The past six years have witnessed the most significant reshaping of the federal workforce in recent history. On the one hand, government clearly has lost weight. The total number of full-time federal employees has declined, as has the number of federal middle-level managers. On the other hand, government has gotten much taller, at least as measured by the number of layers at the very top of the federal hierarchy. This changing shape means that ordinary Americans will be less likely to contact a federal employee when they call a government 800 number, write an office, or use a service. It also means that the nation’s elected and appointed leaders will be further from the front lines, and less likely to know what the public is getting for its tax dollars.

POLICY BRIEF #45

Last year set records in more than just home runs and independent counsel budgets. It represented a banner year in the number of titles open for occupancy at the top of the federal hierarchy. Never has a president had so many layers of senior executives, whether political appointees or career civil servants, juxtaposed between him and the front lines of government. At the same time, never have fewer front-line employees actually delivered the goods for government. Ten years of downsizing have hit hardest the lower levels of the government workforce, as the number of senior and middle-level federal employees has remained virtually unchanged.

Without discounting the significant downsizing that has occurred, only one of the two ingredients for a leaner, more efficient government is in place. The girth of government—measured by the total number of federal employees—may be shrinking, but its height—measured by the management tiers between the top and bottom—continues to climb. Every year fewer front-line employees are reporting upward through what appears to be an ever-lengthening chain of command.

The Girth of Government

There is no question that the girth of government is shrinking. The proof is in the federal phone books and employment files.

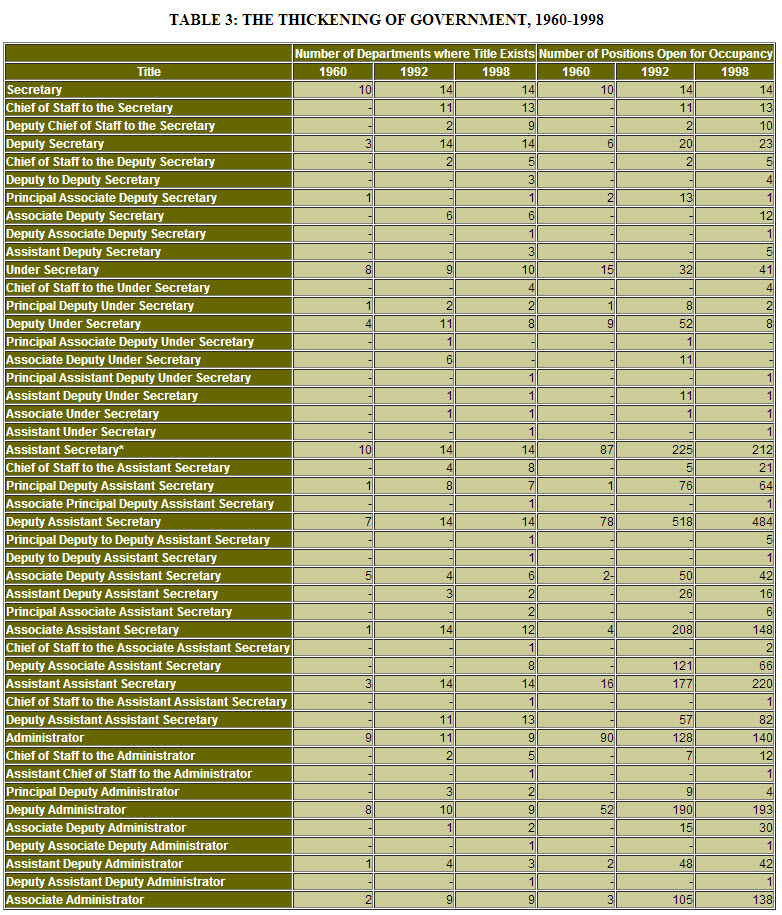

Start at the very top of the federal hierarchy, where presidential appointees and senior career executives work. According to a careful coding of the winter 1998 Federal Yellow Book, 2,462 federal executives carried some variation of the five top titles in a federal government department: secretary, deputy secretary, under secretary, assistant secretary, and administrator. That number includes everything from chiefs of staffs to associate under secretaries, assistant inspectors general to principal deputy administrators. That figure had increased more than fivefold from 1960 to 1993.

To Clinton’s credit, his administration has held the total number of executives in check. Those 2,462 officials represent an addition of just fifty-four since January 20, 1993, and include seventy-eight in the newly independent Social Security Administration (SSA). Subtract those positions from the count, and the Clinton administration actually lost weight.

The administration also has reduced the number of middle managers. The federal government employed 126,000 middle managers in 1998, down from 161,000 in 1993, dropping the total to its lowest level in fifteen years. The government employed eight rank-and-file workers for every supervisor in 1993; by 1997, the ratio had risen to eleven to one. Moreover, nearly every department, not just Defense, lost mid-level supervisors. Only the departments of Justice (up 2,000) and State (up eighteen) expanded middle management ranks. Interior and Treasury both lost roughly a sixth of their middle managers; Agriculture, Commerce, Labor, and Transportation, almost a fifth each. Other departments shrank by higher margins: Education and the General Services Administration cut more than a third; the Environmental Protection Agency and Housing and Urban Development, almost two-fifths; Energy and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, more than half; and the Office of Personnel Management, more than two-thirds.

How did the administration lose the weight? Downsizing began with military base closures in the late eighties. It accelerated in 1993, when Clinton issued an executive order mandating a 100,000-position reduction in total employment, and again in 1994, when he signed the Workforce Restructuring Act. The two initiatives clipped a grand total of 272,900 positions. Although presidential appointees and senior executives accounted for none of the reductions, and middle managers formed just ten percent of the total cutback, Clinton clearly slowed the growth rate in both categories, which had expanded substantially under presidents Reagan and Bush.

Congress also gave the Clinton administration resources to offer senior and middle-level executives $25,000 buyouts as incentives to step down. There is no question that the inducements allowed the administration to shrink the number of retirement-eligible executives and managers. Of 83,000 buyouts between 1993 and the first half of 1995, for example, almost three-quarters involved recipients who already were eligible for early or regular retirement. Whether those employees would have departed in due course anyway is in some dispute, but the fact remains that they did vacate at least some of the middle-level management positions.

Vice President Al Gore also strengthened the administration’s push for job cuts, making the 272,900-position reduction a centerpiece of his reinventing government campaign. Much as one can criticize his reluctance to attack the upper reaches of the hierarchy, Gore gave the effort to crop the lower ranks his full attention. He endured endless meetings on some of the most boring topics known to management science and emerged energized. Certainly, he changed the national dialogue about the public service, moving attention away from power-hungry bureaucrats to creativity-stifling bureaucracy. This deliberate semantic shift, which first appeared in the 1992 presidential campaign, allowed the Clinton administration to simultaneously claim victory in the war on bureaucracy while liberating the bureaucrats from a host of needless rules.

The Height of Government

Just because the number of senior executives or middle managers has remained steady or declined does not mean that the number of layers they occupy has held constant or diminished. At the middle levels, for example, many agencies have reduced the number of managers by merely assigning different titles. According to the General Accounting Office, forty-one percent of the downsizing of supervisors at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, involved such reclassification, as did forty percent of the cuts at the Bureau of Land Management and thirty-five percent at the Federal Aviation Administration. The Social Security Administration cut nearly 2,800 middle-level supervisory titles from 1993-1998, but created 1,900 new nonsupervisory titles, including 500 team leaders and 1,350 management support specialists.

SSA is not the only agency to use creative titles to keep the layers in place. There appear to be more team leaders today in government than in all of Little League, Pop Warner football, and peewee soccer combined, but there may have been no real cutbacks in the layers between the heads and bases of agencies. An interfering manager by any other name can stall just as effectively.

The continued layering of government is more apparent at the top. There, the Clinton administration has failed to stem the generation of new titles. Indeed, the administration has witnessed the most significant addition of layers in modern executive history. Since 1993, the fourteen government departments have created sixteen new titles at the top, including a stunning number of new alter ego deputy posts. Government’s top tier may not be getting wider, but it is most certainly getting taller.

TABLE 3-5: TITLES OPEN FOR OCCUPANCY, WINTER, 1998

|

Among the soon-to-be-classic new titles are deputy to the deputy secretary, principal assistant deputy under secretary, and associate principal deputy assistant secretary. Other elegant appellations include: assistant chief of staff to the secretary, deputy associate deputy secretary, assistant chief of staff to the administrator, and chief of staff to the assistant administrator. These are classic lieutenants primarily charged with standing in for their superiors. It is hard to imagine how assistant chiefs of staff contribute to greater accountability, higher performance, or more presidential control. Mostly, they contribute more delays and needless interference. They also elevate the self-importance of their bosses.

The Clinton totals would have been even higher had three titles not disappeared along the way: principal associate deputy under secretary [in Energy], associate deputy under secretary [in six departments], and an associate assistant administrator [twelve had existed in Commerce]. In total, the Clinton administration created nineteen new titles and removed three, yielding a net of sixteen. To put the numbers in historical context, this administration has created as many new titles during its six short years as the past seven administrations created over the preceding thirty-three years.

(Table 3)

To be fair, only four of the new titles exist in more than one department. But if the past is prologue, expect the titles to multiply. A deputy will go to a conference or page through the Yellow Book and find out that his or her counterpart in another department has a loftier title. That is how title creep occurs. But for the secretary title, which has existed since the first Congress created the first department, each title in the phone book originated in only one department.

That is why it is so important to attack titles early. Unfortunately, even as the Clinton administration appears to be watching every last digit that might be added to the total civilian headcount, no one appears to be monitoring the new layers. Departments are mostly free to invent new positions as their principals wish.

Whatever the cause, the layering increases the distance that ideas must travel up to reach the secretary and guidance must travel down to the front lines of government. More hands must touch the paper, more signatures grace the page, and more eyes read the memos. It is impossible for the top to know what the bottom is doing when the bottom remains thirty, forty, or more layers below; it’s impossible for the bottom to hear the top when messages go through dozens of interpretations on their journey down. Like the game of gossip in which messages become hopelessly distorted as they are relayed from child to child, the layers merely add to the potential confusion and loss of accountability between the top and the bottom.

The Disappearing Bottom

Presidential appointees and senior managers were not alone in surviving the downsizing mostly untouched. The middle levels of government remained intact. Even as the number of middle-level managers fell from 161,000 to 126,000, the number of middle-level employees increased from 485,000 to 510,000. It turns out that workforce diets can be just as frustrating as human diets. Some parts of the bureaucratic body take the brunt, while others resist. Driven to prove that it could cut federal employment just like a Republican administration, yet reluctant to impose sweeping reductions-in-force, the Clinton administration opted for attrition as its primary downsizing tool. People who left government voluntarily would not be replaced.

As a result, the federal cutback hit the lower levels of government the hardest. After all, that is where the pay is lowest and attrition rates the highest. The number of employees in the lower grades of the federal general employment schedule dropped by more than 170,000 between 1993 and 1997, while the number of blue-collar jobs fell an additional 90,000. At the same time, the average employment grade of the lower-level employees who remained on the job actually increased by its largest margin in a decade, meaning that more jobs were removed at the bottommost levels than anywhere else.

No one quite knows how the disappearing floor will influence the actual delivery of services. In some cases, it certainly will result in greater efficiency with the advent of new technologies. In other cases, a basic service will still be delivered, but by a contractor, a nonprofit agency, or a state and local employee. In still other cases, the government will use a new delivery system entirely, replacing direct regulation or spending by the federal government with regulation by markets or by tax expenditures. Clearly, federal employees are moving off the front lines, losing some margin of contact with the people they serve. To the extent the federal government replaces its own employees with contractors and grantees, while encumbering state and local employees under unfunded mandates, it merely transfers its size to a hidden workforce. And that, in turn, encourages Americans to believe they can have it all: a government that is getting smaller year after year, yet a mission that continues to grow.

As the bottom of government has thinned under the downsizing, the middle of government has swollen. Not only did the total number of middle-level employees grow, but the loss of 35,000 managers also failed to lower the average pay grade. Indeed, the average grade for the middle levels of government actually has risen over the past six years, despite the loss of nearly one-quarter of what should have been the more highly graded managerial posts.

The relative stability in the middle-level ranks could signal the presence of one or both of two conditions. First, it could be that managers who were reclassified into positions outside management ranks were left at the same grade. Second, it could be that most of the vacated positions were backfilled, meaning that the occupant left, but the job and grade, sans managerial responsibilities, were occupied by the person next in line. Neither Clinton’s 1993 executive order nor the Workforce Reduction Act required that the more highly graded jobs be forever abolished upon the incumbents’ departure. The hierarchy most certainly lost weight in the total number of employees, but actually gained weight as measured in the average grade of the employees who remained. This may be a diet that any overweight American would gladly follow, but it is not necessarily healthy for assuring government accountability.

It is not exactly clear where the bottom-level jobs went. No doubt some disappeared forever; others likely ended up in service contracts. Lacking careful tracking data, one can only speculate. Although the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) specifically asked agencies to collect information on any shift of jobs from employees to contractors, it has not monitored the data, if any data were kept at all. OMB had to depend on agencies to keep caps on contracting despite the fact that those agencies still had to deliver the same amount of goods and services. Congress and the president wanted a government that most certainly looked smaller, but delivered at least as much, if not more.

As the American Federation of Government Employees’ late president John Sturdivant warned, “I would just hope that the Contract with America does not provide for more contracting out of America…Downsizing federal employees while upsizing contract employees will only wrongsize the Federal Government’s overall work force.” No one knows for sure whether his worries were well placed, but the circumstantial evidence suggests that only a portion of the jobs could have ended up as service contracts. Whether the rest wound up in unfunded mandates or moved up into the relative safety of the middle level is anyone’s guess.

The Circle in the Pyramid

Step back from all the numbers and layers, and one simple fact emerges: the federal hierarchy is shifting from a traditional bureaucratic pyramid into a circular, ultimately elliptical shape. Last year marked the first time in modern history that the number of middle-level federal employees outnumbered the lower-level employees. In 1993, there were 1.2 lower-level employees (General Schedule 1-10) for each middle level employee (General Schedule 11-15). Today, the lower-level numbers have fallen to 0.93 for every middle-level employee. If current trends hold, the federal government’s last front-line employee will retire sometime in 2030—his or her job finally contracted out or downsized forever.

Part of the shift reflects the natural evolution of work. The bottom of government has slimmed for decades as new technologies rendered front-line jobs obsolete. Between 1954 and 1961, for example, the federal government hired 1,800 new lawyers, 45,000 engineers, 16,000 accountants, 12,000 scientists, 4,000 social scientists, and 20,000 transportation experts, while cutting 2,000 messengers, 14,000 typists, and 10,000 general secretaries.

But much of the recent shift reflects the use of attrition as the primary tool of downsizing. It stretches credulity to argue that nearly 300,000 lower level jobs suddenly became obsolete in 1993. The federal government mostly got rid of the jobs that were the easiest to get rid of, meaning the ones with the highest attrition and the lowest political profile.

The rest of the pyramid will still exist in this circular future, of course. It will just reside outside of the federal headcount in the millions of people who will work for contractors, grantees, and state and local governments delivering services on the federal government’s behalf. As long as the federal mission continues to grow, and Clinton did not indicate in his recent State of the Union message that he intends it to stop, the faithful execution of the laws will rely more on writing careful contracts, grants, and mandates than on the traditional chain of command between elected representatives and the career workforce below. That observation reflects neither a liberal nor a conservative political position. It simply describes the way government must operate given the pressure to do more with less.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).