Social Security is critically important for retired and disabled Americans, providing about 1/3 of their income on average.1 But the program faces a long-run financing shortfall. By 2034, the trust funds which have been supplementing dedicated Social Security payroll tax revenues in recent years are projected to be depleted. At that time, incoming tax revenues will be sufficient to pay only about 80% of scheduled benefits.

Social Security also faced a financing challenge back in 1983, prompting significant reforms—including an increase in the retirement age—that averted the immediate crisis and put the program on a stable footing for decades. In one sense, the system is not yet in as urgent a situation as it was before the 1983 reforms. Then, without action by Congress, Social Security was just months away from being unable to pay full benefits on time. But the changes that are required to put Social Security on a stable footing over the next 75 years are significantly larger than they were in 1983. In this post, we explore the Social Security funding challenge in 1983 and its implications for the shortfall today, as well as options for the future of the program.

Our conclusions are as follows:

- In 1983, Social Security insolvency was just months away, and changes were necessary to ensure promised benefits would be paid. Today’s situation is much less urgent—the system is expected to be able to pay benefits in full for at least another 10 years.

- But the changes that will ultimately need to be made now are significantly larger than they were in 1983—if we wait until the last minute, as was done in 1983, the changes will have to be larger still.

- The 1983 reforms were expected to ensure solvency through 2060. However, weaker economic performance and higher rates of disability claims meant larger deficits in the system than expected, leading the date of asset depletion to move up to 2034.

- It was clear even in 1983 that further changes would have to be made eventually. The 1983 reforms ensured solvency for 75 years, but with rising deficits over time as the baby boom generation retired, that was not sufficient to put the program on a stable footing in perpetuity.

- The lessons of 1983 argue for acting sooner than later, because this spreads the costs across more generations and allows for policy changes to be implemented gradually. The 1983 financing crisis also points to the importance of having a significant cushion so that economic downturns don’t lead to Social Security financing crises. This could include the buildup of a trust fund or the authority to use general revenues when necessary.

Each year, the Social Security Trustees publish projections of the program’s finances—revenues from payroll and other taxes and interest on the trust funds versus benefits expected to be paid—over a 75-year horizon. These projections account for expected changes in the economy as well as demographics. An often-cited summary statistic is the actuarial balance—the increase in revenues or cut in benefits as a percent of payroll that, if implemented immediately, would be sufficient to achieve solvency over a 75-year horizon. Solvency is defined as ending the period with assets in the trust fund equal to one year’s expenditures.

How do projections of today’s imbalances compare to those before the 1983 reforms?

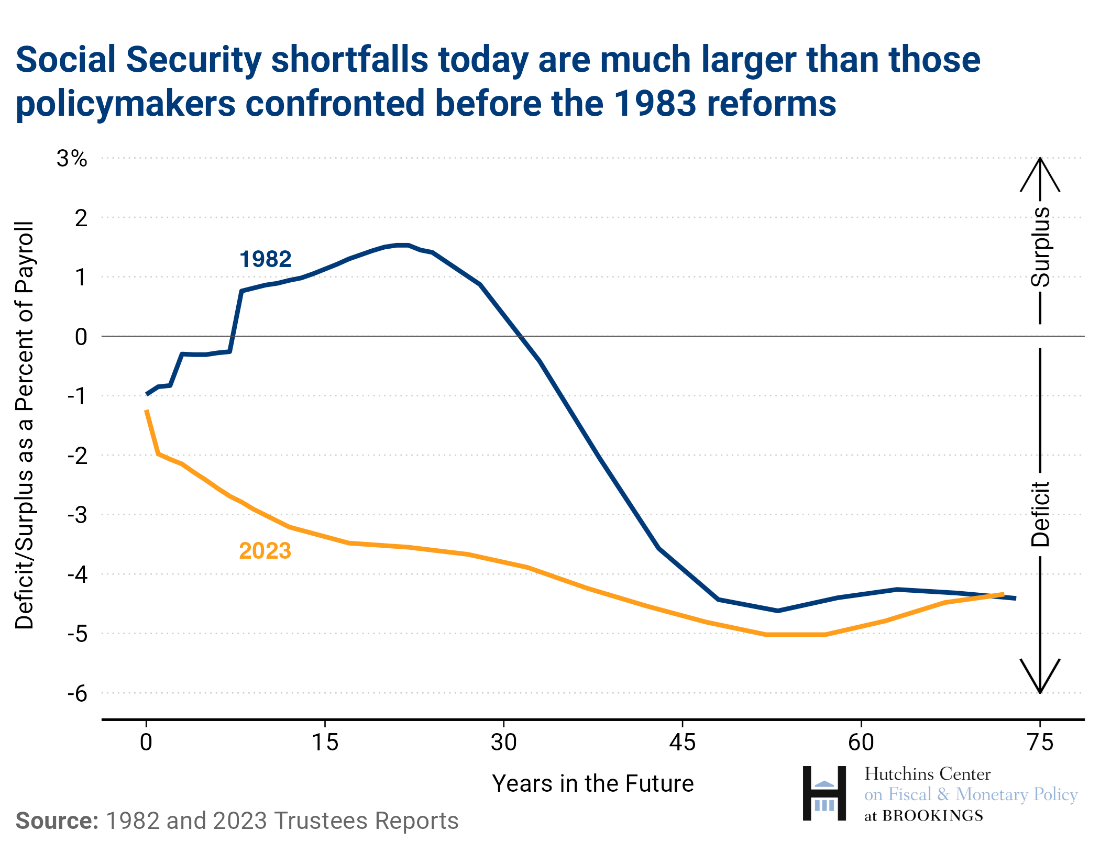

The figure below compares the projected shortfalls—the excess of expenditures over revenues—in 1982 (the last Trustees’ report before the 1983 reforms) and 2023. In 1982, the actuaries projected small deficits through 1990 (line is below zero), at which time already enacted but not yet implemented increases in the payroll tax were expected to be sufficient for the program to run surpluses (line is above zero) through 2010. In contrast, the Social Security system is now running a sizable deficit—expected to equal 1.2% of payroll this year—and that deficit is projected to rise going forward.

Comparing the 75-year actuarial deficits now versus those projected in 1982 shows how much larger the challenge is today: To put the program on stable financial footing today would require an immediate increase in revenues or cut in benefits (or combination of the two) equal to 3.61% of payroll; in 1983, the actuarial balance under the intermediate projections was 1.82% of payroll, meaning that the required adjustments to revenues and/or benefits are twice as large today.

Since 2004, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) also has published long term projections of Social Security solvency; these differ from those of the Trustees because CBO makes different economic and demographic assumptions. CBO’s estimate of the actuarial balance is 5.1% of taxable payroll, considerably larger than the Trustees’ estimate. But the Trustees and CBO both expect the trust funds to be depleted in 2034.

In 1979, the Social Security Trustees predicted that, under the intermediate set of assumptions (versus the low-cost and high-cost assumptions), the program would be solvent through 2032. However, recessions in 1980 and 1981 worsened the program’s finances. By 1982, the Trustees were projecting that the fund would be insolvent by July 1983.

In 1979, assets in the trust funds were just 26% of annual program outlays, and incoming revenues were expected to roughly equal benefit costs. Under those conditions, the program was vulnerable to economic downturns, as even small changes in revenues could make the program insolvent.

What did the 1983 reforms do?

The 1983 reforms included measures to address both the short-term financing crisis and the long-term challenges arising from the retirement of the baby boom generation. Most measures were implemented immediately, including a six-month delay in the cost-of-living adjustment to benefits, an acceleration of already enacted payroll tax increases, an extension of Social Security coverage to new Federal employees and non-profit employees, and the taxation of benefits for high-income beneficiaries. In addition, the normal retirement age (the age at which beneficiaries are eligible for full benefits) was increased from 65 to 67, but the increase only began in 2000 and was then phased in slowly through 2022. The actuaries projected that these reforms would keep the system solvent through 2060.

If the 1983 reforms solved the problem, why do we face such a large shortfall today?

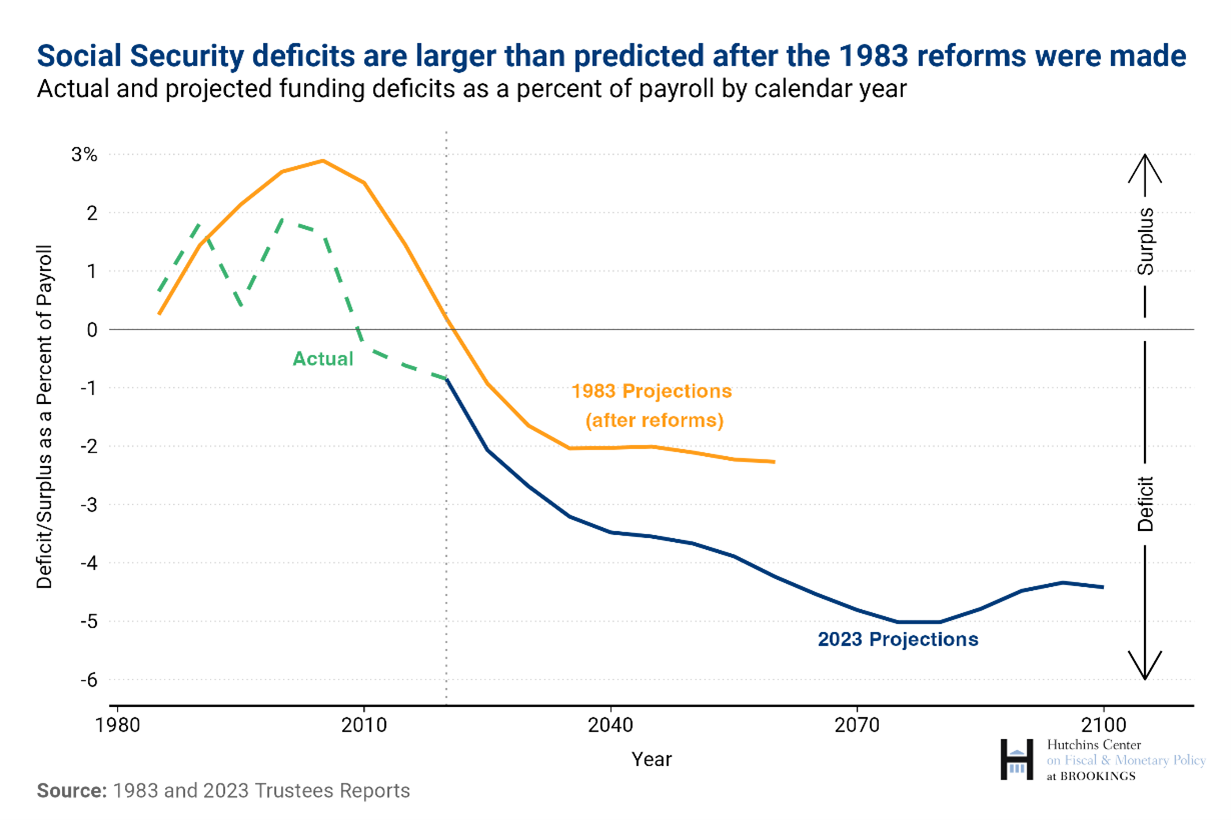

In 1983, after the reforms had been enacted, the Trustees projected that the program would be solvent through 2060, whereas they now expect trust fund depletion in 2034. As shown in the figure below, Social Security deficits were larger (or surpluses were smaller) than anticipated between 1985 and 2023, on account of worse-than-expected economic outcomes and a higher rate of disability benefit claiming.

But even if the Trustees projections in 1983 had been accurate, there would still be a large shortfall today. It has long been anticipated that the retirement of the baby boom generation, which began around 2010, would lead to increased spending on Social Security. The 1983 reforms were expected to achieve solvency for 75 years, with surpluses during the relatively low spending years (before many of the baby boomers retired) offsetting deficits in the later years. Even in 1983, the actuaries expected the Social Security system to start posting deficits in about 2025 (which would be financed for a time by the rundown of trust fund assets), and they expected there to be actuarial imbalances that would have to be addressed by future legislation.

What happens if the trust fund runs out?

After the trust fund runs dry, Social Security will receive income from payroll taxes sufficient to cover only about 80% of benefits. How the Social Security system will address the shortfall is not clear: Social Security is both legally required to pay benefits and legally prohibited from using any revenues other than those dedicated to the program.

In 1982, the Trustees report said “without corrective legislation … the trust fund will be unable to make benefit payments on time,” which suggested that the plan was to delay benefits for everyone if funds were insufficient. (This is the same procedure that Treasury planned to use when faced with a binding debt limit.) Other possibilities include paying benefits in full for lower-income beneficiaries while delaying benefits for others. As with the debt limit, the inability to make payments doesn’t change the government’s liabilities: Unless Congress changes the laws, people will still be entitled to full benefits and would ultimately receive them when funds became available.

The main options fall into three buckets: (a) reduce Social Security benefits; (b) raise Social Security revenues, either by increasing payroll tax revenues or by raising other taxes and dedicating the proceeds to the Social Security system; or (c) allow general revenues to be used—i.e. deficit financing. In addition, policies that affect the growth of the economy—by increasing immigration, raising productivity, or increasing labor force participation, and policies that make Social Security coverage universal (some employees, including certain state and local government workers, are currently not covered) could also help. The Fiscal Ship, the Hutchins Center’s computer game on the federal budget, shows how a number of different options that have been considered would affect the federal budget.

What lessons should we take from 1983?

The decision taken in 1983 to address the long-term financing problem rather than just the immediate crisis had several benefits. First, it helped spread the costs of the demographic transition across more generations. Second, it allowed for the buildup of a sizable trust fund that helped insulate the Social Security system from recessions. Finally, it allowed policymakers to raise the retirement age without political backlash because the changes were so far into the future and so gradual.

The lessons of 1983 argue for acting sooner than later. They also point to the importance of having a cushion so that economic downturns don’t lead to Social Security financing crises. This could include the buildup of a trust fund or the ability to use general revenues when necessary.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- For retired beneficiaries, Social Security provides about 30% of income; for disabled beneficiaries, it provides about 60%.

Commentary

Social Security: Today’s financing challenge is at least double what it was in 1983

September 18, 2023