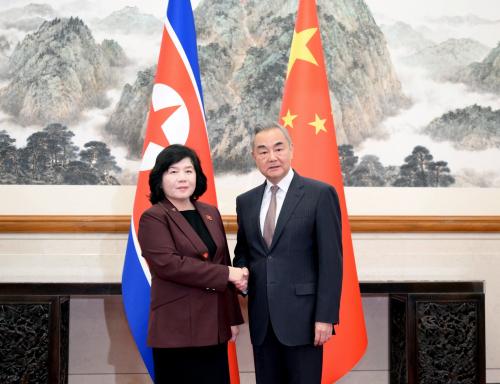

In meetings with Chinese officials and analysts before the Singapore summit between President Trump and Kim Jong-un, I encountered a recurring question: Would Trump accept incremental gestures of goodwill from North Korea, perhaps as stepping stones toward eventual denuclearization? Early indications suggest that my Chinese counterparts were prescient in foreshadowing what would occur at the Singapore summit, and since.

In the four-point declaration that the two leaders signed in Singapore, they listed areas of agreement as:

- A shared commitment to establish a new U.S.-North Korea relationship;

- Working to build a lasting and stable peace regime on the Korean Peninsula;

- Working toward the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula; and

- Recovering remains of American soldiers in North Korea.

In other words, the sequencing of the joint statement gave priority first to improving bilateral relations, and then to denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula.

President Trump appears to have leaned into this logic. He has stressed the singular importance of his personal relationship with Kim Jong-un, suggested that improving leader-level and state-to-state relations will reduce the threat from North Korea, and assured the American people that the nuclear problem has been “solved.”

Such an arrangement works well for Kim Jong-un, too. Kim has agreed to take visible steps to improve U.S.-North Korea relations, while leaving ambiguous whether he is committed to abandoning his nuclear and missile programs.

If Kim’s goal is to string along the United States as he continues covertly to develop his nuclear and missile inventory, he has many cards to play with Trump. These include returning the remains of American soldiers that perished in North Korea during the Korean War, setting up military hotlines between Washington and Pyongyang, establishing permanent diplomatic liaison offices in both capitals, conducting cultural exchanges, granting special access to Western journalists to report on changes underway in North Korea’s economy and society, and invigorating efforts to achieve progress on a peace treaty to conclude the Korean War.

All of these potential steps would be positive in their own right. There will be a strong impulse within parts of the United States government to embrace such steps as proof that President Trump’s engagement is yielding gains, improving U.S.-North Korea relations, and lowering the risk of conflict. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo should be prepared to welcome such steps, but not as a substitute for progress in achieving the complete, verifiable, irreversible disarmament of North Korea’s illicit programs.

Pompeo must remember that North Korea wants to shift the focus of the discussion away from its weapons programs and toward highlighting North Korea’s improving relations with the outside world. Pyongyang wants to normalize relations with the United States and others without giving up its nuclear weapons and fissile material. If Pyongyang succeeds, it will gain de facto recognition as a nuclear power, a long-sought objective of the Kim family.

The recent news cycle in the United States illustrates why succumbing to North Korea’s playbook could prove so dangerous for American national security. U.S. media outlets have reported in recent days that North Korea is upgrading its official nuclear enrichment site at Yongbyon, stepping up enrichment at two or more secret sites beyond Yongbyon, and continuing to develop and produce solid fuel engines for missiles and mobile launch vehicles for its ballistic missiles. If even a fraction of these reports are true, they would call into question whether Kim is committed to exchanging his nuclear and missile programs for a better future for him and his people.

Secretary Pompeo reportedly will have an opportunity in the coming days to engage directly with Kim Jong-un and members of his inner circle. He should use that opportunity to stress that there is no way to realize the potential of U.S.-North Korea relations—and for North Korea to be accepted into the community of nations—if Pyongyang continues to improve its ability to target the United States and its allies with weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Pompeo needs to focus Pyongyang on the urgent need to halt production of highly enriched uranium and plutonium, provide a full and complete inventory of its WMD and missile programs, allow inspectors entry to verify North Korea’s claims, verifiably dismantle the infrastructure used to produce WMD and long-range missiles, and ultimately send existing fissile materials and nuclear warheads out of the country, as my Brookings colleague Michael O’Hanlon has argued. Pompeo’s task will be made easier if he is in a position to inform Pyongyang what incentives will become available to them if they go down this path, and when.

President Trump made a bet in Singapore that he could translate a personal relationship with Kim Jong-un into improved U.S.-North Korea relations and denuclearization. He argued that no other approach has worked, so why not give his a try. Recent reports of nuclear production activity in North Korea are calling into question whether Kim Jong-un shares a similar investment in such an approach. The only way to find out will be to keep the focus on North Korea’s WMD and missile programs, and not allow symbolism to serve as a substitute for concrete steps toward denuclearization.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

On North Korea, don’t get distracted by shiny objects

July 3, 2018