For city and state leaders who are looking to create economic opportunities by increasing jobs or community assets, the solution can be found in supporting the growth of Black-owned businesses. From 2017 to 2022, the number of Black-owned businesses surged, representing over half of all new employer businesses. In 2022, Black-owned firms with at least one employee (known as “employer” firms) added $212 billion in revenue to the economy and paid over $61 billion in salaries.

Yet despite this growth, systemic underinvestment in Black entrepreneurs creates barriers across all stages of business growth, from accessing credit for startups to hiring employees and growing revenue. Nationally, while ownership rates of non-employer businesses are broadly similar across demographic groups, the proportion of Black-owned employer businesses is substantially lower than the share of the Black population. While 14.4% of the U.S. population identifies as Black or African American, only 3.3% of all employer businesses are owned by them.

Achieving greater racial equity in employer business ownership advances goals of wealth creation and broader economic development. According to data from Gallup, Black-owned employer businesses earn close to five times the revenue of Black-owned non-employer businesses. Moreover, the same study demonstrated that owners of employer firms report greater subjective well-being and, unsurprisingly, greater total net worth. Employer businesses ownership, as much as it is a driver of economic growth, is also a pathway to growing intergenerational wealth that could close race-based wealth gaps.

This report assesses barriers for Black entrepreneurs and business owners at three crucial stages of business development: 1) as a startup; 2) the transition to an employer firm; and 3) sustaining growth as an employer firm. To understand the barriers that Black business owners face, this report analyses data on employer and non-employer firms from the Federal Reserve Small Business Credit Survey from 2020 to 2024, Small Business Administration data from 2017 to 2025, and the Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey and Nonemployer Statistics from 2022. In combination, these datasets provide information on the demographics, revenue, lending, and operational experiences of American businesses.

After assessing these barriers, and in light of recent challenges to lending practices that target Black-owned businesses, this report recommends policy changes that would help sustain the growth in Black-owned businesses in a more turbulent policy context.

Starting a business: How racial wealth gaps, low homeownership rates, and a lack of credit access inhibit Black business creation

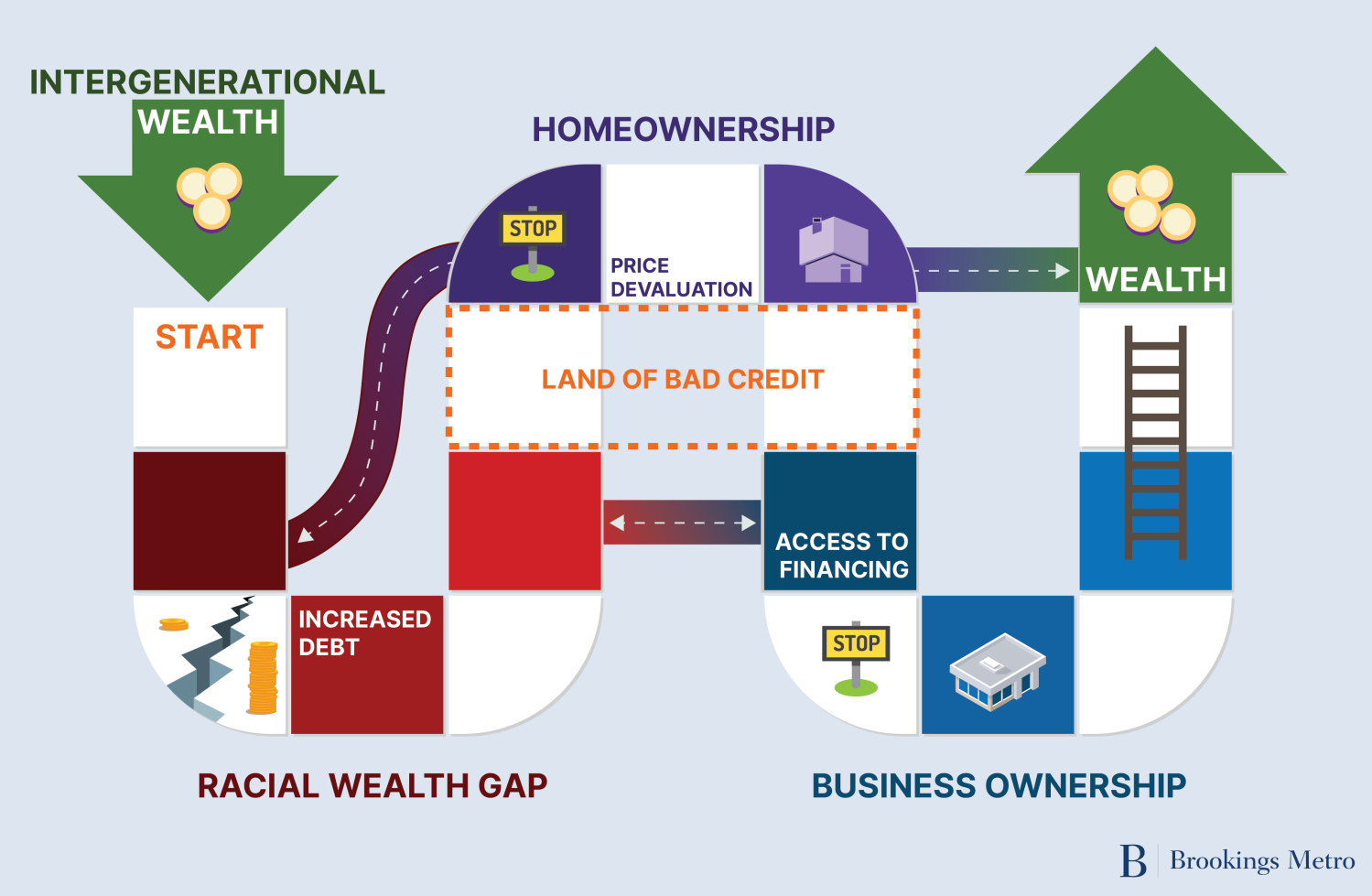

The first major hurdle for Black entrepreneurs in starting their business is a lack of startup funds, equity, and collateral—a result of the racial wealth gap. Research shows that a foundational barrier to business creation for Black Americans is low wealth, and more importantly, less access to intergenerational wealth. In 2022, for every $100 in wealth held by white households, Black households held only $15. The relative lack of collective wealth Black Americans hold compared to the wealth of other demographic groups means that Black Americans have lower rates of homeownership (a crucial asset for securing business loans) and higher levels of debt, which leads to higher interest rates and makes business loans more expensive or inaccessible.

For many Americans, homeownership provides the capital to start a business, as entrepreneurs who lack cash on hand (another byproduct of wealth disparities) can often borrow against their home equity or use their homes as collateral. According to a Small Business Administration (SBA) study, one-third of Black entrepreneurs used personal assets such as homes to secure funding—relatively on par with other racial groups. Yet the lack of intergenerational wealth along with local and national policies that systematically denied and often violently prevented Black homeownership mean that Black Americans are less likely to own a home compared to the overall population. The latest U.S. census estimates reveal that 44.4% of Black Americans own a home, compared to 65.2% of Americans overall.1 Furthermore, homes in majority-Black neighborhoods are systematically undervalued by a cumulative total of $162 billion, meaning Black homeowners looking to secure business loans will, on average, have less equity compared to their non-Black counterparts.

Moreover, because Black Americans have lower levels of wealth, Black entrepreneurs typically have higher levels of debt, making it harder to acquire a loan to purchase property or start a business. A disproportional number of Black households are in debt: 18.9%, compared to their population share of 14.4%. Student loans are a major driver of this debt, with Black student loan borrowers holding 36% of student loan debt at an average of $53,000, according to the latest Survey of Consumer Finances.

The impacts of low intergenerational wealth and homeownership and higher rates of debt show up prominently in credit scores, which are important for access to loans and determining repayment rates. On the surface, credit scoring is a race-neutral system; race does not appear on a credit report, nor do addresses or ZIP codes that could indicate the racial demographics of a neighborhood. Yet racial gaps in credit scores are persistent over time and place, and Black-owned startups receive lower credit scores than the overall population of business owners. For example, 26% of Black-owned startups are categorized as having high credit risk, compared to 16% of startup owners overall.

Credit disparities by race are primarily due to how credit scores are calculated. For example, credit scoring models favor homeownership over renting because mortgages establish a debt repayment history that renting does not. In this way, the racial homeownership gap systematically contributes to the credit score gap. Debt also influences credit scores, especially outsized levels of student loan debt. A nationally representative 2023 Federal Reserve survey of small businesses found that the second most common financial challenge for Black-owned startups was credit availability (52%), just behind “paying operating expenses” at 53%.

Systemic racism in credit scoring at the community level leaves Black entrepreneurs with a higher likelihood of receiving subprime loans, which demand higher interest rates and result in those entrepreneurs incurring more debt. Young adults (between 25 and 29) in Black-majority neighborhoods have a median credit score of 582, compared to 644 in majority-Latino or Hispanic neighborhoods, and 687 in majority-white neighborhoods. Credit scores below 650 can make it difficult to qualify for an SBA loan, and scores below 600, considered “subprime,” substantially increase the total cost of the loan. For example, business owners with a subprime credit score looking to purchase a $10,000 used car for their business can expect to pay $3,000 more in interest over four years than borrowers with prime credit scores.

In terms of business creation, systematic gaps in credit scores based on race, coupled with continued discrimination in lending, result in higher rates of subprime loans and comparatively high interest rates for Black business owners. For example, even comparing firms with relatively high credit scores, Black-owned businesses were half as likely as white-owned counterparts to receive all of the financing they sought. These compounding factors of de jure and de facto racism mean Black entrepreneurs are more likely to incur debt, less likely to have on-hand cash reserves, and are therefore less likely to start a business or more likely to prematurely close.

Launching and maintaining a startup in the U.S. is difficult: 21.5% of private sector businesses in the U.S. fail in the first year, and 65.1% close within 10 years of opening. The odds for Black entrepreneurs are even starker. In 2018, 96% of Black-owned firms did not survive the startup phase.2 Worse, the consequence of business failures is downward wealth mobility for Black Americans.

Paradoxically, the relationship between business ownership and intergenerational wealth is somewhat circular. The racial wealth gap creates compounding factors that limit business ownership, and the business ownership gap limits Black wealth accumulation. Recent economic modeling shows that the lower rates of Black-owned employer businesses historically explain most of the nation’s current wealth disparities.

Transitioning from a sole proprietor to an employer firm: Accessing credit and relying on non-traditional lenders

Many new businesses often have no employees and are run by one person—classifying them as “sole proprietorships”—before growing to a size that allows them to hire. Sole proprietorships, the easiest to establish and most common type of business, include freelance writers, accountants, and personal trainers. These businesses represented 84% of total U.S. businesses in 2022, and also represent the vast majority of Black-owned businesses: around 96% nationally. According to SBA data from 2023, 58% of Black sole proprietorships were less than five years old.

Young Black sole proprietorship owners in particular have some of the lowest rates of firm survival, closing their new businesses at faster rates than their Latino or Hispanic and white counterparts. Studies show that 22% of new businesses owned by Black Americans under 35 years old closed after just one year, compared to 15% of Latino or Hispanic-owned firms and roughly 13% of white-owned firms.

Yet the drive to expand and grow Black businesses is evident. In 2023, Black sole proprietors were more likely to seek financing for the purpose of business expansion than their Latino or Hispanic and white counterparts. Additionally, 56% of Black sole proprietors had the goal of hiring employees in the next year, more than any other racial or ethnic group surveyed.

Given the extensive systematic barriers in starting a business, additional loan approval rates for Black entrepreneurs are lower than the national average. In 2021, just 13% of Black-owned businesses were likely to receive financing they applied for. In comparison, Latino or Hispanic- and Asian American-owned firms received financing in 20% and 31% of cases, respectively, while white-owned businesses received financing in 40% of cases. Black business owners are also more likely than white business owners to report unfair treatment when acquiring loans. According to data from Gallup, 17% of Black business owners said they experienced discrimination in the past five years, compared to 6.8% for all owners and 3.8% for white owners.

Figure 1 shows the share of SBA loans approved (by number and loan amount) for Black entrepreneurs. These shares increased on average from 2017 to 2025, but remained low compared to the share of the Black population. In 2025, 6.5% of Black-owned business owners were approved for a loan, up from around 4% in 2017, but below the high of 8% in 2023.

With Black business owners having lower-than-average credit scores, nontraditional financing sources such as credit unions, community development financial institutions (CDFIs), and online lenders offer important alternative avenues to securing capital. For over a century, community leaders have created alternative financial institutions to fill gaps in home and business loans to Black Americans overlooked by traditional banks. In 1920, the first Black-serving credit union opened, and for decades credit unions were seen as a tool of economic justice, with many Black-owned credit unions opening in Black neighborhoods.3 In 1994, Congress created CDFIs to catalyze home, business, and real estate lending in economically disadvantaged communities. In the modern era, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, online lending through venture capital and fintech companies emerged as another important source of small business finance—one disproportionately used by Black business owners according to recent survey data.

However, these alternative financial institutions also come with their own challenges, including higher interest rates, unfavorable repayment terms, and longer wait times. Figure 2 shows that close to 40% of Black sole proprietors stated that online lenders offered interest rates that were too high, compared to 14% of Black business owners who applied for loans with CDFIs and credit unions. As previously discussed, Black entrepreneurs already receive higher interest rates more often than other racial groups.

Despite the challenges, Black sole proprietors seek out these alternative lenders as a means to combat systemic barriers. Over half of all Black sole proprietors stated they applied for loans at credit unions, CDFIs, or online lenders because they provided a chance of being funded. Of those that applied to credit unions, 63% made this claim, and 38% stated they applied because no collateral was required. And despite long wait times and unfavorable repayment terms at CDFIs, 58% of Black sole proprietors sought funding at these institutions because they believed they had a better chance of being funded, while nearly half stated they applied due to more preferable interest rates. Black sole proprietors applied for loans at online lenders 45% of the time because they were denied by other lenders, and 40% because of the speed of funding decisions.

Collectively, these barriers mean that Black-owned sole proprietors are more often discouraged from applying for loans to grow their business. In 2023, for example, 39% of Black sole proprietors who didn’t apply for any financing did so because they felt discouraged. An overwhelming 61% of those discouraged to apply reported it was due to their financial position, while others listed strict lender requirements or because they had previously been denied loans. Another 31% of Black sole proprietors did not apply for loans because they were debt averse.

As reflected in these data, Black business owners’ desire to expand is often thwarted by the compounding impacts of wealth and homeownership disparities that carry over into low credits scores and difficulties attaining business financing. The financial sector should not take these approval gaps and systematic challenges lightly, as they artificially restrict the scale of Black businesses and, in the process, diminish lending opportunities for financial institutions themselves. Above all, the barriers Black entrepreneurs face limit the dynamism of the overall economy and undermine worker and community prosperity. If the share of Black employer businesses reached parity with the share of the Black population, cities across the country could see as many as 757,000 new businesses, and with them, 6.3 million more jobs and an additional $824 billion in revenue circulating in local economies.

Sustaining and growing an employer business

Sustaining and growing an employer business —the next stage of Black business ownership—presents a new set of operational and financing dynamics. At the end of 2023, 46% of Black-owned employer businesses were more likely to be operating at a loss, compared to just 35% of all employer businesses. To cover these financial gaps, Black-owned employers are more likely to use personal funds; 67% of Black employers surveyed stated that they used personal funds to cover business shortfalls, compared to 55% of employers overall.

In 2024, fewer Black-owned firms reported operational challenges compared to other demographic groups, yet challenges remained. Table 2 shows that around 56% of Black-owned employers reported reaching customers and growing sales as their primary operational challenge, which is comparable to the overall proportion of 57%. This challenge is yet another byproduct of structural racism, as businesses in majority-Black neighborhoods are shown to receive fewer Yelp reviews and lower ratings than comparable businesses in non-Black-majority neighborhoods, causing them to lose out on $1.3 billion to $3.9 billion in revenue per year. Meanwhile, substantially fewer Black-owned employers identified challenges with hiring or supply chains compared to other firms.

Rather than challenges in successfully operating a business, the barriers that Black-owned employers face stem from debt and access to financing. Credit risk remains high for Black employers compared to employers overall, carrying with it the impacts of higher interest rates, especially at traditional banks. Similar to Black-owned sole proprietorships, 44% of Black-owned employers listed a low credit score as a reason for loan denial.

Due to challenges accessing capital at banks, Black employer business owners also often turn to other financing sources. From 2019 to 2023, the number of CDFIs grew by 37%, and from 2018 to 2023, CDFI assets tripled to $452 billion, with nearly 70% of the asset growth coming from newly certified institutions. For Black employers, CDFIs are a popular financial alternative. In 2024, 20% of Black employers applied for loans with CDFIs, compared to 6% of employers overall; Black employers reported that they thought they were more likely to get funding through these institutions. Additionally, 43% of Black employers said they were recommended to apply to CDFIs, and 35% said they applied because of the interest rates offered.

Another important source of funds to sustain Black-owned businesses are government contracts, which tend to be more reliable and stable than other customer bases. Yet Black- and other minority-owned businesses are still awarded contracts at a lower rate than other demographic groups. In 2024, data from the SBA indicated that roughly 1.5% of the federal government’s $637 billion contracting budget went to small Black-owned businesses. In contrast, 72.5% went to large corporations and 16.6% to non-minority-owned small businesses. This disparity, along with long-standing gaps in wealth, debt, and access to credit, are barriers to growing the share of Black-owned employer businesses to equitable numbers.

Policy recommendations to remove barriers for Black-owned sole proprietorships and employer businesses

Spurned by drastic reversals in federal policy and spending cuts following the election of the Trump administration, there are fewer opportunities for Black-owned businesses to access capital through national programs such as the Minority Business Development Agency. Moreover, the administration has implemented policies and executive orders that are challenging the legality of mission-based investors who use race as a targeting mechanism or are motivated to address structural racism. In this new political context, it is worth asking what types of policy changes that don’t use race or ethnicity as a targeting mechanism could support continued growth in Black-owned sole proprietorships and employer businesses. Discussed below are four pathways in which policy changes could have the most impact.

Address the root causes: Closing wealth and homeownership gaps to grow the middle class

At the root of barriers to Black-owned business creation and growth are wealth and homeownership gaps and disproportionate levels of debt. Because of these gaps, policies that provide opportunities for renters to purchase housing and others that lower the likelihood of future debt for children born into poverty have a disproportionate impact on Black Americans and would help reduce the race-based gaps in wealth that undermine business creation and growth.

Policies that create avenues for homeownership for low- and middle-income families support growth in Black-owned businesses, as mortgages provide a source of capital for business creation. This could include, for example, first-time homebuyer assistance that offers interest-free or low-interest loans to families purchasing their first home. Additionally, acting to remove racial biases in home appraisals and property tax assessments by standardizing the accreditation process for evaluators and providing more transparent appraisal metrics would help minimize the wealth loss for Black homeowners.

Policies that rectify the damage of intergenerational wealth inequality and decrease personal debt would allow more opportunities for Black entrepreneurs to access personal and institutional capital to start and sustain their businesses. Baby bonds, for example, proposed by economist Darrick Hamilton, would provide every child born into poverty with a publicly funded trust account at birth. This seed capital would replicate the intergenerational wealth transfer that is common among wealthy—and often white—families, growing at a fixed rate to be available upon adulthood for investments such as buying a home and starting a business. Federal and state policy could also aim to reduce the debt low-income households and families in poverty hold. For example, providing greater access to tuition-free public universities would decrease levels of student debt—one area that is increasing the racial wealth gap between Black and white households.

Reduce racial biases in credit scoring practices

Existing credit scoring systems exacerbate race-based divides in access to capital and wealth, and moreover, do not accurately predict risk. Current credit scoring practices prioritize FICO scores while disregarding other factors such as payment history for rent and utilities, which can provide a fairer and more transparent indication of risk. Expanding underwriting criteria would help reduce the influence of race-based gaps in wealth and homeownership on credit scoring, and thus the influence of racial biases in loan denials.

Enacting policies to address ongoing discrimination in lending decisions would also help reduce race-based gaps. Recent research demonstrates that if credit scores for Black-owned businesses were treated in the same way as scores for white men, those businesses’ credit lines would double. A clear area for reform is to make the system more transparent and accessible to individuals and business owners. Empowering Black business owners with higher-quality data would help reduce information asymmetries in the market and lessen the potential for errors in credit scoring.

Grow pathways to access capital by supporting alternative financial institutions

Given the barriers they still face in accessing affordable credit, Black business owners would benefit from policies that expand capital access. This would include, for example, investing in institutions that Black business owners trust and are already using, such as CDFIs and credit unions. CDFIs overwhelmingly benefit Black-owned businesses and Black communities, approving applications at twice the rate of large banks. In lieu of federal support, local governments and community development organizations can play a leading role in engendering change. For example, Invest Detroit has channeled investment into strategic commercial corridors in the city’s Black-majority communities without displacing residents.

In addition, policies that support and expand access to credit programs and government contracts for small and midsized enterprises would also support Black-owned businesses. A prime candidate is expanding special purpose credit programs (SPCPs), which can be offered by banks, nonprofits, and private investors. These programs, authorized under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), help creditors fund social needs that benefit disadvantaged groups and address inequities by relaxing or altering loan requirements, such as accepting applicants with a lower minimum credit score. However, few lenders have taken advantage of the ECOA, and notably, the Federal Housing Finance Agency terminated Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s use of SPCPs for home loans in March 2025, creating a chilling effect and uncertainty for business lenders.

Increase accountability for lenders and contracts by mandating public data

Finally, while available data on approval rates for businesses by race and ethnicity are limited, mandating transparency in the lending environment through state and federal reforms would allow for business owners and lenders alike to identify gaps and find solutions. This could include, for example, mandating that banks publish annual data on loan approvals by race and ethnicity.

Relatedly, while the federal government has published data on contracting since 2007 and began disaggregating these data by race and ethnicity in 2021, many corporations still do not. Fortune 500 companies, which represented over $18 trillion in revenue in 2023, are also major procurers of services from small and midsized firms. Private action to increase transparency in contracting would hold companies accountable to equitable lending practices.

Conclusion

Earlier this month, the Juneteenth holiday commemorated Black Americans’ freedom from enslavement, first celebrated on June 19, 1866. Just a year later, the recorded number of Black-owned businesses was 4,000.4 Today, there are roughly 4.6 million Black-owned business in the United States, and each one stands as a testament to the power of Black Americans who, 160 years after the final declaration of emancipation, continue to prosper and fight for the right to do so in the face of systematic barriers. Taking actions that address these barriers—through corporate, bank, and governments reforms—would not only benefit Black Americans, but the nation as a whole.

The relationship between wealth and business ownership is circular. Low intergenerational wealth limits business creation, which reduces the potential for future wealth-building. Interventions that break this cycle could reduce race-based gaps while also unlocking a wave of business creation that will ultimately benefit future generations of Americans.

-

Footnotes

- These data are according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey 1-year estimates, regarding the total population and respondents who identified as Black alone or in combination with one or more other races.

- Although not defined in the study referenced, Federal Reserve small business surveys define “startups” as firms that are two years old or younger. See: https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/categories/startup-firms

- See also “The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap” by Mehrsa Baradaran (148-149).

- Melvin L. Oliver and Thomas M. Shapiro, “Black Wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality” (New York: Routledge, 2006), 48.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).