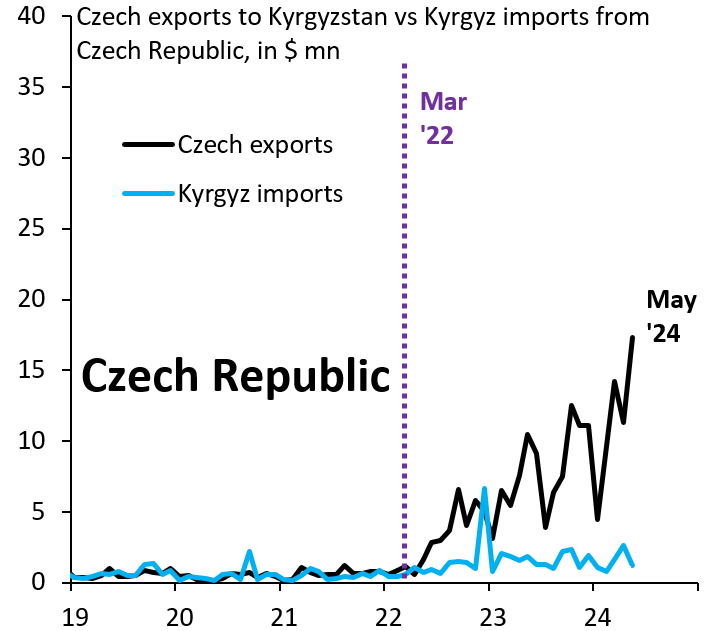

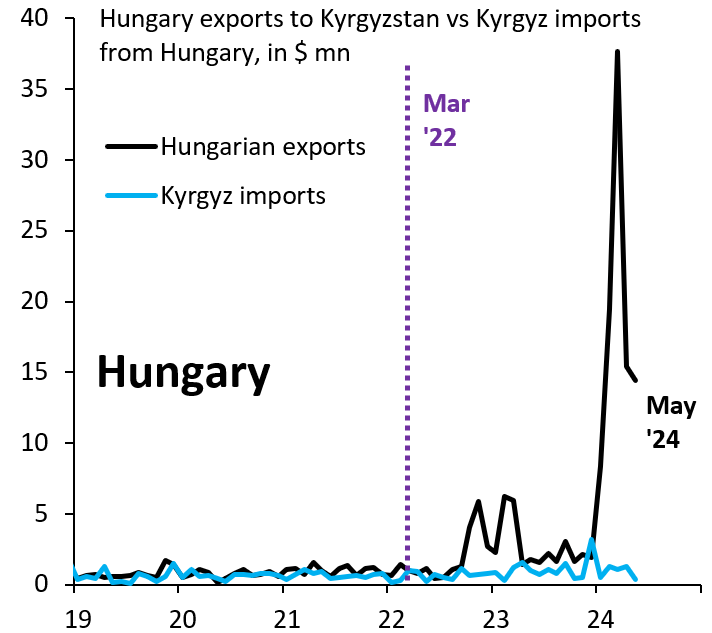

One telltale sign of transshipment is that a country like Germany will report exports far above what Kyrgyzstan reports as imports coming from Germany. This kind of divergence suggests that exporters in Germany invoice goods as going to Kyrgyzstan, where they never actually show up. Figures 5 and 6 show how important this “false invoicing” phenomenon is for Czech and Hungarian exports, respectively. The post-invasion surge in exports never arrives in Kyrgyzstan and—most likely—goes directly to Russia. False invoicing is very widespread, so that the Czech and Hungarian data can be thought of as representative examples.

Figure 5. Czech exports to Kyrgyzstan vs. Kyrgyz imports from the Czech Republic, in millions of dollars

Figure 6. Hungarian exports to Kyrgyzstan vs. Kyrgyz imports from Hungary, in millions of dollars

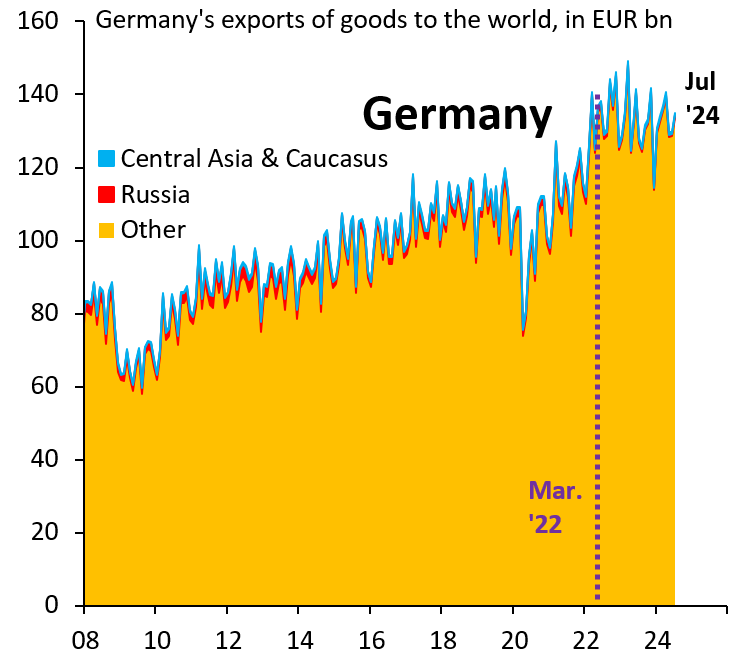

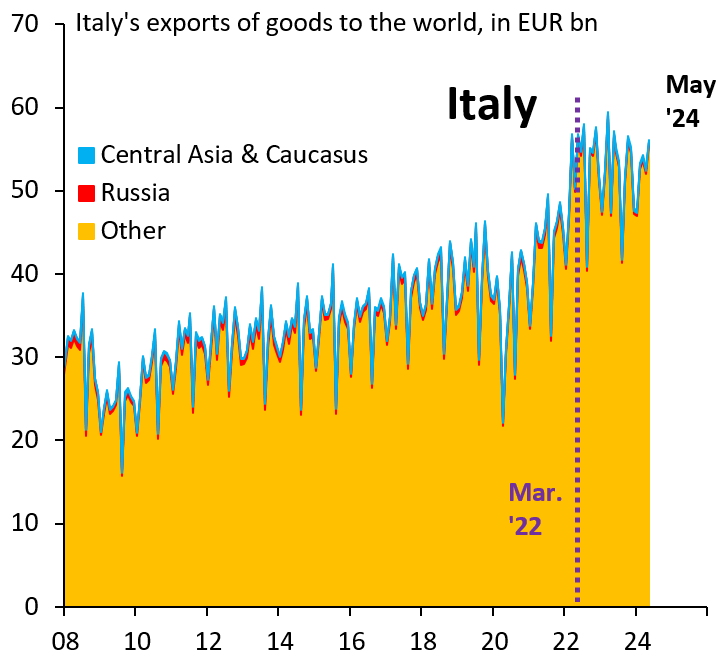

German and Italian export exposure is small

A common defense for these transshipments is that German and Italian manufacturing, for example, depend on Russia as an important export destination. This is not the case. Exports to Russia as well as Central Asia and the Caucasus are a rounding error for the German and Italian export machines, as Figures 7 and 8 show. Prohibiting these exports is therefore unlikely to have a material adverse effect on growth in Germany or Italy, while these goods may be disproportionally important for Russia. Our next blog post will show that the bulk of these transshipments consists of motor vehicles and parts as well as machinery and tools. While these goods may not fall under Western export controls, they almost certainly fall into the dual-use category.

Figure 7. Germany’s exports of goods to the world, in billions of euros

Figure 7. Italy’s exports of goods to the world, in billions of euros

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Transshipments from the EU to Russia

September 12, 2024