Migration is a very old phenomenon in world history; much older than trade and capital flows. Scientists believe that the first massive migration of modern humans happened between 80,000 and 60,000 years ago, from Africa to Asia. In modern history, migration has typically been the subject of heated policy and political debates, even becoming the raison d’etre for hundreds of organizations worldwide.

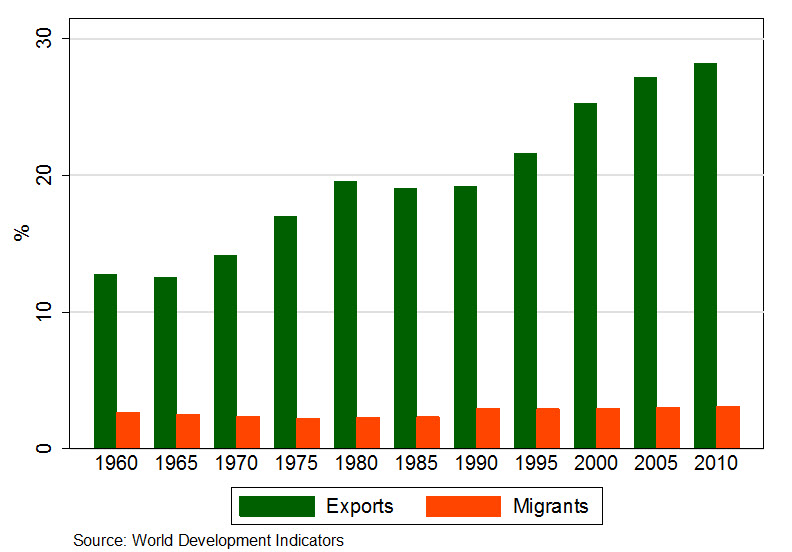

To the casual observer, one might think we are experiencing another migration explosion. But in fact, migration today remains somewhat steady, in relative terms. According to the World Development Indicators (see Figure 1), in 1960, migrants made up 2.63 percent of the global population, whereas exports of goods and services accounted for 12.7 percent of global GDP. By 2010, these numbers were 3.11 percent and 28.19 percent, respectively.

Figure 1 – World’s Migrants % of Population and Exports % of GDP

As Michael Clemens from the Center for Global Development points out in a recent paper, economic research on skilled migration has for the most part focused on the “bad news” of it all, with some emphasis on the “brain drain” phenomenon and its short-term effects. For instance, how the home countries of the migrants lose, and how plausible wage depression hits the receiving country.

There is extensive literature on the extent to which wages in the destination country are affected by a flow of migrants, but it is still open to debate. Recent work by Stanford’s Ran Abramitzky, UCLA’s Leah Platt Boustan, and Katherine Eriksson from Cal Poly, using historic panel data on migration to the United States, shows two interesting findings. First, migrants arriving from countries with above-median wages held higher paid occupations than U.S. natives upon arrival, and vice versa. Second, the study finds that this original gap in salaries is maintained for at least 30 years. While these results do not directly speak to how the salaries of natives were affected by an influx of migrants, they do suggest migrants are paid based on skills gathered during their pre-migration careers. We could extrapolate further and say that the migrants’ skills were different from those of natives, because otherwise salaries of migrants and natives would have been the same upon their arrival, and even if not, we would see a convergence over time. Thus, migrants bring with them skills that are remunerated accordingly. Then the natural question to follow is what are the long-term benefits of this influx of skills to societies with a higher propensity to attract migrants?

Recent research has looked at the positive impact of migration on longer-term processes. For instance, a growing literature pioneered by UCSD’s James Rauch, shows the importance of migrants and their networks in reducing transaction costs for bilateral trade and foreign investment, which is considered a fuel for growth and development for both countries involved (in a recent work, Christopher Parson and Pierre-Louis Vezina address this same question with a neat natural experiment). My work, together with Paris School of Economics’ Hillel Rapoport, shows that migrants play an important role in transferring knowhow and knowledge that translates into sectorial productivity increases in both the migrants’ origin and recipient countries, which results in more diversified export baskets. Migrants also play an important role in the flow of ideas and in stimulating innovation, as Bill Kerr and Prithwiraj Choudhury from Harvard Business School have shown in their work. See Clemens’ piece for many more examples.

Now, these are only a few examples of the long-term benefits of migration that have been researched that, possibly, outweigh potential short-term disadvantages. Yet, in spite of these benefits, migration is still a controversial topic in theory and in practice, it remains a very small phenomenon as compared to other flows (e.g., capital and goods). As Harvard’s Lant Pritchett points out in his book, “Let Their People Come: Breaking the Gridlock on Global Labor Mobility,” international labor regulations hinder migration flows, which, ironically, could be a crucial tool for economic development.

As I mentioned in a recent blog post, if we take the business world as an example (something economists love to do), short-term migration is an important tool for productivity improvements. Large and established firms commonly cover worker training abroad; small firms are unable to do so because the externalities are too high. This can help us understand that there are plenty of market failures that would justify smart policy interventions linking the acquisition of knowhow and knowledge through short-term migration programs that likely would have an impact on labor productivity. Tackling them would advance the diffusion of knowledge and, with it, the development of nations.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Migration and the gains from brain drains for global development

August 24, 2015