The Federal Reserve substantially expanded its portfolio, or balance sheet, during and after the Great Recession. Although the Fed has since shrunk its balance sheet, it has decided to hold a much bigger portfolio of bonds than it did before the Great Recession. As a result, the way in which the Fed influences short-term interest rates now is quite different than it was before 2008. Here’s how.

What is the Fed’s balance sheet?

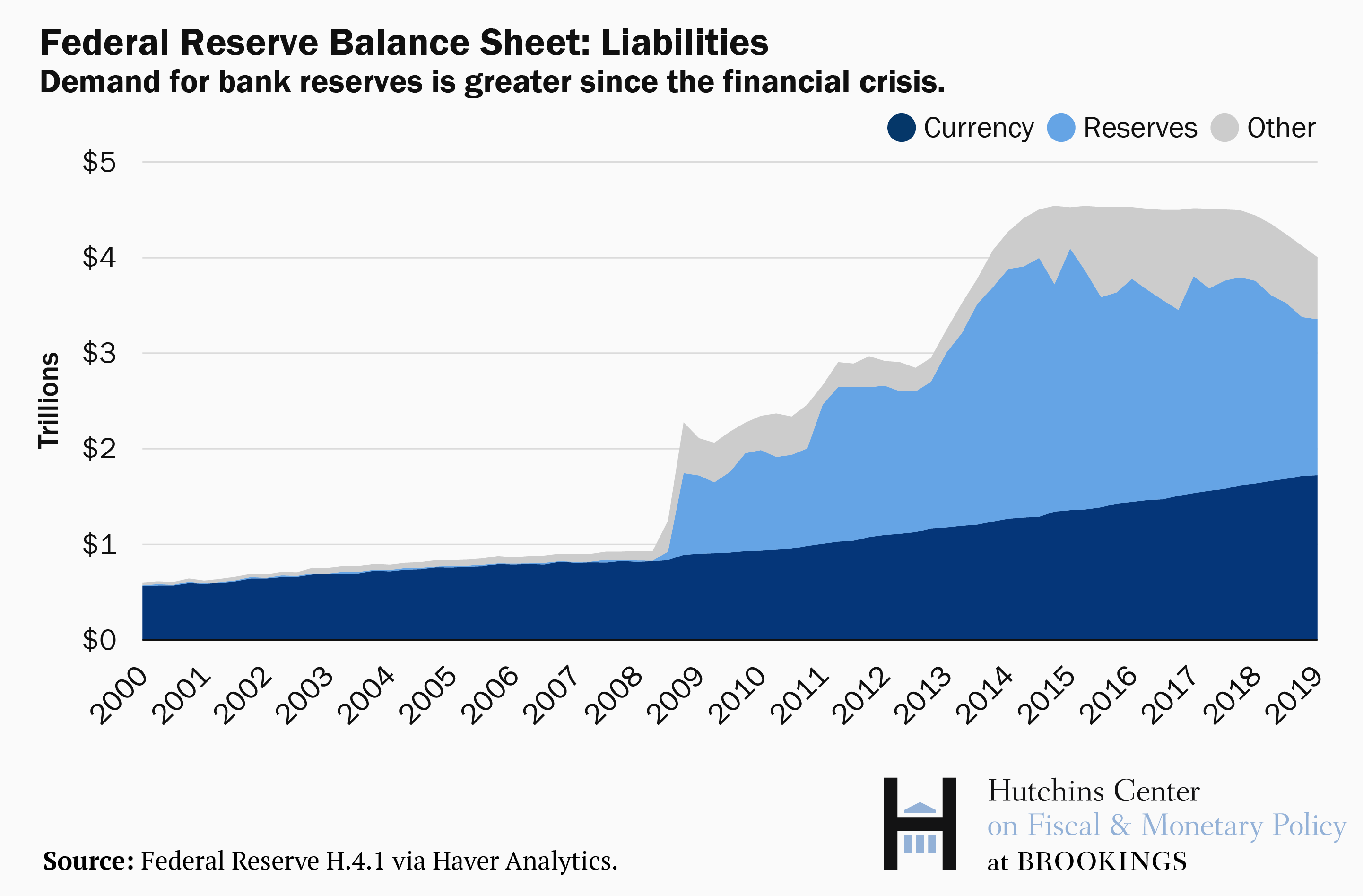

Like any financial institution, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet consists of liabilities (mainly outstanding currency plus funds that banks deposit at the Fed in what are known as “reserves”) and assets (mainly U.S. Treasury debt and mortgage-backed securities). What makes the Fed unique is that it can expand its balance sheet at will by (electronically) printing money (technically, bank reserves) and using that money to buy Treasury debt on the open market. The Fed posts details of its balance sheet regularly.

What’s been going on with the Fed’s balance sheet?

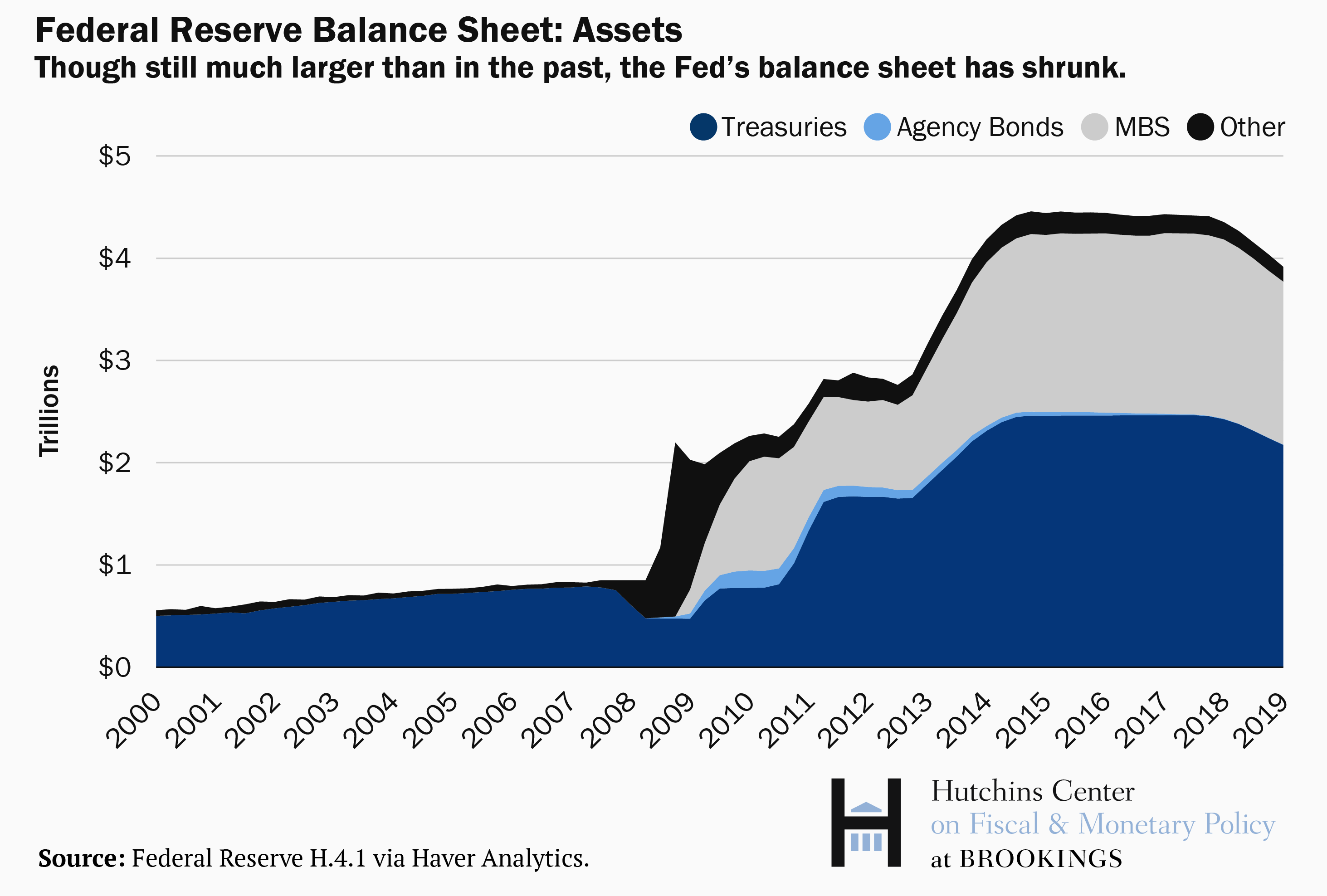

The Fed’s balance sheet expanded by over $3.5 trillion during and after the Great Recession as a result of trillions of dollars in bond-buying, known as quantaitive easing (QE). At its peak, the balance sheet was around $4.5 trillion, or the equivalent of 25 percent of GDP, compared to $850 billion, or 6 percent of GDP, before the Great Recession. The Fed began shrinking the balance sheet in October 2017 by not reinvesting the proceeds of all the bonds in its portfolio when they mature, a process that the Fed calls “balance sheet normalization” but others call “quantitative tightening.” This process has been criticized by some in financial markets and by President Donald Trump, who regard it as unwarranted tightening of monetary policy. The Fed argues that its primary monetary policy tool remains short-term interest rates and that the balance sheet normalization is a much more gradual change happening in the background. Furthermore, the shrinking of the balance sheet has not increased long-term interest rates by as much as some expected. The Fed says it plans to end the shrinking of the balance sheet by September. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has estimated that the balance sheet will end up at about $3.5 trillion, or 17 percent of GDP.

How does a large balance sheet change the way the Fed influences interest rates?

The Fed used to set interest rates by adjusting the supply of bank reserves. Banks are required to keep a minimum amount of reserves at the Fed. Because the Fed historically didn’t pay interest on these reserves, banks avoided keeping any more reserves than they needed to at the Fed, and instead lent “excess reserves” overnight to other banks that needed it in the federal funds market. The Fed influenced the interest rate at which reserves were borrowed or lent – the federal funds rate – by buying or selling Treasury securities in that market and adjusting the supply of bank reserves accordingly. The federal funds rate is a benchmark interest rate for all other short-term rates in the economy.

In 2008, after Congress gave it authority to do so, the Fed began paying interest on required and excess reserves (IOER). Instead of buying and selling Treasuries to adjust the supply of reserves and influence the fed funds rate, it influenced the fed funds rate by setting the IOER. No bank would lend reserves to another bank at a rate less than the rate it could receive by simply keeping cash parked at the Fed, so changes in the IOER tended to change the federal funds rate. (For a variety of reasons, federal funds have traded a tick below IOER in practice.) Under this approach, banks are willing to hold large amounts of deposits at the Fed because they are remunerated at market rates. This approach has been described as an “ample reserves” framework in contrast to the previous approach, which has been dubbed a “scarce reserves” framework. The new approach is also known as a “floor” system because the Fed’s IOER, set by fiat, establishes a floor on the federal funds rate. Under this approach, the Fed’s balance sheet will remain much larger than it was prior to the financial crisis.

Why did the Fed decide to keep its balance sheet larger than it was before the financial crisis?

One, the demand for currency – $10, $20, $100 bills – grows over time as the economy grows and prices rise. Despite all the talk of cashless transactions, there is still a strong global demand for currency. Since the Great Recession began, currency in circulation has more than doubled, from $829 million to $1.7 billion.

Two, and more significant, banks’ desire to hold reserves has increased. Since the financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act and other regulations increased banks’ capital and liquidity requirements. That is, banks are now required to maintain larger cash buffers to safeguard against a major shock like the one that happened in 2008. Recent research by the New York Fed estimates the minimum reserve balances that would be required for the eight largest domestic banks to meet their liquidity needs during a banking panic on a single day could be as high as $933 billion. Since reserves maintained at the Fed are banks’ main source of cash, banks’ overall demand for reserves is now much higher than it was prior to the crisis, as a result of regulation.

In addition, there are some technical reasons why banks might want to hold reserves more than Treasury securities (both of which are considered very safe, high-quality liquid assets under current regulations), related to the timing of intraday settlements and requirements under banks’ resolution planning, or “living wills.” Indeed, the Fed’s survey of primary dealers in March shows a median expectation that banks will maintain at least $1.2 trillion of reserves. Before the crisis, reserves never rose above $46 billion.

The changes to the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and the way it influences interest rates do not mean that the Fed is either tapping the brakes or pressing on the accelerator to influence the economy. This is simply a change in the way the Fed influences interest rates, as Chair Powell and other Fed officials have said.

What about the composition of the Fed’s balance sheet?

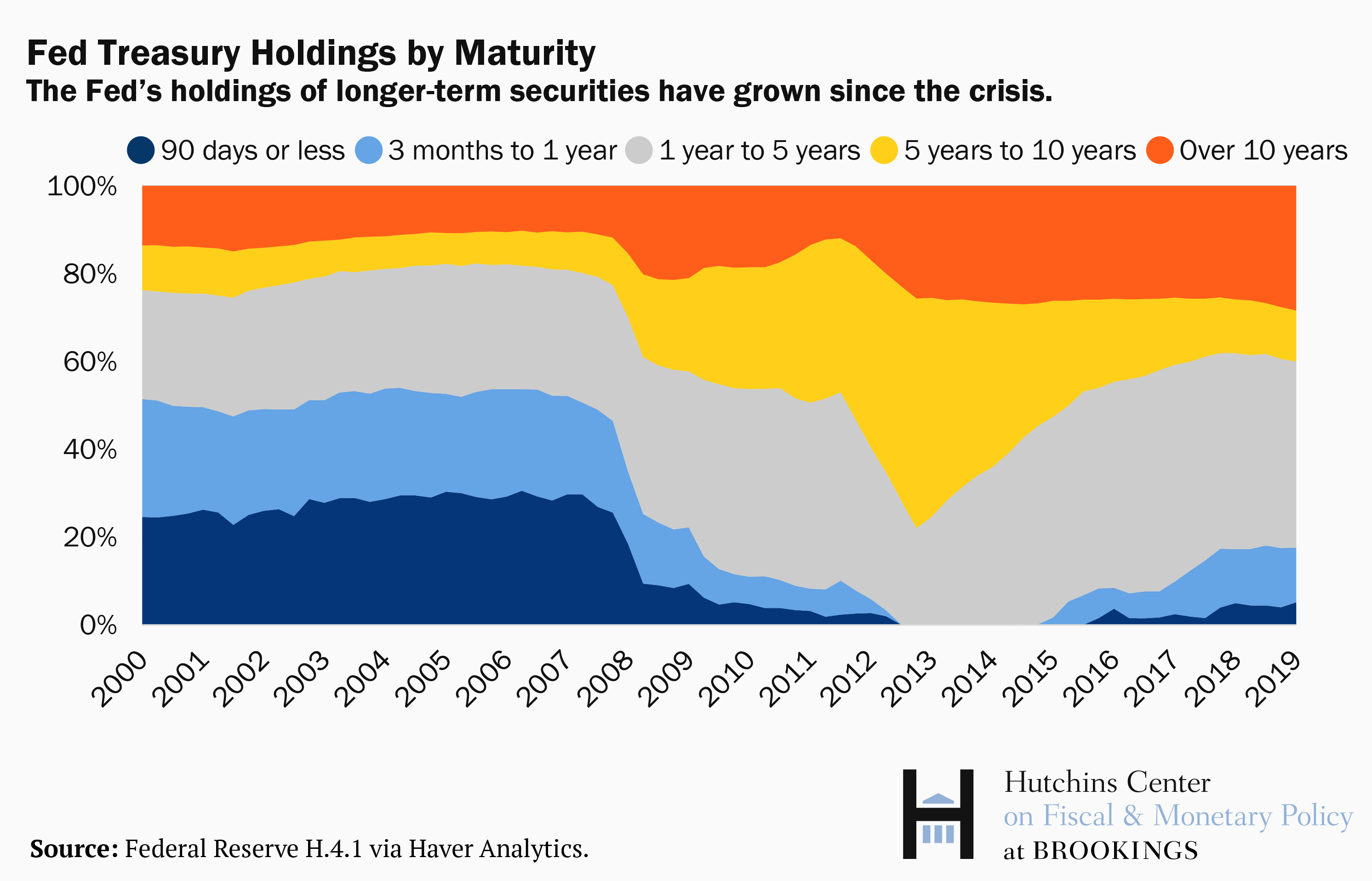

In addition to deciding the size of its balance sheet, the Fed has to decide which securities it will hold: Will it hold only Treasury securities, or will it also hold mortgage-backed securities (MBS)? Will it hold more short-term Treasury securities or more long-term Treasury securities? Holding MBS has been controversial; some see it as an unwise intervention in the markets that favors housing over other assets. Some members of Congress have called the Fed’s MBS purchases a form of fiscal policy, arguing the Fed is allocating credit to the housing sector instead of other parts of the economy, a decision usually left to Congress. The Fed has decided to return its balance sheet to a Treasuries-only portfolio eventually. It hasn’t decided on the composition of that Treasuries-only balance: more longer-term Treasury bonds or more shorter-term Treasury bills. Prior to the crisis, about half the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities matured in one year or less; today, that’s about 18 percent.

This was an intentional feature of the Fed’s crisis programs. In particular, the Fed’s Maturity Extension Program (MEP), also known as Operation Twist, was created to sell short-term treasuries and purchase long-term treasuries to lower long-term interest rates, which are important for business loans and mortgages. Research on the Fed’s asset purchase programs, including the MEP, estimate that they reduced the term premium (the additional interest that investors require to invest in longer-term bonds relative to several short-term bonds) by about 1 percentage point.

Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren has made the case that the Fed should shorten the average maturity of its balance sheet so that if it needs to implement a policy like Operation Twist in a future downturn, selling short-term bonds and buying long-term bonds, it has the ability to do so. But Chicago Fed President Charles Evans thinks this might not be the best idea. He argues that shortening the maturity of the Fed’s portfolio would increase longer-term interest rates and tighten financial conditions. To offset this, the Fed would have to keep interest rates lower during normal times, giving it less room to cut rates during the next recession. In May, Chair Jerome Powell noted that the Fed’s policy committee – the Federal Open Market Committee – had started to discuss this issue and plans to address it towards the end of 2019.

What concerns are there with the Fed’s new operating framework?

Though the Fed’s intention of implementing a floor system with ample reserves was done in part to maintain better control over interest rates, some economists, including David Beckworth of George Mason University, worry that this system isn’t working so well in practice. Recently, various short-term rates have risen and been unusually volatile. In particular, the federal funds rate has increased towards the top of the Fed’s target range. As a result, the Fed has made several technical adjustments to bring the federal funds rate down, lowering the IOER such that the spread at which it is set relative to the top of fed funds rate target is wider. Despite this tweak, various other short-term interest rates important for market functioning that traditionally trade below the IOER have risen above it. If the Fed can’t maintain control over interest rates, then it might have to make tweaks to its new “ample reserves” framework.

How can the Fed improve its control over short-term interest rates?

To give the Fed better control over interest rates, Bill Dudley, former president of the New York Fed, argues that the Fed should scrap the federal funds rate altogether as a target. The federal funds rate is a vestige of the old system, so attempts to control it are moot, he argues. Instead, the Fed should just focus on using rates that it controls directly, such as IOER and other administered rates. Economists at the Federal Reserve Board and the St. Louis Fed have argued (here and here) that the Fed should create a standing repurchase (repo) facility to keep short-term interest rates from rising above target and to decrease the overall demand for bank reserves at a given level of the IOER; the Fed has said it wants to see reserves at the smallest level consistent with conducting monetary policy efficiently and effectively. A repo facility would allow banks to borrow cash on a short-term basis from the Fed at slightly above market interest rates whenever they need it, similar to the Fed’s discount window, so they wouldn’t have to park so much money in reserves at the Fed. It also would effectively put a ceiling on short-term interest rates; no bank would borrow at a higher rate than the one they could get from the Fed directly. This might help keep the federal funds rate from rising above the Fed’s target. The IOER would serve as a floor for the federal funds rates and the rate on the standing repo facility would serve as a ceiling. Chair Powell said that the facility would be discussed by the FOMC in future meetings.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Fed’s bigger balance sheet in an era of “ample reserves”

May 17, 2019