We are in the midst of a global food crisis. The number of people affected by hunger more than doubled over the past three years, from 135 million in 2020 to 345 million in 2023. Global food prices remain well above pre-pandemic levels, with 38 out of 58 countries experiencing food crises reporting food inflation levels of over 10%, making basic foods unaffordable. The crisis is compounded by the crippling debt pressure facing low-income countries while funding to tackle hunger is meeting less than half of the total global needs. With global food supplies dwindling, and the Russian government’s recent decision to suspend participation in the Black Sea Grain Initiative, the situation is expected to get worse.

How can the global development community respond? We think one answer might lie outside the food and agriculture sectors—specifically, in the health sector, which has seen dramatic increases in financing, innovation, and coordination, especially in response to global health emergencies, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a new study, based on a literature review, expert interviews, focus groups, and quantitative analysis, we examined potential lessons from global health financing and institutional reforms that might translate to agricultural development and food security. We identified four key ways in which the food and agricultural sectors could learn from global health.

1. Invest in more grant financing

If used for medium-term agricultural development, grant financing could help bridge the gap between short-term emergency support and long-term interventions. A large-scale, dedicated mechanism for grant financing could have the potential to change the food security landscape altogether.

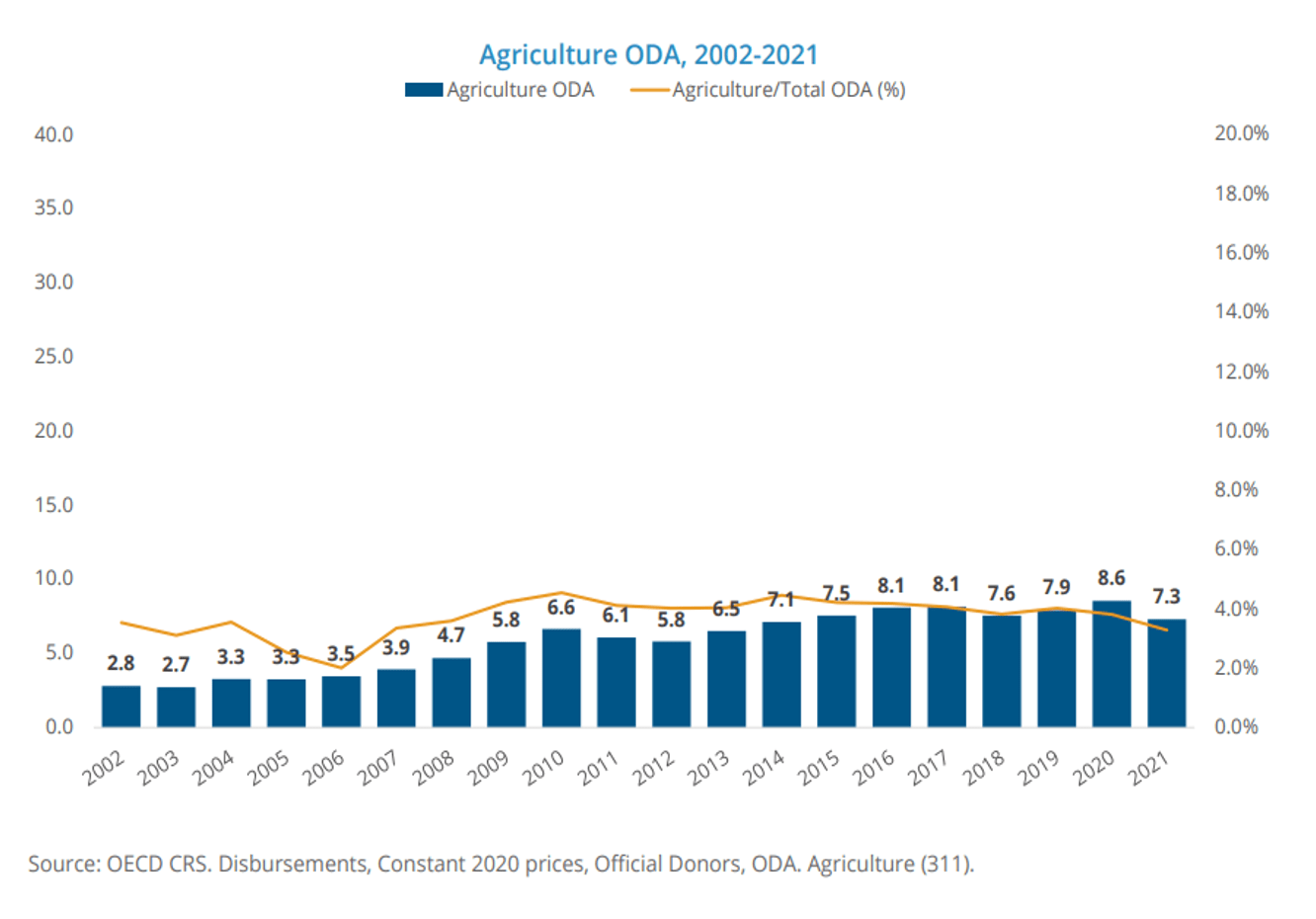

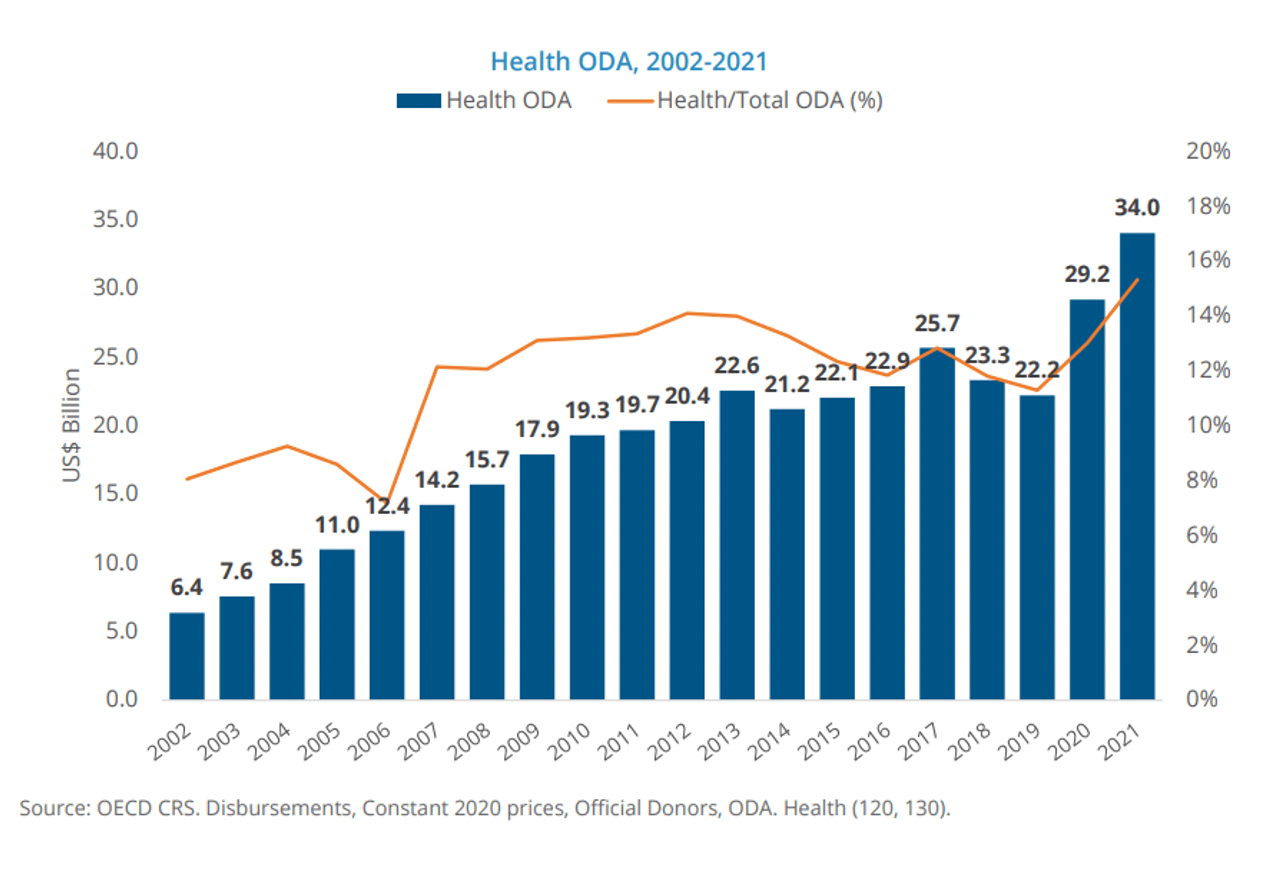

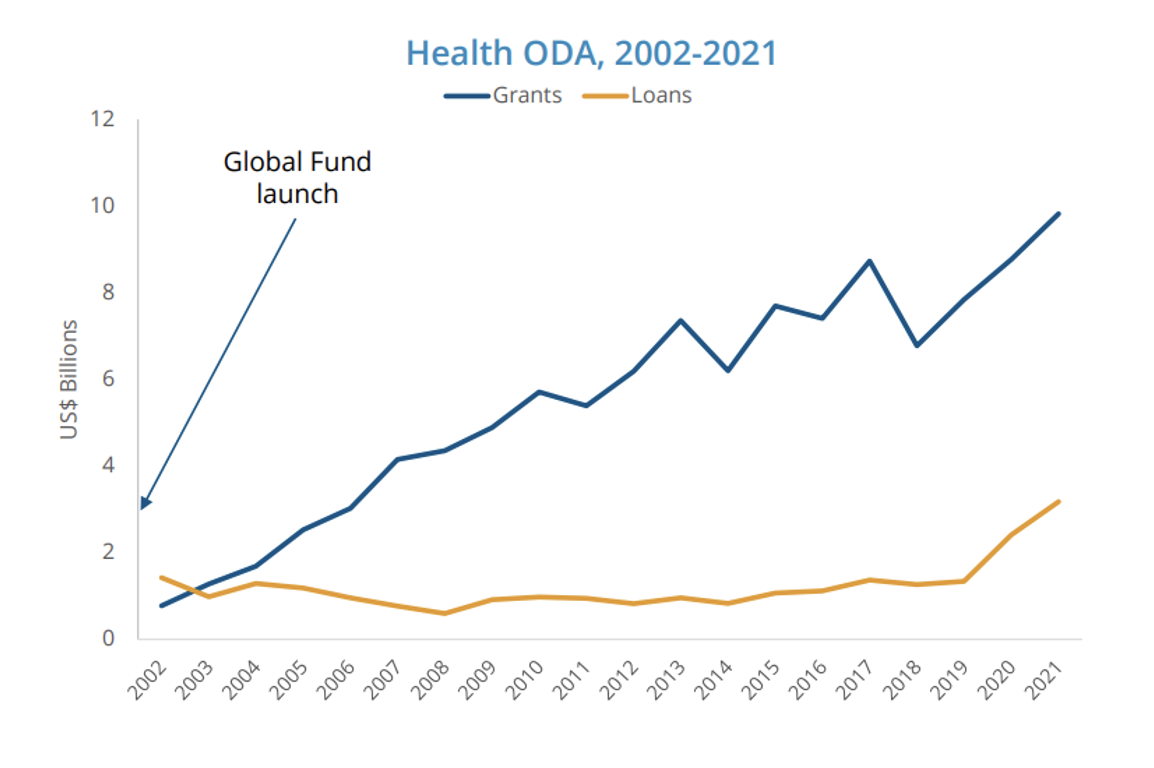

The global health sector has shown the way. While agriculture official development assistance (ODA) or aid rose from just $2.8 billion in 2002 to $7.3 billion in 2021 (Figure 1), health ODA increased by five times over the same period, from $6.4 billion to $34 billion (Figure 2). The health sector achieved this explosive growth in part due to the launch in the early 2000s of dedicated grant-based mechanisms like Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi), and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund). These mechanisms pooled resources from private and public donors, introduced new governance structures—engaging low- and middle-income country (LMIC) governments and civil society—and used new approaches to channel resources, such as results-based financing. Multilateral grant ODA following the launch of these two mechanisms has increased more than tenfold (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Agriculture ODA, 2002-2021

Figure 2. Health ODA, 2002-2021

Figure 3. Multilateral grant financing in health ODA 2002-21

There is a strong case for investing in more grant financing in food and agriculture. Research shows that agriculture is often seen as a “soft” sector that does not generate sufficient returns to cover debt-service repayments. Borrowing can thus correlate with “hard” agriculture projects (e.g., commercial or infrastructure-focused), which is not optimal for smallholder farmers, a group that produces one-third of the world’s food supply and is the key to achieving global food security. Grants, along with blended finance, can unlock commercial finance in the future. Given recent events, including the negative impact of COVID-19 on agriculture finance, coupled with high levels of LMIC debt, pro-poor lending may be the only way forward for now.

2. Invest more heavily in innovative financing mechanisms (IFMs)

The health sector has raised substantial resources from IFMs, such as vaccine bonds that frontload resources, airline levies that collect funds from travelers, debt swap agreements that cancel debt in exchange for country investments in health programming (e.g., debt2health); and advance market commitments for vaccine purchases.

Although there is significant potential for innovative financing in food and agriculture, existing examples of IFMs in food security (including development impact bonds, green bonds, and other instruments) tend to be small-scale. Studies indicate that innovative financing can support regenerative agriculture and climate adaptation, create more favorable market access conditions, and reduce the pressure on public financing. Most importantly, IFMs have the potential to catalyze private investment, including from financial institutions, private investors, impact investors, foundations, and philanthropists.

3. Foster inter-agency collaboration

The health sector pioneered new forms of such collaboration during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), a partnership to support the development, production, and access to tests, treatments, and vaccines, enabled light-touch coordination between funders and technical agencies, mobilizing $24 billion by October 2022. While donors still made pledges to the individual agencies, the fundraising was based on joint branding, investment cases, costing exercises, fundraising events, and a “fair-share” model to determine the fair level of contributions.

Following ACT-A, the COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Partnership (CoVDP) was formed in 2022 as a joint initiative by UNICEF, WHO, and Gavi to focus on 34 countries that still had less than 10% COVID-19 vaccination coverage at a time when vaccine supply was no longer a barrier. CoVDP leveraged funding from its core partners through an accelerated process, lined up technical assistance, and managed to increase vaccine coverage in 23 of the 34 countries in a short time (January to October 2022).

In the food security and agriculture landscape, the three U.N. Rome-Based Agencies—the Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, and the World Food Programme—play critical and complementary roles. However, limited governance and coordination are impeding their collective capacity to end hunger and malnutrition. Fragmented aid activities, lack of shared programming by funders, and disjointed humanitarian and development activities are inhibiting progress. Amid the current food crisis, the agriculture and food sectors could explore partnerships similar to ACT-A and CoVDP to strengthen inter-agency collaboration. A coordination model similar to CoVDP may even be useful to support food delivery in countries with the highest need during the current crisis.

4. Scale up investments in global public goods (GPGs)

Global health has seen significant investments in global functions, including:

- Investment in health data generation, collection, and metrics to assess progress and to make interventions more evidence-based and service delivery more efficient.

- Development of investment cases, such as the Global Fund investment case, which demonstrate and quantify the public health and economic benefits resulting from investments in the Fund.

- Investment in R&D to develop new medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics for poverty-related and neglected diseases. Annual funding for such R&D amounts to more than $4 billion annually, while major funding institutions have helped drive down prices for new tools to make them accessible to LMICs.

These investments were critical to increasing donor trust in the sector and for scaling up access to new health tools.

Recent studies in agriculture indicate the need to invest more in data, research, and the development and transfer of new technologies. The High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition and the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development recommend investing in data and evidence collection and in wide distribution (including South-South learning). The HLPE identifies the need to harmonize data collection standards globally. Multiple studies also suggest larger investments in research to identify policy-relevant food system solutions, including for small-scale producers.

Despite differences in thematic areas of work, the health and agriculture sectors face similar challenges, including resource mobilization and responding to global emergencies. As the nature of these challenges evolves, so should the global response. Cross-sectoral lessons offer one way to bring us closer to shaping policies and implementing solutions that can deliver results.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Lessons for the food and agriculture sectors: Drawing lessons from global health amid the current food crisis

October 30, 2023