A month ago, emboldened by the successful ousting of Tunisia’s Ben Ali, Egypt’s anti-government protesters took to the streets in Cairo demanding the resignation of Mubarak. And at that time, as my colleagues and I pointed out, many pundits wrote that the uprising in Tunisia was a special case, that the reality in Egypt and other countries was different, and that a “domino effect” would not sweep the region. Many analysts and national governments were proved wrong in the case of Egypt; and now, with few exceptions, neither governments nor policy wonks anticipated the turn of events in Libya, which until a few short weeks ago was widely seen as a stable country.

Six years ago, the consultancy Control Risks Group labeled Qaddafi as a “charismatic dictator” and stated that “politically, Libya is a stable country. There is currently no viable challenge to Qaddafi’s leadership. The security risk to business in Libya is very low…by far the greatest risk to foreign companies operating in Libya is its business environment.” At the same time, CNN, citing another global risk assessment report, wrote that “while the terrorist threat in Iraq has increased, Libya is among the safest places to do business…Qaddafi’s North African state…ranks with Scandinavia and much of Eastern Europe as being relatively safe from terrorism, organized crime and political violence.”

A year ago, BBC reported that “Libya [was seeing] ‘limited improvements in human rights.’” Four months ago Export Development for Canada stated that “external threats to Libyan regime stability are negligible and the Libyan security services have been generally effective at containing the threats posed by Islamic extremist groups.”

And only a month ago, The Economist Intelligence Unit wrote about the absence of immediate domestic threats to Qaddafi’s rule, stating that “he has been in power for over 40 years and will continue to be careful to balance the competing power structures within the political hierarchy…There is at present little immediate threat to the ruling elite. Political power will remain vested in the Libyan leader…”

Much will be said about the diplomatic “Faustian bargain” struck by Western powers with Libya; about how the West turned a blind eye to domestic repression and human rights abuses in order to secure access to oil and to co-opt Qaddafi away from terrorism. The events in Libya and throughout the region demonstrate that there is a need for an honest review of the increasingly discredited notion that “Diplomacy and Development” seamlessly go hand in hand in foreign assistance.

Yet, similar attention will need to be paid to revamping how political risk is assessed. It is not just until recently that political risk in Libya was considered low. While Western officials turned a “political blind eye” to Libya, most analysts simply turned the spotlight away from the country (and most of those still looking at Libya got it wrong).

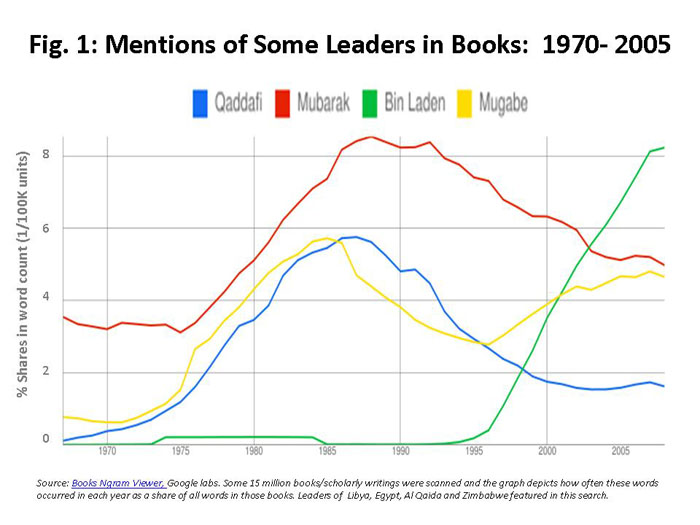

This problem is suggested in Figure 1, which shows the results of a Google Ngram search on the share of the selected words which appear in books and scholarly writings every year. Libya’s leader, Qaddafi was definitely in the analyst spotlight during the terror-related period of the mid-to-late ’80s, but since then interest in the leader waned. For instance, in recent times, Zimbabwe’s woeful head of state, Mugabe, has garnered over twice as much interest as Qaddafi. While Mugabe is another example of disastrous and callous leadership, it would be difficult to make the case that he is twice as powerful, dangerous or (human-rights) abusive as Qaddafi.

Clearly, in addition to governments and investors, many analysts also dropped the ball on Libya. In this context, it is also noteworthy how little attention was paid by officials, the media and pundits to Qaddafi’s mental health; at most there were mere mentions that he was “eccentric.”

Implicit in the traditional Faustian bargain between the West and despots like Qaddafi has been the belief that while human rights abuses are regrettable, they do not fundamentally affect or alter the West’s “geo-oil” diplomatic objectives, nor are they necessarily very detrimental to economic development.

In light of recent events in the Mideast, potently illustrated by Egypt and Libya, this notion ought to be challenged, since both political stability and development are being undermined precisely in countries with large democratic and human rights deficits. The countries’ citizens have understood this clearly for some time, and many see the West as being complicit. Of course, the West is not alone in sharing the blame; in May 2010, Libya was elected by 155 U.N. member governments to the U.N.’s Human Rights Council. Two months later Libya asked the U.N. to close its Human Rights Council office in Libya.

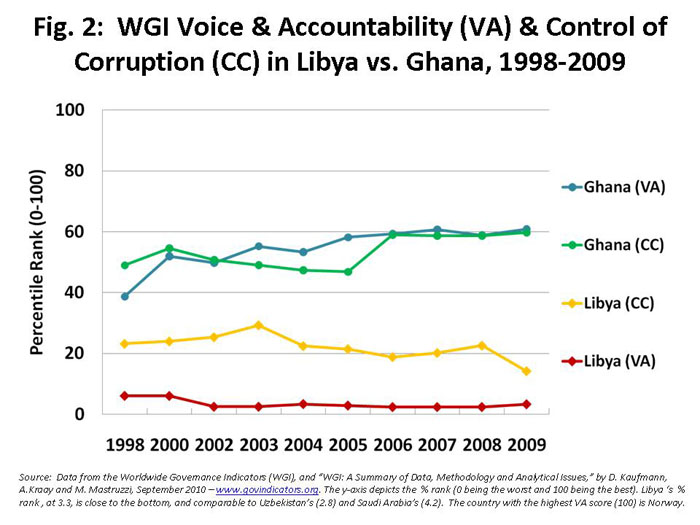

Consequently, even from a self-interested foreign policy perspective, the West will need to pay closer attention to democratic and human rights deficits in countries where they persist. It is telling to trace with data Libya’s democratic and human rights deficit and corruption control over the past dozen years, during the period it enjoyed “kid-glove treatment” from Western powers.

Libya’s abysmal performance on voice and democratic accountability is depicted in Figure 2, with the country rating among the bottom 10 countries in the world by 2009, after having experienced deterioration in its already poor performance. A similar deterioration occurred in the country’s control of corruption. Libya’s poor performance contrasts the experience of many other countries, like Ghana, whose performance has improved over the period and who nowadays ranks in the top half of the world on both dimensions.

The ICT-driven social network revolution, the importance of activist global TV networks like CNN and Al Jazeera, and the rise of bottom-up collective action have significantly increased the effectiveness and reduced the costs of “people’s insurrections” against illegitimate regimes which exhibit a major deficit in democratic governance and corruption control. Moving forward, political risk analysis and foreign aid agencies will need to pay closer attention to the importance of democratic governance factors, including civil liberties, human rights and corruption, in affecting political stability in a country—even where the repressive authoritarian machine is seen a priori as capable of brutal crackdowns against its people.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Libya’s Startling Failure: Unforeseen or Ignored?

February 25, 2011