As students return to classrooms this fall, COVID-19 continues to present schools across the country with challenging circumstances. The pandemic has already impacted learning on an unprecedented scale, exposing and magnifying deep inequities within our education system. While no one has been left unscathed, the impacts have been most severe for those who were already the furthest behind academically—students of color and those experiencing poverty.

In the coming school year and beyond, data on student progress will be critical to understanding the disproportionate impact of the pandemic and addressing the resulting inequities. While learning has suffered across the board, the data tell a nuanced story. Understanding those nuances—particularly at the state and local level—will be essential to targeting evidence-based interventions (and recovery resources) to the students who need them most.

The research team at NWEA has been working diligently throughout the pandemic to analyze data from the MAP Growth assessment to illuminate the effects of COVID-19 on student growth and achievement. Even amid very challenging circumstances, students made modest gains in reading and math in 2020-21. We also see, however, that students experienced slower growth rates and lower achievement levels, on average, in both math and reading in 2020-21 compared to a more “typical” year (the 2018-19 school year). More specifically, students ended the year with reading achievement levels between 3 and 6 percentile points behind and 8 to 12 points behind in math.

The impacts of the pandemic were even larger among students of color and students experiencing poverty, especially in the youngest grades we studied. For example, Latino third graders showed declines of 17 points in math and 10 points in reading compared to historic averages. Black third graders ended the 2020-21 school year 15 points lower in math and 17 points lower in reading.

Figure 1: MAP Growth achievement percentile rank difference by cohort and race/ethnicity for reading and math

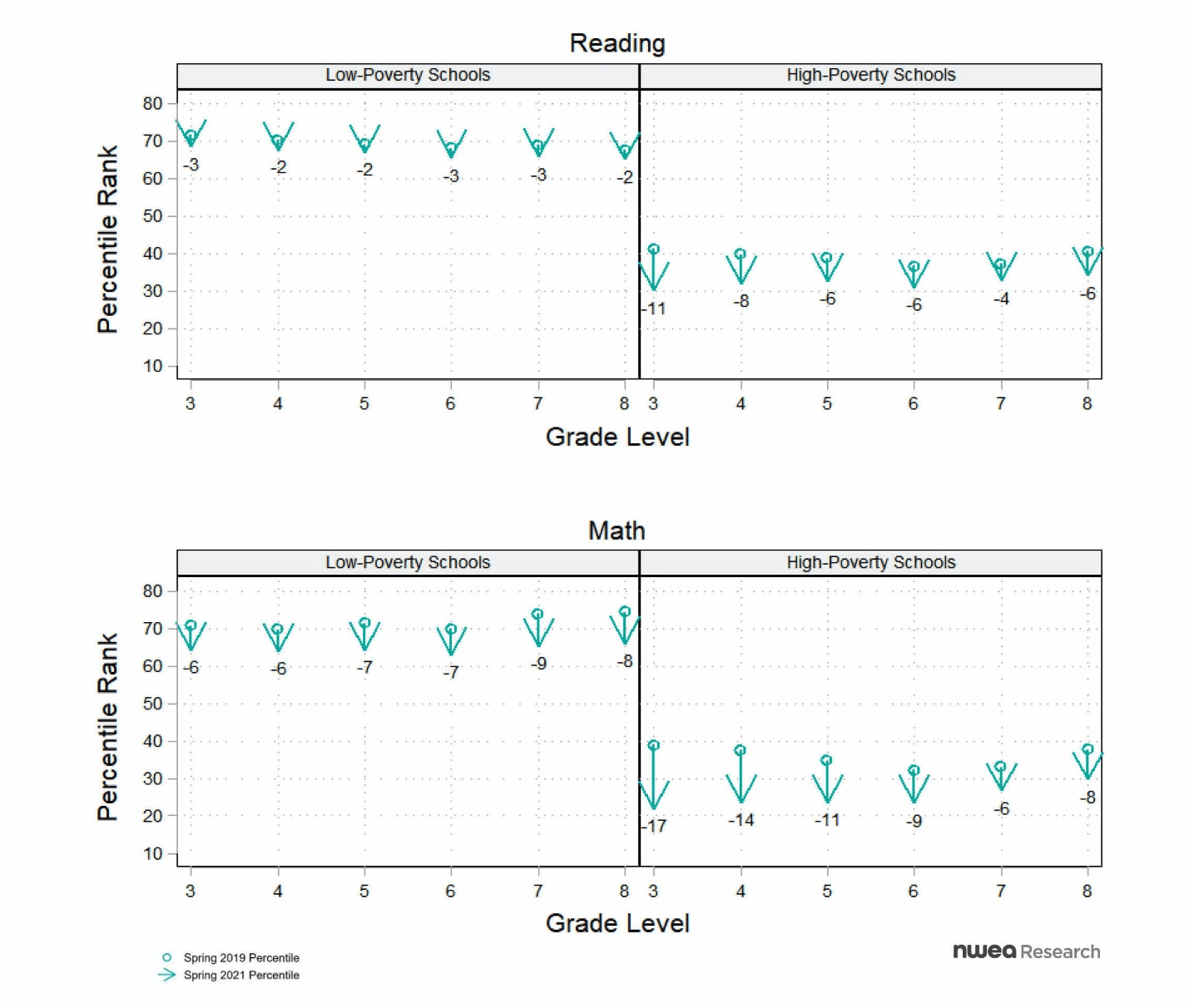

We found declines of a similar magnitude for students in high-poverty schools, where students in the earlier grades again saw the largest setbacks. For instance, third and fourth graders in high-poverty schools experienced declines in math achievement of 17 and 14 points, respectively, compared to a typical year.

Figure 2: MAP Growth achievement percentile rank difference by cohort and school poverty level for reading and math

Our education system is facing an unprecedented crisis. Despite the challenges, however, there is reason for optimism. With the near-universal return of in-person instruction and significant federal funding to deploy, education leaders have an opportunity to develop a strong foundation for equitable and excellent education for all students. Short-term recovery efforts can lead to long-term transformation if states and districts invest resources in evidence-based, holistic strategies, particularly those that have been proven to accelerate learning for historically underserved students.

More specifically, we believe that education leaders should:

- Re-engage disconnected students. Our data shows that the pandemic has impacted learning unevenly and on an unprecedented scale. Estimates suggest that as many as 3 million students across the country went “missing” from schools last year. This missingness is apparent in our data as well. We find overall attrition rates were higher than normal, which is to be expected given the challenges of the past year. We see even higher attrition rates for students of color, which means the true impacts of the pandemic on academic achievement may be even more dire that what we report. This underscores the need for states and districts to make extraordinary efforts to identify disconnected students, reconnect them to their school communities, and provide them with the support and interventions they need to access grade-level content while recovering lost ground.

- Expand instructional time. NWEA data shows that all student groups learned at a slower rate and ended the past school year with achievement below their same-grade peers in previous years. The disruption in instruction—particularly the reduction in structured learning time for many students—was surely part of the problem. In response, states and districts should consider expanding instructional time and opportunities for learning in evidence-based ways that have shown to improve outcomes for historically underserved students, such as through small-group tutoring and mentoring.

- Support access to remote learning technology for students and families. Before the pandemic, the “homework gap” left nearly 17 million children offline. That includes about one in three Black, Latino, and Native households—compared to about 20% of white households—and almost half of families making less than $25,000 per year. With instruction, extracurricular activities, and family engagement likely to continue to happen online (in some form) well into the future, it is essential to support the technological needs of students and families (e.g. access to high-speed internet and devices, as well as digital literacy).

- Attend to physical, social, and mental health needs of students. As the pandemic continues, students and families need support addressing basic needs and coping with everything from anxiety to trauma arising from major life disruptions. Evidence shows that students are unable to reach their academic potential without socioemotional and mental health support. States and districts should make mental health services available in schools, including increasing access to school nurses and counseling services. They can also partner with community organizations to support underserved families.

- Measure student progress and use data to advance learning. To understand the uneven impacts of the pandemic and inform effective recovery, it is essential that educators and school leaders have ongoing and high-quality data on multiple dimensions of student progress. Interventions should be targeted at students whose learning has suffered disproportionately and continuously adjusted to reflect evidence on what’s working, particularly for historically underserved students.

The pandemic has had the most dramatic impact on the learning of those students who could least afford to fall further behind. As a result, equity is the most important lens through which we must evaluate efficacy of educational investments and the success of recovery efforts. The impacts of COVID-19 will last far longer than the federal recovery funds. Thus, states and districts must look beyond short-term fixes and deploy resources to catalyze transformation that can last a generation. America’s children are counting on it.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).