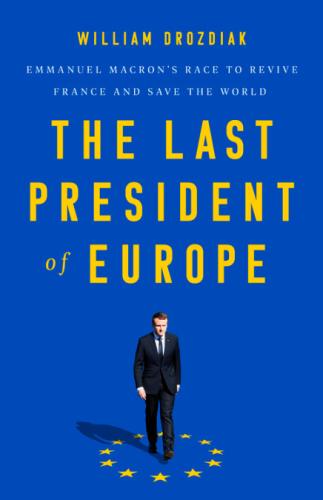

On April 24, Emmanuel Macron was reelected as president of France, beating far-right challenger Marine Le Pen in a runoff for the second time. After what briefly appeared to be a tight race in early April — with one poll putting Le Pen within two points of the incumbent president — Macron’s victory came as a relief for many.

Yet compared to 2017, the gap between the two candidates has narrowed: Macron received 18.8 million votes this year, two million less than in 2017, while Le Pen gathered 13.3 million, almost two million more than five years before. The difference between their vote shares has been nearly halved. Does this mean support for Le Pen’s nationalist populism is on the rise in France? That’s only part of the story.

Three larger trends have been confirmed. First, far-right ideas have gained traction by mainstreaming, not by radicalizing. When Le Pen’s extreme platform came into view, it failed, once again, to be endorsed by voters. Second, the left-right divide in France is durably weakened: new fault lines are emerging, geographically and politically, between the center and the periphery. Third, Macron’s presidential momentum is likely to be short-lived. Unless he secures a large governing majority in the upcoming parliamentary elections, his second term is likely to be marked by sustained challenges from the left and from the far right. 2022 conveyed contradictory lessons, and it remains to be seen if and how Macron can adapt his unique brand of centrism.

Mainstreaming the far right

French presidential politics are played in the center. Because the presidential election’s second round is a duel between two candidates, each must seek to gain an absolute majority of voters. Marine Le Pen has long understood that she needed to overcome the fundamental aversion that her candidacy elicited to advance to the final round. To this end, she has sought not to activate the most radical factions of her camp, but rather to appear palatable to a majority of voters.

Le Pen campaigned for the 2022 election on the cost of living rather than immigration and on civil liberties rather than national identity. In an effort to break down ideological barriers, much as Macron does, she declared her disinterest in the idea of left and right in politics. The strategy worked: between the first and second round, she gained not only 17% of far-left Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s electorate but also 18% of the center-right Valerie Pécresse’s voters.

However, Le Pen’s metamorphosis is far from complete. Benefiting from the presence in the race of a much more visibly extremist candidate, Eric Zemmour, she was able to maintain ambiguity over her radical platform through the first round, sounding more populist than nationalist. It allowed Le Pen to garner sympathies and to suggest to voters that, rather than being disruptive, she would benefit working-class and rural French people. Tellingly, in February 2022, almost twice as many voters believed that their personal situation would improve if Le Pen was elected (27%) as with Macron (15%).

However, in the two weeks between the first and second round, Le Pen’s platform and proposals finally came under media scrutiny and under political fire from a wide spectrum extending from far left to center right. Her radical ideas, such as banning the headscarf in the public sphere, or establishing a “national preference” for public services, were once again publicly discussed. It woke up the “republican front,” a coalition of French voters who recognized that, while they did not necessarily want to cast a vote for Macron, they still needed to prevent the far right from acceding to the presidency. Le Pen’s 10-year “de-toxification” strategy has come a long way, but, once again, failed.

New fault lines

The weakening of the formerly defining cleavage in French politics between left and right, theorized and exploited by candidate Macron five years ago, has been confirmed in this election. The candidates of the two mainstream parties which had dominated the French party system until 2017 received abysmal scores (4.8% for Pécresse of the center-right Les Républicains and 1.8% for Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, of the center-left Socialists). Instead, new divisions are emerging.

Overtime, Macron has come to represent the center, not only politically but also geographically, while Le Pen’s camp has come to embody the periphery. The president received a greater share of votes from executives than he did from workers, and from French voters with higher education diplomas than not. Polls show that those who are satisfied with their lives overwhelmingly (69%) voted for Macron, while close to 80% of those who are unsatisfied voted Le Pen. The same patterns hold for self-identification: almost 80% of those who feel “at ease, or privileged” voted Macron, whereas those who consider themselves “underprivileged” chose Le Pen (65%). 70% of French voters in large cities chose Macron (up to 80% in greater Paris), while Le Pen achieved her best scores in rural France (50%) and small towns distant from large cities (46%), as well as peri-urban areas (45%). It’s not just Le Pen who resonates with the periphery; the other anti-system candidate does too. Overseas departments and territories voted massively for the far-left Mélenchon in the first round, then for Le Pen in the second (with high abstention in both cases).

As 2022 was a repeat of the 2017 runoff, the dichotomy between the center and the periphery seems to be taking hold in French politics. However, the third man of the election, Mélenchon, who followed on Le Pen’s heels with almost 22% of the vote in the first round, contends that there are actually three blocs emerging in French politics: a social-progressive bloc, he argues, is now competing against Macron’s centrist bloc and Le Pen and Zemmour’s nationalist bloc. The former is taking form: all leftist political forces (Greens, Socialists, and Communists) just joined forces with Mélenchon’s party La France Insoumise in a New Popular Ecological and Social Union (Nouvelle Union Populaire Ecologique et Sociale, or NUPES) ahead of the legislative elections, which will take place on June 12 and 19.

Five challenging years ahead for Macron

Emmanuel Macron has succeeded in being reelected for a second term — a feat that his two most-recent predecessors, François Hollande and Nicolas Sarkozy, failed to achieve. But nothing about his second term will be a political honeymoon, as he will face opposition from both the left and the far right.

Despite Macron’s clear victory, the mood in his camp on the day after the election was subdued. To beat Marine Le Pen and attract leftist voters after a polling scare, Macron worked on correcting his image on two fronts: his governing style, which is perceived as too vertical and solitary, and his policies regarding climate action, viewed as insufficiently ambitious. Now that promises have been made, in particular to make France “a great ecological nation,” the president will be closely monitored by his left flank to ensure he delivers.

In addition, Macron, who had to contend with the virulently anti-government yellow vest protest movement in his first term in office, will have to pay close attention to popular discontent. Four days before the second round, 59% of French feared that his reelection would divide the country. Abstention reached almost record numbers: 24% in the first round and 28% in the second, with almost 9% of voters casting invalid or blank ballots on April 24. Overall, then, over a third of French voters rejected the choice between Macron and Le Pen in 2022.

Macron can hope to regain some momentum, should he manage to retain his governing majority in the June legislative elections. His party, newly renamed Renaissance (Renewal), can count on a large coalition with other centrist and center-right parties, but will face frustrated nationalist opponents from Le Pen and Zemmour’s camps as well as revitalized leftist opponents from the newly created NUPES. Polls still indicate that Macron is likely to achieve his goal, avoiding an arduous cohabitation. The center remains valuable ground to hold in France, but challenges from the periphery are mounting.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Macron survives, but how long can the center hold in France?

May 6, 2022