Below is a viewpoint from the Foresight Africa 2023 report, which explores top priorities for the region in the coming year. Read the full chapter on education.

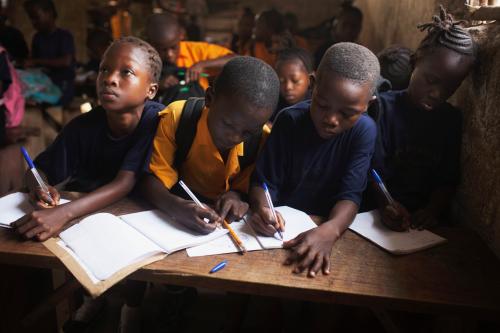

Conflict, insecurity, and the resulting humanitarian crises have imposed major disruptions on education systems in many parts of the African continent. Between 2020 and 2021, over 2,000 attacks on schools and educational infrastructures were documented in 14 African countries, with the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mali most affected. In the Central Sahel (namely Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger), the confluence of armed conflict and threats of attack have led to the closures of 7,000 schools, affecting the education of 1.3 million children and young people, while over 30,000 teachers are unable to teach. Girls are particularly affected and are less likely to return following these school closures.

Conflict, insecurity, and the resulting humanitarian crises have imposed major disruptions on education systems in many parts of the African continent. Between 2020 and 2021, over 2,000 attacks on schools and educational infrastructures were documented in 14 African countries, with the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mali most affected. In the Central Sahel (namely Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger), the confluence of armed conflict and threats of attack have led to the closures of 7,000 schools, affecting the education of 1.3 million children and young people, while over 30,000 teachers are unable to teach. Girls are particularly affected and are less likely to return following these school closures.

In 2022, the number of forcibly displaced people reached 36 million on the African continent—a threefold increase over the last ten years—and the majority are children and young people. If prevailing trends persist, the number of children and young people in need of education support in conflict-affected settings is likely to soar. Forced displacement acutely affects access to education and the continuation of learning, yet current education systems are not equipped to cope with the prolonged forced displacement facing conflict-affected settings. Forcibly displaced children, on average, benefit from fewer years of schooling, and are less likely to transition to secondary school.

Why does the provision of education matter in conflict-affected settings?

It is worth highlighting why education matters in conflict-affected settings. Education alone does not prevent conflict from erupting. However, education is central to sustainable peacebuilding and offers a tangible opportunity to break cycles of inequality that are a salient feature of fragile and conflict-affected states on the continent. In addition, education can address some of the drivers of violent extremism, although evidence shows that unmet expectations among educated youth could still fuel grievances and drive support for violent extremism. Third, keeping children in school during crises or conflict, provides a sense of normalcy, which is essential to their psychological well-being and cognitive development.

What should policymakers do to realize the promise of resolution UNSC 2601?

From a rights-based perspective and capability framework, the continuation of learning is central to how forcibly displaced communities reimagine their futures. In an effort initiated and coordinated by Niger and Norway, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) unanimously adopted the landmark resolution on the protection of education in armed conflict zones (UNSCR2601). Realizing the promise of this binding commitment (applicable to all U.N. member states) will require a more intentional response and coordinated approach—amidst crises that are increasingly protracted in nature, complex, and often with a regional dimension.

1. Reverse trends of declining government and humanitarian funding for education:

Insecurity imposes fiscal pressure on governments, which often lowers the proportion of government spending on education. This adversely impacts the ability of education systems to address the needs of children and youth affected by conflict, insecurity, and violence (see Figure 22 below).

Moreover, to be effective, interventions must draw on joint humanitarian and development praxes—yet in many African countries, notably in the Sahel, the humanitarian leg of education is direly underfunded: In Mali and Burkina Faso, respectively, less than 7 percent and 3 percent of humanitarian appeals for education have been met—compared to the global average of 50.7 percent.

2. Strengthen data and evidence on learning outcomes and trajectories of children and youth forcibly on the move:

There is a dearth of data particularly on internally displaced children, who often find themselves absorbed in the wider host communities. Consequently, their educational needs are often not fully accounted for, as they are not measured by conventional data. Quality data that is disaggregated, safely and ethically collected, as well as standardized can also support better diagnostics and the design of policies and programs. Beyond quantitative data, the use of qualitative measures that document the educational experiences and trajectories of girls and boys who are internally displaced can lay the foundations for more inclusive approaches, both for forcibly displaced children and their host communities.

3. Revisiting how education gets provided and for what purpose:

Much of education in emergencies focuses on primary education, with little attention afforded to post-primary and vocational training which young people in forced displacement cite as a valuable way to link education with economic opportunities. Moreover, the recognition that education is indeed already a priority for forcibly displaced communities can help reframe the angle of interventions, with a renewed focus on structural barriers. Lastly, quality matters, and even more so for populations facing crises: Without an environment that fosters learning and provides clear value, staying in school becomes nearly impossible for populations facing so many competing needs. Continuity of education in crisis settings, especially for girls, depends on quality and perception about the value of schooling.

In conclusion, it is imperative for African countries to invest in education in crisis settings, despite the associated challenges in fragile and conflict-affected countries. By doing so, Africa has an opportunity to reset the agenda for education in crisis settings and devise effective strategies to provide quality education for the growing population of children and youth who are affected by armed conflict.

Commentary

Learning on the move: Resetting the agenda for education and learning in conflict-affected settings

May 24, 2023