Amidst growing frustration with the cost of higher education, complaints also abound about its quality. One critique, launched in the book Academically Adrift by two sociologists, finds little evidence that college students score better on measures of critical thinking, writing, and reasoning after attending college. This is something of a paradox, since strong evidence shows that attending college tends to raise earnings power, even for students who start with mediocre preparation.

Our recent study uses a different approach to assess the value of a college education. We find that the particular skills listed by a college’s alumni on their resumes predict how well graduates from those schools perform in terms of earning a living, meeting debt obligations, and working for high-paying or innovative companies. Since jobs requiring more valuable skills typically require at least some college education, this finding suggests many students are gaining valuable skills from college. But the variation in alumni skills across schools is wide, even after considering the aptitude of the students in terms of their pre-admission test scores. This variation implies that what one studies and where have big effects on economic outcomes.

Skills versus degrees

It is widely known that education raises individual earnings, but education—measured in years of study or level of degree—is a very rough measure of learning. Thus, it is not surprising that studies consistently find that skills are an important predictor of economic outcomes. People with higher test scores—another measure of learning—earn higher wages, even with the same level of education. Likewise, graduates with technical degrees earn more, as do workers in occupations requiring more STEM skills. At the international scale, performance on standardized exams has a much stronger statistical relationship with economic outcomes than do years of education, according to a new OECD study.

How we valued skills by college

Using data from the company Burning Glass, we calculated the average salary listed for distinct skills based on 3 million job vacancy ads. To match these skills to colleges, we used data from LinkedIn’s college profile pages, which show the 25 most common skills (e.g., customer service, Microsoft Excel, Python) listed by alumni from each college. For the average college, we observed 1,150 profiles per skill. (A great advantage of using LinkedIn data is the large sample size.) We obtained data for 2,164 colleges representing profiles for 2.5 million U.S. residents who attended college. By comparison, Academically Adrift surveyed 2,300 college graduates.

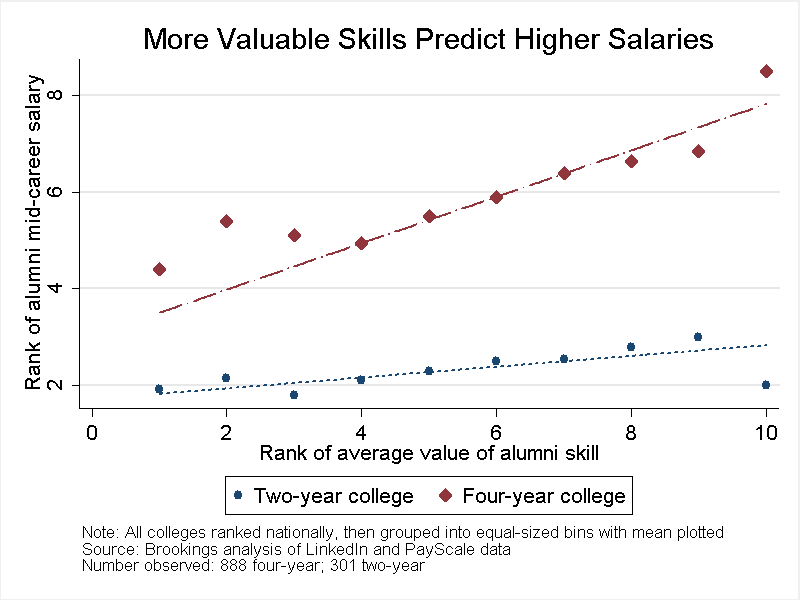

Alumni with more valuable skills earn higher salaries

Measured at mid-career (meaning at least 10 years of working), salaries tend to be much higher for alumni who list high-value skills on their resumes. Earnings go up by an average of $2,600 for every decile of skill. Our more detailed empirical work shows that skills predict higher earnings even after controlling for math test scores on the ACT and SAT, as well as other student characteristics like family income.

Cal Tech graduates list the highest-value skills (e.g., Matlab, Python, C++, algorithms, and machine learning) and typically earn $126,000 at mid-career. Other four-year schools with high-value skills and high salaries include Harvey Mudd, MIT, the Polytechnic Institute of New York University, and the Air Force Academy.

Earnings data from two-year colleges are not as widely available, and the correlation with alumni skills is weaker, but alumni from those schools also seem to benefit from higher skills training. Top schools include the Pittsburg Institute of Aeronautics, Spartan College of Aeronautics and Technology (Tulsa, Okla.), Coleman University (San Diego), Hondros College (Columbus, Ohio), and SUNY College of Technology at Alfred.

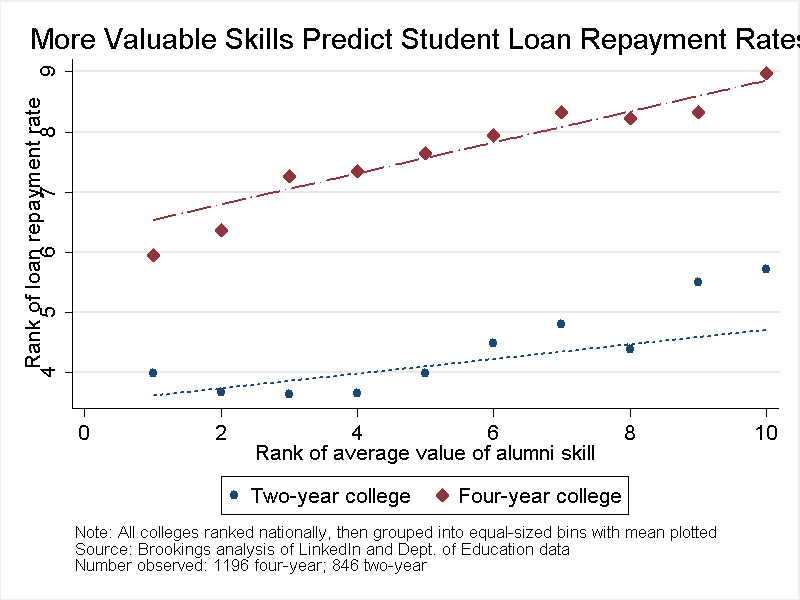

Alumni with more valuable skills have higher loan repayment rates

As an alternative to mid-career earnings, we also analyzed how skills predict the ability to make student loan payments immediately after graduation. Here too, more valuable skills translate into labor market success. For example, not a single Harvey Mudd attendee between 2009 and 2011 defaulted on his or her federal loans within three years of leaving. Repayment rates average 95 percent for four-year colleges in the top 10 percent for alumni skills but 87 percent for those in the bottom 10 percent. For two-year colleges, repayment rates are uniformly lower, but colleges offering higher-value skills still have significantly higher repayment rates than those that do not.

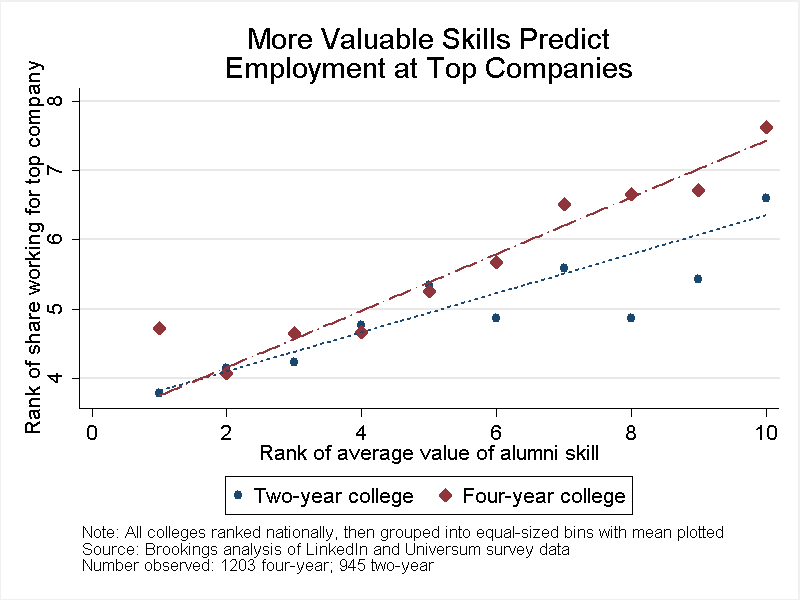

Alumni with more valuable skills are more likely to work for top organizations

Another outcome measure is whether alumni work for a desirable company or organization. LinkedIn lists the 25 enterprises that employ the most alumni from each school. To quantify the value of working for a given entity, employers were coded for desirability with data from a 2014 survey of 46,000 U.S. college students in 329 universities, developed by Universum, a corporate marketing intelligence company. A total of 212 employers, including government agencies, made it onto a top 100 list for at least one group of student majors. The most desirable employers across majors were Google, Disney, Apple, Microsoft, the FBI, Nike, NASA, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Peace Corps, and Facebook.

For the top 10 percent of four-year colleges on alumni skills, half of LinkedIn alumni profiles indicate employment at one of the 212 top-rated companies, compared to just one in four for schools in the bottom 10 percent. For two-year schools, nearly two in five alumni (37 percent) of top-tier schools by skill worked for a top company, versus one in five alumni (21 percent) of bottom-tier schools.

For placement at Google specifically, Harvey Mudd has the highest rate—2 percent of all alumni—followed by Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, Caltech, and MIT. Almost all of the colleges with the highest placement rates at Google are in the top 20 percent of alumni skills, including liberal arts colleges like Swarthmore, Pomona, Claremont, McKenna, and Williams.

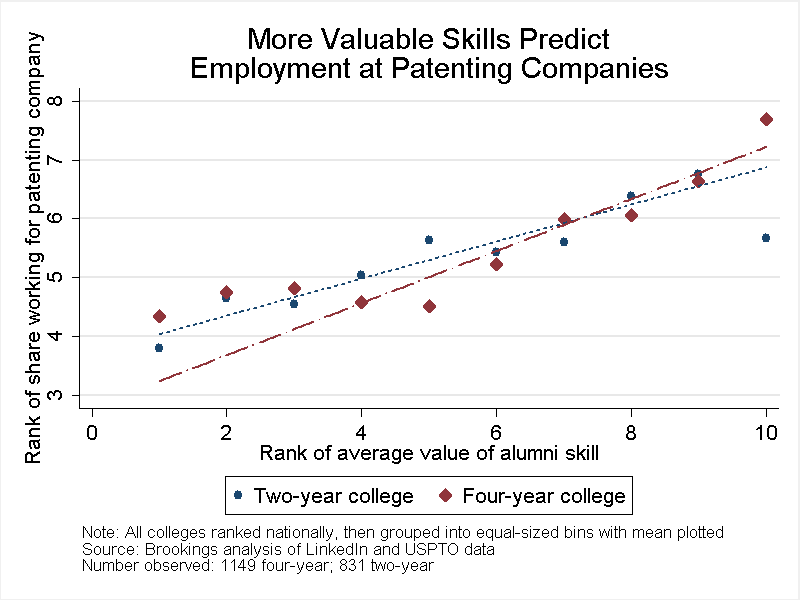

Alumni with more valuable skills are more likely to work for innovative organizations

Workers who contribute to the creation and development of new, valuable products can lift the living standards of people around the world. Companies that patent are more likely to be creating these sorts of advanced industry products, and 843 entities, including universities and government agencies, own at least 40 patents granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in 2014.

Four-colleges that graduate alumni in the top 10 percent by skill are twice as likely to have graduates working at a top patenting organization than are colleges in the bottom 10 percent (3.3 versus 1.6 percent). Likewise, graduates from two-year colleges are about twice as likely to be working for a patenting entity if their school is in the top 10 percent compared to the bottom (1.9 versus 0.9 percent).

Schools with high placement rates at patenting entities include those listed above, as well as less the U.S. Naval Academy, Lawrence Technological University, the Stevens Institute of Technology, Santa Clara University, Brazosport College, Mount Mercy University, University of Texas-Dallas, the Missouri University of Science and Technology, and San Jose State University.

How to judge colleges

Earnings and other economic outcomes should not be equated with social value, and there are plenty of jobs and professions—child care, teaching, social work—that pay modestly but are nevertheless highly valuable to society. Colleges that specialize in this training or instill even moderately valuable skills in the least academically prepared students may be socially important institutions even if their alumni frequently are less affluent.

Nonetheless, earnings clearly matter privately and socially, as does work that supports innovation and highly productive advanced industries. Many colleges offer programs of study in fields that appear to have almost no market value—nor even any social value since the knowledge acquired is never put to use, at least through paid employment. In this sense, how well colleges instill highly valuable skills and prepare students to contribute productively to the economy should be an important consideration when evaluating schools. Colleges that do this for the students least likely to otherwise succeed are offering an even more beneficial service, as we have discussed in our value-added college research.

Correction: A previous version of this post showed graphs which reversed the label on 2- and 4-year colleges. The graphs have been corrected.

Commentary

Op-edSkills, success, and why your choice of college matters

July 8, 2015