For decades, we have been hearing that the baby-boom generation was like a pig moving through a python–bigger than the generations before and after.

That’s true. But that’s also a very misleading metaphor for understanding the demographic forces that are driving up federal spending: They aren’t temporary. The generation born between 1946 and 1964 is the beginning of a demographic transition that will persist for decades after the baby boomers die, the consequence of lengthening lifespans and declining fertility. Putting the federal budget on a sustainable course requires long-lasting fixes, not short-lived tweaks.

First, a few demographic facts.

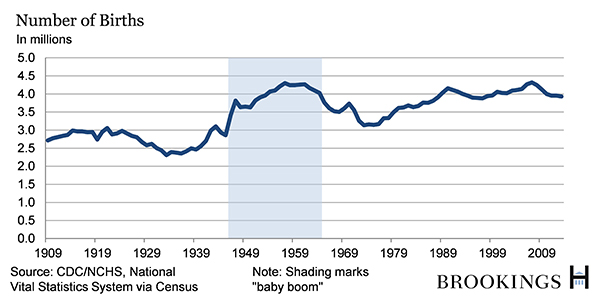

As the chart below illustrates, there was a surge in births in the U.S. at the end of World War II, a subsequent decline, and then an uptick as baby boomers began having children.

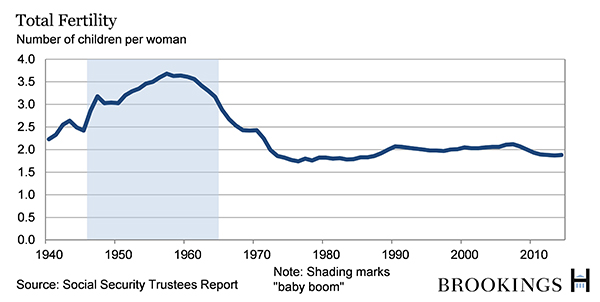

Although the population has been rising, the number of births in the U.S. the past few years has been below the peak baby-boom levels, possibly because many couples chose not to have children during bad economic times. More significant, fertility rates–roughly the number of babies born per woman during her lifetime–have fallen well below pre-baby-boom levels.

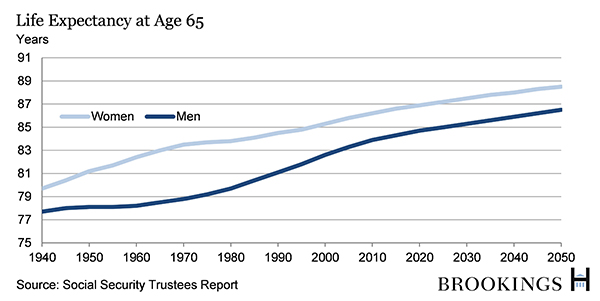

Meanwhile, Americans are living longer. In 1950, a man who made it to age 65 could expect to live until 78 and a woman until 81. Social Security’s actuaries project that a man who lived to age 65 in 2010 will reach 84 and a woman age 86.

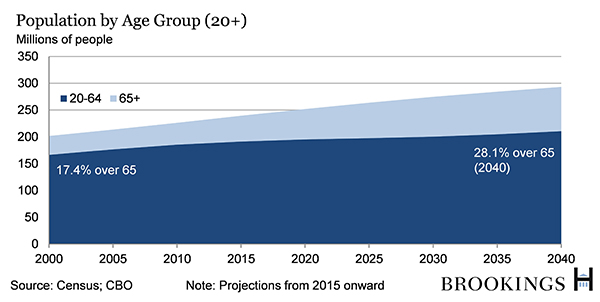

Put all this together, and it’s clear that a growing fraction of the U.S. population will be 65 or older.

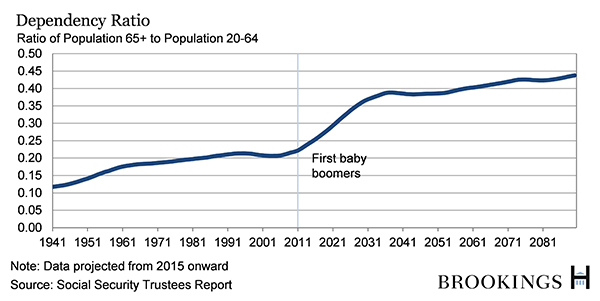

The combination of longer life spans and lower fertility rates means the ratio of elderly (over 65) to working-age population (ages 20 to 64) is rising. As the chart below illustrates, the ratio will rise steadily as more baby boomers reach retirement age–and then it levels off.

Simply put, this doesn’t look like a pig in a python.

So what do these demographic facts portend for the federal budget? In simple dollars and cents, the federal government spends more on the old than the young. More older Americans means more federal spending on Social Security and Medicare, the health insurance program for the elderly. On top of that, health care spending per person is likely to continue to grow faster than the overall economy.

The net result: 85 percent of the increase in federal spending that the Congressional Budget Office projects for the next 10 years, based on current policies, will go toward Social Security, Medicare and other major federal health programs, and interest on the national debt.

Restraining future deficits and the size of the federal debt mean restraining spending on these programs or raising taxes–and probably both. One-time savings or minor tweaks won’t suffice. Nor will limiting the belt-tightening to annually appropriated spending.

The fundamental fiscal problem is not coping with the retirement of the baby boomers and then going back to budgets that resemble those of the past. The fundamental fiscal problem is that retirement of the baby boomers marks a major demographic transition for the nation, one that will require long-lived changes to benefit programs and taxes.

Editor’s Note: This post originally appeared on

The Wall Street Journal’s Washington Wire

on December 18, 2015.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Hutchins Center Explains: Budgeting for aging America

December 21, 2015