When the nation’s schools closed to in-person learning, there was little warning and no precedent that could accurately predict the effects. Now that the dust has settled, it’s clear that higher-needs students suffered the greatest harm, such that they are now even further academically behind their more advantaged peers.

Yet, we have an early warning on our next major disruption in schools, which is only a year out: It’s a perfect storm of financial chaos brought on by the abrupt ending of federal pandemic relief funds, falling district enrollments, and slowing state revenues. While this next upheaval doesn’t involve sending students to learn from home for months on end, we do know that financial disruptions can take a toll on students. The question now is whether leaders will take action to ensure that our most vulnerable students don’t once again feel the brunt of the effects.

A financial U-turn means disruption, and distraction, for districts

The last few years have seen states and districts flush with cash, thanks to historic sums of pandemic relief aid (aka the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund or ESSER).

But come September 2024, districts – which have collectively spent $60 billion in ESSER funds for each of the two prior years – will suddenly have to make do without it. That leaves states and districts staring down a massive fiscal cliff. While amounts vary across districts, on average, that equates to a single-year reduction in spending of over $1,000 per student.

Many districts will need to right-size their budgets. This is likely to involve painful cuts – the type that can consume leaders in any district. The cuts will be especially challenging in districts that used relief money to add staff or maintain excess capacity that they would not have been able to afford otherwise. Leaders will have to cycle through gut-wrenching processes as they consider eliminating staff positions, programs, and extracurriculars. In some districts, leaders may even have to wrestle with closing schools, raising class sizes, and postponing pay raises. It will likely become difficult for leaders to maintain focus on improving academic outcomes while also navigating intense community dynamics as staff and families cope with change and uncertainty.

The cliff will be worse in districts serving high-need students

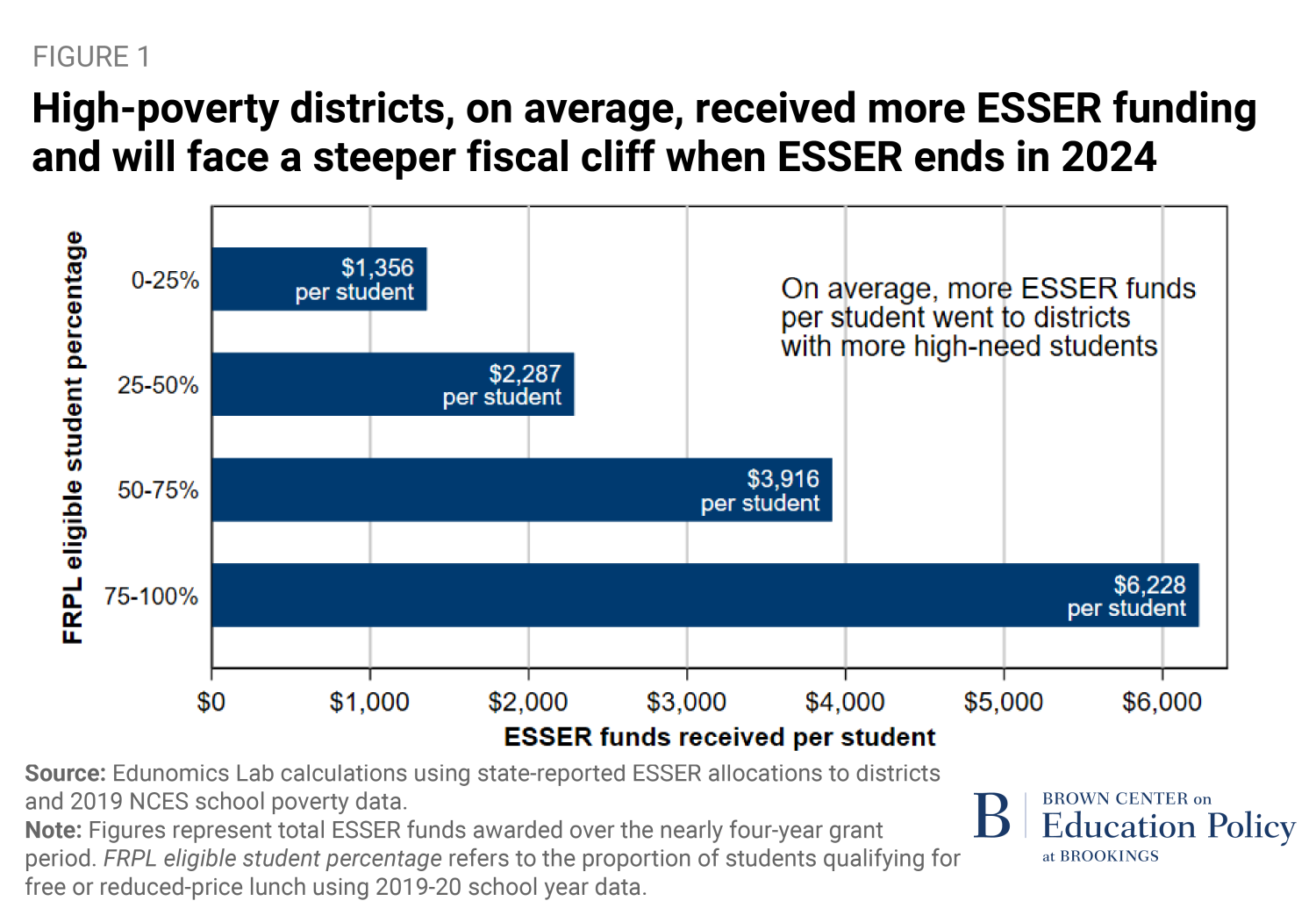

High-poverty communities will see sharper impacts to their school budgets in part because of how ESSER funding was structured: At the outset, ESSER funds were intended to provide greater levels of support for high-need schools. The figure below shows the total amounts of ESSER funds allocated to districts based on the share of free-lunch eligible students they served. Note that these figures are total allocations and were intended to cover spending over multiple years, not funds to be spent in any single year. As ESSER ends, those same districts now have more dollars to cut from their recent annual budgets.

While districts with complex student needs welcomed the dollars, spending these sums before the deadline has been complicated. While the average district is on track to spend down ESSER funds, in six states we examined, districts serving a high share of students in poverty appear to be spending their available dollars at a slower pace than their more affluent counterparts (see Figure 2). (Notably, the Public Policy Institute of California found the same trend in California.) A slower spending pace leaves a district with even more money in its 2023-24 budget, resulting in a larger year-to-year contraction as the cliff hits in fall of 2024.

In other words, districts serving our neediest kids have further to fall. Using Washington districts’ own projected FY25 budgets and an assumed steady spend-down of remaining ESSER funds through September 2024, we find that in high-poverty districts (over 75% poverty) the end of ESSER has a six percent impact on budgets, compared to two percent for districts serving more affluent students (under 25% poverty).

While not all states report budget projections, we analyzed prior-year financials in the other five states and found that the end of ESSER will have essentially the same imbalanced impacts on school budgets.

But it’s not only the percentage change in budget that sets them apart, it is also the sheer workload involved. While we anticipate that even those with large amounts left to spend will indeed deplete it by the deadline, with so much left to spend, some leaders in high-poverty districts may have no choice but to quickly invest those funds while simultaneously planning to eliminate those same investments.

Staff reductions will bring more churn in high-need schools, and can stymie progress on teacher diversity

Since over 80% of district budgets typically pay for labor, budget cutting often means staff reductions. While not all states track how districts use ESSER, data from those that do suggests that about half of ESSER is paying for labor expenses. And indeed, many districts have used their ESSER funds to hire even more staff. Simply put, when the ESSER money runs dry and the fiscal cliff hits, many districts will be left with little choice but to seek staff reductions.

Staffing cuts, if not managed appropriately, can wind up hurting both educators and students of color the most. In fact, in anticipation of the cliff, some districts are already imposing hiring freezes, eliminating unfilled positions, and laying off staff to cut costs. If history is any guide, with these types of staff reductions, the most vulnerable students experience the most disruption.

Where districts apply last-in-first-out (LIFO) policies to reduce their ranks, it’s the junior teachers who get pink slips. Since high-poverty schools tend to have a larger share of junior teachers, a larger share of their staff is shown the door.

Eliminating via attrition or unfilled positions might seem more palatable, but when those openings are disproportionately in hard-to-fill STEM or special education spots in high-poverty schools, the effects aren’t distributed evenly.

Junior teachers are also more likely to be among the district’s most racially diverse employees, thanks to a national push to diversify the education workforce in recent years. As districts move to downsize their workforce, they risk erasing the progress they’ve made toward improving the racial and ethnic diversity of their teaching staff.

In states with slowing revenue growth, finance policies could make things worse

The hope in many districts is that increases in state revenues will offset the loss of relief funds. In Massachusetts, a sizable boost in state spending will do just that for many of its districts. But in other states, slowing revenue growth is coming at a bad time.

Districts with high-need students depend more heavily on state funds, so any slowing in state revenue can worsen equity. Where legislatures do feel pressure to help out, some may expand permissions for districts to grow their local funds. In the Great Recession, when state revenues fell, low-income districts struggled more to offset the losses with local funding. Not surprisingly, the result was greater inequity between districts in affluent neighborhoods and their peers who didn’t have the option of raising as much money locally.

Then there’s the possibility of hold harmless policies—a tempting state policy option to reduce the negative impacts of budget cuts stemming from falling enrollment. While well intended, it too can have perverse equity effects, sometimes directing funds outside equity-driven state funding formulas. That’s because any extra state funding sent to a district via a hold harmless clause means less funding available to send to other districts in the state.

This time we can see it coming

It is no exaggeration to say that school finance is at an inflection point. And equity – in resources, staffing, and learning opportunity – hangs in the balance.

At the state level, we suggest leaders pencil out any proposed changes to revenue structures and find ways to ensure equity isn’t lost in transition. If states are considering new education spending, they might target it carefully to where needs are highest, e.g., to districts with the least capacity to raise local funds.

We encourage states and districts to take stock of their layoff policies before cuts bring unintended consequences. Where LIFO policies are in place (often codified in collective bargaining agreements), the time is now to go back to labor partners to negotiate a more equitable approach.

Some districts (including many in Ohio, for example) have grown their reserves, which could buy leaders some needed time to more gradually reduce their budgets. Though funneling money into reserves may be fiscally prudent, it shouldn’t take priority over students’ pressing academic needs.

While the pandemic took leaders by surprise, the coming financial turmoil is spelled out in district financial figures. That means leaders have the option of making deliberate, proactive choices. To preserve hard-fought equity gains, leaders will need to be eyes-wide-open on how their choices play out for the neediest students.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).