In Paris there is new hope that negotiators can actually draft a global climate change agreement to reduce global greenhouse gases. But back here in the United States there’s nothing new at all. Regardless of what emerges from Paris climate policy will not change much in the near term. President Obama returns to a political world that is completely divided on the topic and a public that is divided, lukewarm and largely indifferent.

The Republican opposition to climate change legislation is not new. In the past decade the climate deniers have found a comfortable home in the Republican Party and even though there are signs that some Republican leaders are moving toward accepting the reality of climate change they all remain steadfastly opposed to any action on it. Even as the Paris conference began, the Republican Majority Whip, Congressman Kevin McCarthy, announced that he would not pay for any climate change treaty.

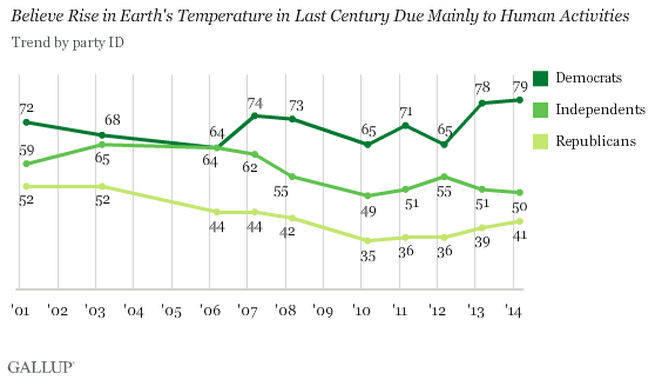

The following chart from Gallup shows just how partisan the issue has become since 2001.

In addition to Republican opposition, public indifference serves as another hurdle for officials interested in doing something on climate change. Just a few years ago—in the summer of 2010—a significant climate change bill, dubbed “cap and trade” bit the dust—even though Democrats held both houses of Congress and the White House.

So how do we get climate change politics back on track in time to be part of any deal that comes out of Paris? Unpacking and understanding the public’s indifference on the topic is the first step.

Below are a few insights gleaned from public opinion.

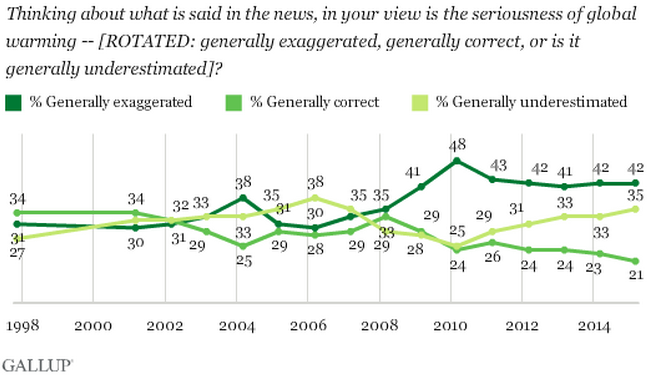

1) Even though news about the shrinking polar ice cap or the disappearance of several island nations is broadcast with some regularity, a big chunk of the public doesn’t take the media reports very seriously. For instance, since the turn of the century Gallup has been asking the public’s opinion of news reports about global warming and, as the Figure #1 below indicates, a growing number of people think those news reports are exaggerated.

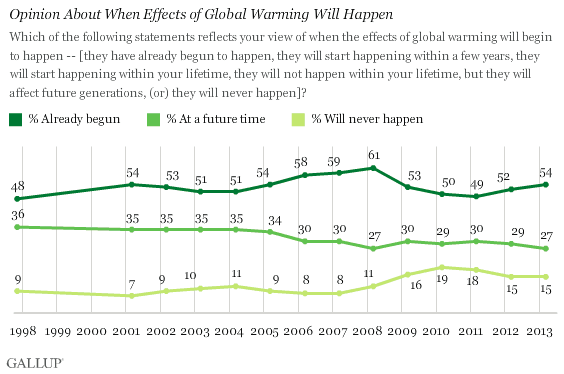

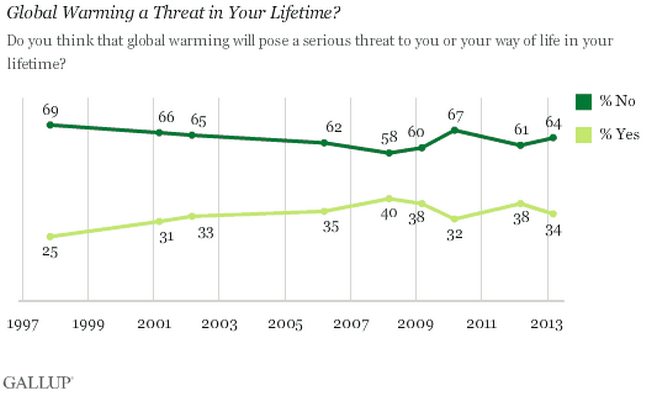

2) Although most people think the effects of global warming have already begun they are not very worried about them (see the following figures). More than half the public thinks that global warming is not something that will pose a serious threat in their lifetime. Rhetoric about leaving the world a better place for one’s children and grandchildren is nice but as a political proposition asking people to sacrifice today for benefits that may accrue once they are gone is tough—not impossible—but tough. When pollsters ask Americans in open-ended questions, to list the issues they care about, climate change is often in single digits—and frequently fails to make the top ten.

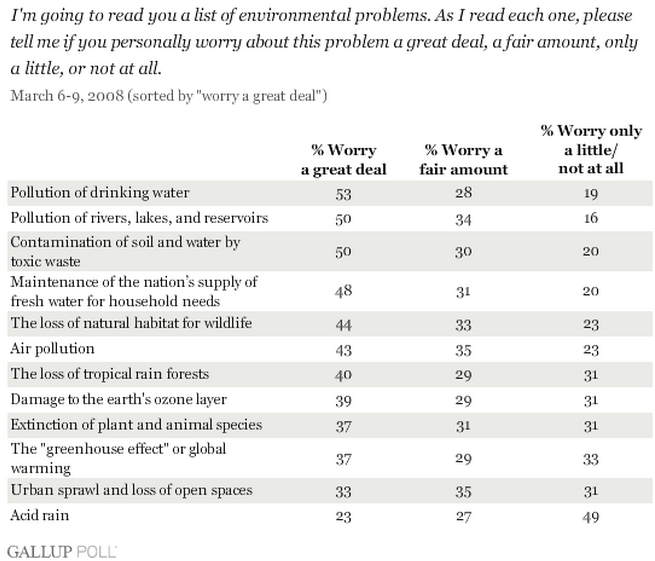

3) Back in the 1960s and 1970s the first chapter of the environmental movement unfolded. The focus of that movement was things that people could see, taste and smell. Dead birds in suburban back yards as a result of pesticides. Rivers covered in sludge that caught fire they were so polluted. High rates of cancer and birth defects from chemical plants. No abstract thought is needed to become enraged and demand action from things that normal people can see. It’s easier to convince people of the need for change when the enemy they fear affects them today. No wonder these are at the top of the list of a 2008 poll by Gallup that asked people what they worried a great deal about. Note that in the following chart, as the issues get more abstract and less “visible” the worry decreases. Global warming is much more of an abstraction than dirty water coming out of your tap. It takes some educating to put together the temperature rise, the ice caps melting, the seas rising and the resulting dramatic weather events. No wonder that in many polls a high point in public consciousness on global warming takes place around 2006 and 2007 when Al Gore’s movie “An Inconvenient Truth” was being shown and talked about—a time before the recession moved everyone’s mind to their pocketbooks.

4) And finally there’s what I call the Cuyahoga River effect. In 1969 the Cuyahoga river, which runs through Cleveland, was so polluted with industrial waste that it caught fire on a Sunday morning in June near the Republic Steel Mill. This wasn’t the first time the river caught fire but it was the first time that the fire caught the imagination of the entire nation and focused attention on water pollution. Efforts to clean it up had begun before the fire and intensified afterwards. Forty plus years later, the river is home to more than 60 species of fish and the fire is an important inflection point in the history of the environmental movement. We have “fixed” other environmental problems as well. Remember acid rain? If it appears in the news at all these days it’s vis-a-vis China—not Ohio. But have our environmental successes lulled the public into a false sense of security on climate change? Can we really “fix” this one too without immediate action?

Climate change is perhaps the toughest public policy challenge ever—mostly because it lacks immediacy. Even as more and more people come to accept the science behind it, climate change is still a distant threat. Making good on any agreement that will come out of Paris will need more than Republican support. It will need for the public to see this as today’s not tomorrow’s problem. It will need the functional equivalent of the fire in the Cuyahoga river.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The real enemy to progress on climate change is public indifference

December 3, 2015