Teens vs. Toddlers: When to Intervene?: Third in a four-part series examining the debate over when to intervene to improve social mobility.

Social mobility will be enhanced by interventions in both early childhood and in adolescence, as the last two posts have shown. Given limited resources, where should policymakers invest?

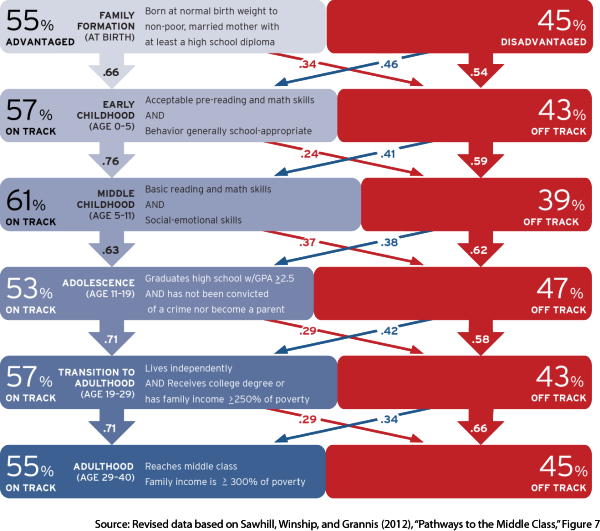

In Pathways to the Middle Class, we explored the chances of an individual succeeding in adulthood (as measured by income), based on achievements in early childhood and adolescence. As we argued yesterday, someone who prospers as a teenager (graduating from high school with a decent GPA, avoiding teen pregnancy, and avoiding criminal conviction) is very likely to succeed as an adult even if they did not succeed at earlier stages.

So should policy to re-tasked towards teens? Not necessarily. A broader view of the evidence finds, in short, that nothing succeeds like success. Individuals who are successful in early stages are more likely to be successful at subsequent stages. For example, 76% of children who are school-ready in early childhood are succeeding in school in middle childhood, compared to just 41% of those who were not school ready in the early years. A policy agenda that only aims to improve adolescent outcomes would undervalue the benefit of earlier intervention.

Probability of Being on Track or Falling Off Track, Conditional on Previous Experience

On the other hand, it would be mistaken to conclude that policy is only necessary in the early years. Early success does not guarantee adolescent success. Rather, 37% of those who succeed in middle childhood do not reach the success benchmark in adolescence. We need policies in adolescence to help individuals stay on track through what is an especially risky stage.

Overall, what we learn from the Pathways report is that the best way to guide individuals toward adult success is to encourage their continued success by intervening multiple times, as needed.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation argues as much in their new Kids Count policy report, calling for high-quality, coordinated programs to get children on the right track from the start, and to keep them there. In the final part of this series, tomorrow, we’ll estimate the potential impact such an approach might have on the proportion of people who climb the ladder to the middle class.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Success Begets Success

November 6, 2013