These are odd times: Deep desperation and fear of downward mobility among the working and middle classes in many rich countries, with anti-system political manifestations such as Donald Trump’s domination of the Republican primaries in the U.S. and the vote for “Brexit” in the U.K. The narrative of both movements is characterized by racism, nativism, and a return to past “greatness.”

Meanwhile, in many countries in Latin America, a region long known for high levels of inequality and populist politics, the middle class is growing, extreme poverty has been all but eliminated, and the distribution of income has become more equal. And politics is borderline boring, although it remains unpredictable in a few countries. The most recent presidential elections in the region ushered in a center-right, fiscally conservative businessman in Argentina, and a Princeton and Oxford educated former finance minister and banker in Peru.

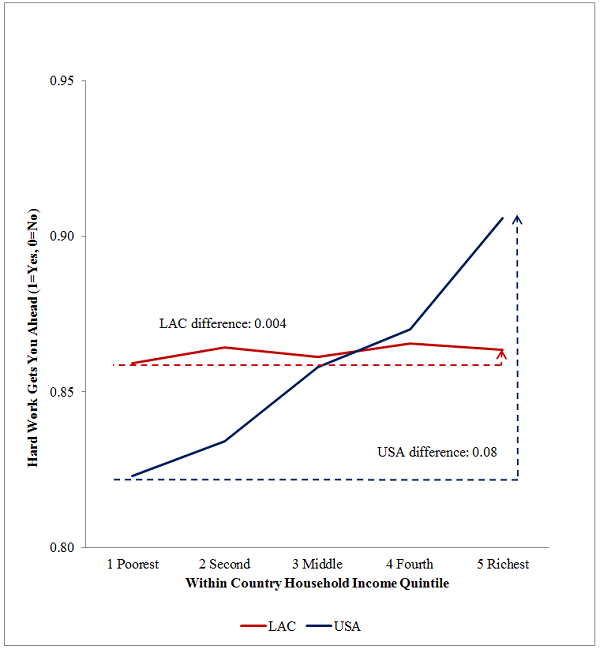

The comparison between markers of optimism and well-being in each context is particularly stark. The poor in Latin America are much more likely to believe that hard work will get them ahead than are the poor in the U.S., and the difference in the scores of the poor and the rich is significantly smaller in Latin America than it is in the U.S. (See Figure 1) The poor in Latin America are also much less likely to experience stress the previous day than are the poor in the U.S., another important indicator of well-being.

Figure 1: Gaps in “Hard Work Get You Ahead” scores between the poor and the rich: U.S. versus LAC

Source: Gallup World Poll

Equally remarkable, the poor cohorts in the U.S. who are most optimistic about their futures are those who were marginalized or discriminated against in the past. Poor blacks are three times more likely to score a point higher on an 11 point future optimism scale than are poor whites, while poor Hispanics are one and a half times more likely. Poor blacks are also half as likely (.52) to report stress the previous day than are poor whites. These same cohorts are more likely to support moderate political candidates, while support for Trump is highest among poor and middle income whites.

Life satisfaction and hope and markers of ill-being such as stress play an important role in determining objective outcomes. Individuals who are optimistic and believe in their futures are much more likely to invest in them. As a result they have better outcomes in the health, labor market, and income arenas. Yet making those investments also requires having the capacity to do so, and the high levels of stress typically experienced by the poor—related to circumstances beyond their control—lead to very short-term time horizons and even cognitive difficulties in planning ahead.

These differences in markers of optimism and stress also show up in objective health indicators. Mortality rates in the U.S. are being driven up by preventable deaths, due to suicide and opioid and drug addiction—clear signs of desperation—among middle-aged, uneducated whites. In contrast, mortality rates for both blacks and Hispanics have continued to fall, narrowing the gaps with whites. In Latin America, meanwhile, infant and child mortality have fallen markedly in recent decades, and life expectancy levels are as high as or higher than the U.S. level in the last 79 years.

What explains these differences? In the U.S. structural economic trends driven by globalization are shaped by geography, inequality, and the nature of the social safety net. The worst pockets of desperation associated with the hollowing out of the middle class are in previous manufacturing hubs in the middle of the country. These are typically small towns, which are left a wasteland if a key industry pulls out or relocates, as there is usually no alternative form of stable employment. Due to both climate and distance in these areas, residents are dispersed and have to drive to go anywhere, contributing to social isolation—another driver of ill-being.

In contrast, many cities tend to attract a range of firms and complementary institutions, such as universities and the arts, as Richard Florida describes in his work on “the creative class,” making them less vulnerable to the presence of one company. And residents are more likely to interact with each other on a regular basis, by walking the streets or taking public transport. In recent research, financial expert Tuugi Chuluun and I find that these same places tend to have higher levels of life satisfaction. They also have lower levels of mortality than do the isolated towns in the heartland, as economist Raj Chetty and colleagues recently found.

Inequality also plays a role. The U.S. has had the steepest increase in inequality of all countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development in recent decades, and the gaps between those at the top of the distribution and the rest are notable compared to those in the other countries, with the possible exception of the U.K. This gap between the very wealthy and the rest holds across traditional income based measures such as the Gini coefficient, CEO pay compared to other workers in firms, and indicators of access to top quality education from the preschool level to college. U.S. fiscal policy in recent decades has not done much to mitigate these trends and may have exacerbated them. The social welfare system in the U.S. also plays a role. Assistance is difficult to get and often comes in stigmatizing (and ineffective) forms, such as food stamps. Cash assistance for the poor, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, has been decreasing significantly over the past decade, and particularly so in Republican states.

In Latin America, in contrast, macro and fiscal reforms have generally benefited the poor and have been complemented by conditional cash transfer programs (CCTs). CCTs provide the poor with non-marginal amounts of cash assistance, conditional on households sending their children to school and taking them to regular health appointments. The basic presumption is that poor individuals are best positioned to choose how to spend their own income—and must be able to do so if they are to exit poverty— combined with a commitment to pulling them into society rather than stigmatizing them. As economist Nora Lustig and her co-authors document in their “Commitment to Equity” index, this combination of policies has results in major strides in reducing poverty across the region and decreases in inequality in at least five of the major Latin American economies.

But what is to be done about the tattered American dream? The underlying structural economic trends are as malleable as tectonic plates. Yet the markers of desperation are frightening enough that they are beginning to shift public attention from debilitating ideological divides to the deep social ills facing the U.S. today. That might provide some attention to the plight of those left behind. One part of the solution, meanwhile, is to reorient our social welfare system away from one that stigmatizes the poor and steers them farther behind psychologically. We should instead move toward more integrating programs, ranging from the provision of better vocational education to making college more accessible to low-income individuals to more broadly available preschool. Many of these are discussed in detail in the Brookings Social Mobility Memos. The key challenge will be bringing them into the spotlight of public debate.

Reducing inequality is difficult, making it even more unattractive for politicians to take on. Yet it is doable. And it is an area where Latin America can provide some important lessons. The region surely has its own challenges, but in this instance we could learn some lessons from our much more optimistic Southern neighbors.

Commentary

Lessons for restoring the American dream from Latin America

July 12, 2016