Chapter

03

EDUCATION AND SKILLS:

Equipping a labor force for the future

Essay 1

Essay 2

Strengthening education systems in Africa

Almost three years since the COVID-19 pandemic became a global threat and governments around the world shut down schools, the magnitude of the pandemic’s impact on children is still emerging. What is clear is that without swift action, the costs to Africa’s future could be staggering.

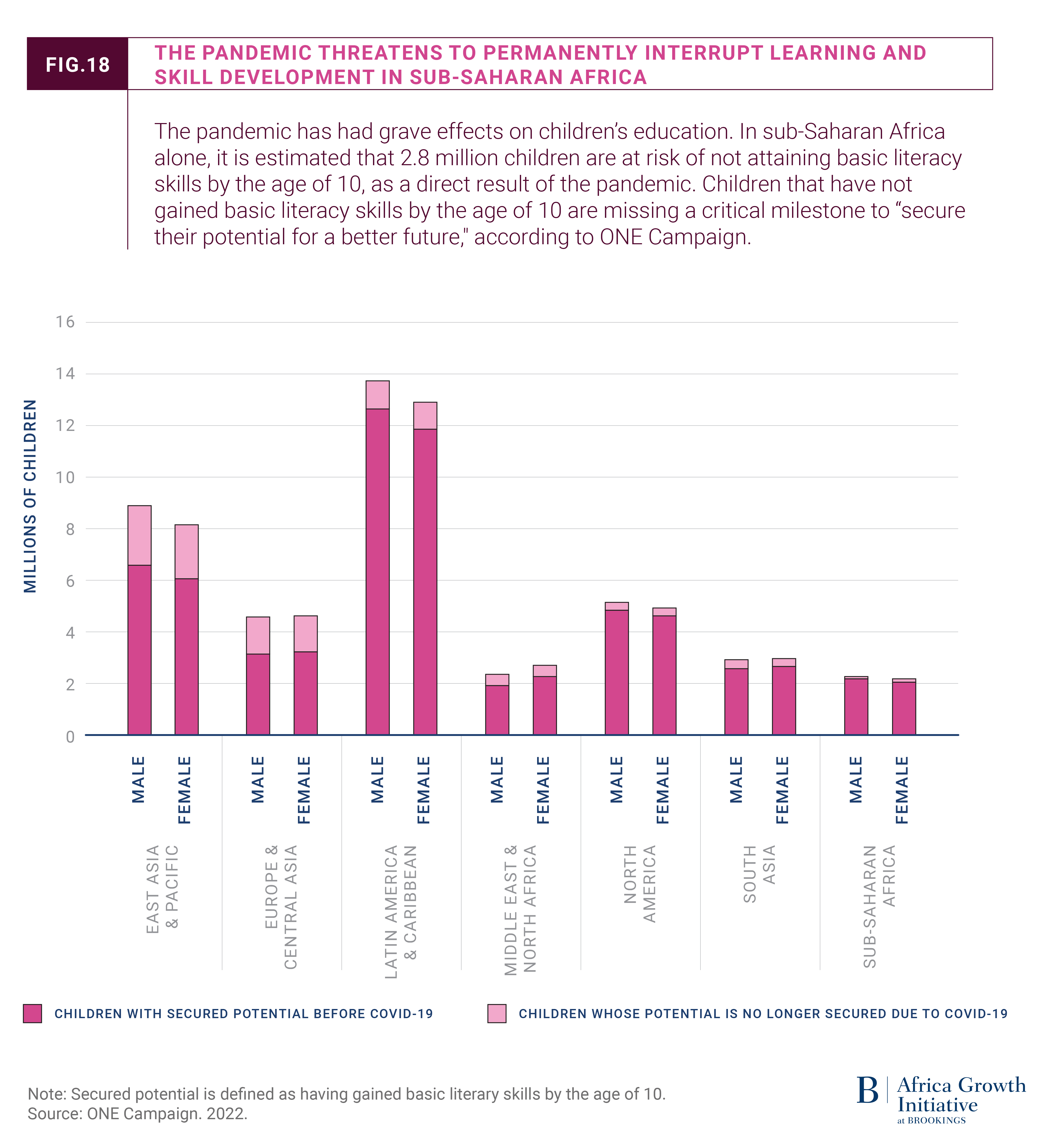

Even before COVID-19, nearly half the 10-year-olds in low- and middle-income countries could not read and comprehend a simple written story (see Figure 18). The pandemic has driven that to an alarming 70 percent.1

For the most vulnerable children and youth, the impacts were far worse, extending to their health, safety, and psychosocial well-being.

Child labor and early pregnancy rates have risen, and interrupted learning has put 10 million more girls at risk of early marriage, effectively ending their schooling altogether.2 More than 370 million children globally missed out on school meals during closures, losing what is often their only reliable daily source of nutrition.3 In some countries, this has translated to half of all children experiencing physical violence during school closures, and three quarters having to skip meals because of economic hardship related to the pandemic.

The pandemic exposed the fragility of education systems, including in Africa, but also their centrality to our vision of a flourishing future built on sustainable and inclusive growth. After all, children and young people represent our greatest hope–and our greatest resource–to build a fairer, more prosperous, and greener Africa.

“Schools in African countries were closed on average nearly eight months—in some countries much longer. Despite heroic and innovative efforts to keep children learning, there is mounting evidence that academic losses have been severe.”

This is why as we recover from the impacts of the pandemic, we must seize the moment to revolutionize the future of education in Africa, starting with transforming our education systems.

First, this means prioritizing education as a critical part of national and pan-African strategies to recover and rebuild. Governments must sharpen their focus on delivering 12 years of quality education for every child, regardless of their gender, household income, or whether they live in rural areas or with a disability. Sufficient and well-trained teachers are an essential enabler of this success, as is investing in at least one year of preschool for every child. We must redouble our efforts to eradicate violence, including gender-based and sexual violence, from our school and our communities so that every child is safe to learn. And we need a whole-of-society approach to combat gender inequalities that mean girls drop out of school to be married, or boys are forced out of classrooms to work.

During the U.N. Transforming Education Summit in September 2022, I was encouraged to see many African leaders pledging action to deliver on these priorities.

Second, education ministries and their partners need to identify and prioritize reforms that will deliver changes at scale; a transformation that reaches every school, teacher and child, starting with those who are being left furthest behind. The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) which I chair, is currently supporting over 40 African countries to do just this, starting by identifying and unblocking the political, technical, or financial obstacles that get in the way of children’s learning, and that keep the most marginalized out of school entirely. Some of the key obstacles to transforming education include limited domestic financing, owing to high debt costs, which mean countries are not spending enough on education, or are not spending efficiently and equitably. This is why GPE focuses on leveraging more and better domestic financing as the most significant and sustainable form of funding for education.

Third, we need to scale up investments to transform education systems, putting the most vulnerable children at the center. Investments in education can spur and work alongside other social investments, like health, nutrition, and psychosocial services to boost children’s health, safety, and well-being; as well as equip them with the skills they need to thrive in 21st century economies.

However, with food and energy prices stoking inflation globally, funds that should be rushing back to repair COVID’s damage to education systems, risk being redirected to other competing priorities.

We must not allow this to happen. I commend the 20 GPE partner countries, 16 of them in Africa, who have already signed on to the Heads of State Declaration on Education Finance, a powerful statement of intent to allocate at least 20 percent of national spending on education. I hope many more will join their ranks and translate these commitments into action for Africa’s children.

With rising debt costs and global inflation, it is also imperative that governments look for ways to expand their fiscal space and fund education investments in ways that do not drive up borrowing costs. At GPE we are looking at ways to collaborate with partner countries by supporting new agreements that divert debt payments to education budgets, or by supporting donors and creditors who will pay off debt costs, in return for results or additional spending in education (these can work alongside a swap where payments are diverted to education from a cancelled debt service; or a buydown where an entity which is not the creditor, nor the debtor, pays some of the debt costs in return for increased education spending). Innovative investment from international funders can also augment domestic budgets to bolster national efforts. This has been GPE’s approach for two decades, uniting broad coalitions from the development community and the private sector in support of country-led reforms.

“This year, as we mark 10 years since adopting Agenda 2063, let us put children and young people at the heart of our strategies for inclusive and sustainable growth, and commit to transforming education for a transformed future.”

Finally, we must build on the learning, innovations, and investments made during the past three years. The pandemic inspired new and innovative efforts by many teachers, parents, community leaders, and education officials in delivering lessons to children; any way they could. GPE was proud to support such efforts in 40 African countries.

In Eswatini, Rwanda, and Somalia, for example, television and radio stations offered daily lessons while some students in Zambia could tune into similar programming on solar-powered radios distributed to those without electricity. In Zimbabwe and Sudan, GPE supported the rapid expansion of UNICEF’s Learning Passport, an online and offline tech platform where children can access high-quality learning materials from anywhere, anytime.

In Burundi, specially printed materials were developed for remote learning while some children with disabilities in Gambia received regular phone check-ins as well. In Malawi, the government also focused on training teachers and staff to be prepared for school reopening, with adjusted curricula and improved, hygienic facilities with clean water and proper sanitation.

These examples provide a glimpse of African resilience and innovation in the face of crisis. But without a radical reinvigoration of our education systems, the Africa we aspire to is at stake. This year, as we mark 10 years since adopting Agenda 2063, let us put children and young people at the heart of our strategies for inclusive and sustainable growth, and commit to transforming education for a transformed future.

We must recognize that education itself is in extreme peril across Africa. Governments can, and must, put children first and ensure they can learn and learn well.

Educate to adapt, adapt to educate

Underlying the climate and adaptation crisis in Africa lies a human crisis. This includes a silent crisis in education which threatens the prosperity of individuals, communities, and nations. It is making people more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and prevents them from becoming a much needed and critical part of climate solutions.

Around the world, there is growing recognition of the relationship between climate change and education.4 Article 12 of the Paris Agreement recognizes the critical role of education in empowering all members of society to engage in and take climate action—both adaptive and mitigative. Climate action is also a thematic priority of UNESCO’s (2020) global framework on Education for Sustainable Development. In Africa, the Coalition for Education and Training on Climate Change acknowledges the role education plays in reducing the impact of climate change.

“If Africa continues at its current pace of educational investment, the continent will not be able to respond to the climate crisis.”

Despite its strategic importance to adaptation efforts, however, education has remained largely overlooked by the Parties to the UNFCCC. In mid-2022, only 40 of the 133 nations5 that had submitted an updated, revised, or new Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs) mentioned climate change education as an adaptation or mitigation strategy in their NDCs. Out of the 43 African countries that had submitted their updated, revised, or new NDC, 16 mentioned climate change education. In most East African countries, prioritizing education to empower the public with skills for climate adaptation is not consistently part of the sustainable development discourse.6

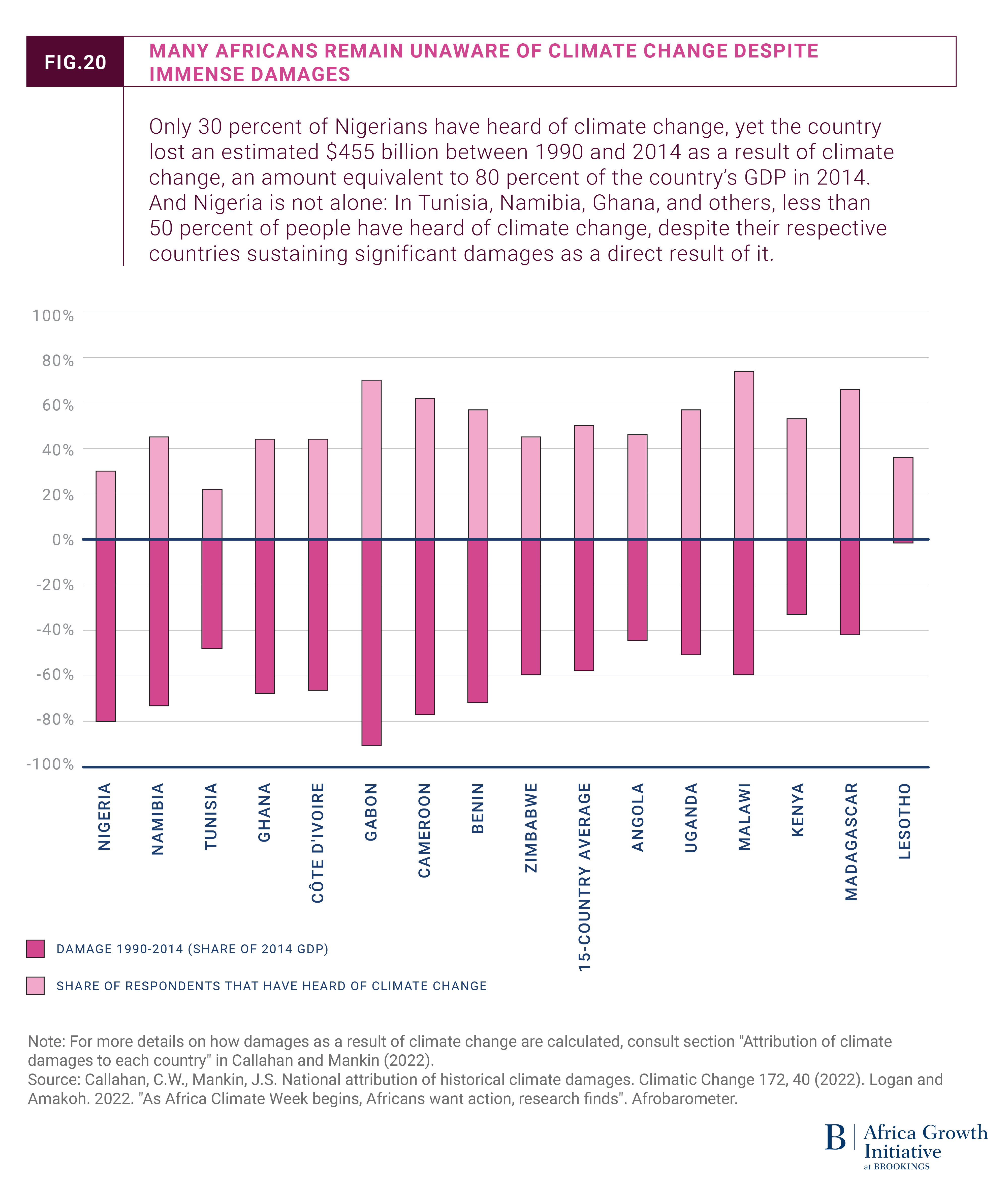

The impacts of climate change on education, and education on climate action, are insufficiently understood due to a lack of consistent and reliable data and research on interlinkages between climate and education (See Figure 20).7 This includes data on the direct impacts of extreme storms leading to destruction of infrastructure, of extreme heat leading to degradation of the learning environment and of droughts or famines stressing essential water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities critical for school attendance and retention. It also includes missing data on the indirect impacts through household coping responses in the face of loss of income and livelihoods or displacement, leading households to withdraw children (especially girls) from schooling. Climate change also impacts the health and well-being of educators and learners, reducing their readiness to teach and learn. These vulnerabilities are further compounded by systemic challenges in society such as gender and structural inequalities.

At the same time, education’s potential as a key instrument to help countries and communities adapt to climate change is hampered by the lack of understanding of the education crisis and its role as a key climate and adaptation strategy. Average years of schooling are the lowest in Africa compared to other regions. Progress in enrollment in secondary and tertiary education in Africa is slow, and enrollment in primary education has stagnated after experiencing a period of rapid progress around the turn of the new millennium.8 Yet a deeper and more structural problem lies in the quality of education in Africa. Of those that do go to school, millions leave school without basic literacy and numeracy skills. In sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa, only 11 percent and 23 percent of all 15–24-year-olds have basic secondary literacy and numeracy skills, respectively.9

Limited available data on the link between education and adaptation point to a strong relationship. UNICEF estimates that improving educational outcomes could reduce the climate risks borne by 275 million children globally. Recent analysis for the State and Trends in Adaptation 2022 Report also confirms that more education–specifically at the upper secondary and tertiary levels–is associated with higher adaptive capacity. With more education, individuals and households can better prepare for and respond to climate shocks through risk reduction, migration, the adoption of climate-resilient technologies, practices and/or behaviors, or by having more flexibility to learn new skills and/or to take on new jobs or find new livelihoods.10

Acting on the greater integration of education in adaptation is urgent. If Africa continues at its current pace of educational investment, the continent will not be able to respond to the climate crisis. Making education systems climate-adapted and ensuring investments in education can in turn drive adaptation, and will require action across four distinct areas:

- Monitor, diagnose, and plan for integrated education and adaptation strategies. More data is needed on a regular basis to better monitor, diagnose, and address local climate vulnerabilities on the education sector across the continent. In addition, greater efforts should be made to include education investments in adaptation policies and to give priority to the most climate-vulnerable communities or those least ready to adapt.

- Invest in climate adapted infrastructure. Schools could be designed not only as zero-emission buildings, but also capable of withstanding and/or adapting to climate-related shocks. African countries should avoid further investments in traditional “gray” education infrastructure that is vulnerable to damage or destruction, and places people at higher risk of exposure to climate-related hazards. African countries can also tap into locally available renewable energy and material resources to build green, climate-adapted infrastructure that is both feasible and cost-effective.

- Invest in a climate adapted education workforce. Strengthening the climate resilience and adaptive capacity of the education sector’s human resources— including teachers, trainers, facilitators, counsellors, staff, administrators, school leaders, and others—is critical to support the readiness of Africa’s education systems to adapt to (and respond to) climate impacts; and to unlock broader efforts across the continent to build a more climate-adapted, climate resilient workforce across economic and social sectors. This must include overcoming Africa’s teacher shortage, achieving better and more consistent compensation and training, and building cross-sectoral climate resilience teams. To enable the effective design of climate-adaptive education systems, a new form of workforce collaboration will be required that reaches across sectoral boundaries.11

- Invest in climate literacy and breadth of green skills. At a minimum, all learners must first acquire basic foundational and secondary skills, including literacy and numeracy, and climate literacy skills. But learners will also need to build specific technical skills that green jobs require—”portable skills” such as critical thinking and communication to facilitate climate adapted thinking, and transformative skills to enable work in complex realities and catalyze deeper systemic change.

To make progress on these four levers, a global effort is needed to establish an irresistible case for investment in education as a climate impacted sector—but also as a key solution to the problem. This global consensus should support countries to invest in education, and to build a movement for climate action and adaptation through education.

Endnotes

- 1. World Bank. 2022. “70% of 10-Year-Olds now in Learning Poverty, Unable to Read and Understand a Simple Text.” Press release for the State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 update. World Bank Group.] Even before COVID-19, a quarter of a billion children were already out of school. Now, because of pandemic-related disruptions, an additional 24 million students may drop out permanently, many of them in Africa.[UNESCO. 2020. “UN Secretary-General warns of education catastrophe, pointing to UNESCO estimate of 24 million learners at risk of dropping out.” Press Release. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- 2. UNICEF. 2021. “10 million additional girls at risk of child marriage due to COVID-19.” Press Release. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- 3. UNICEF. 2020. “Futures of 370 million children in jeopardy as school closures deprive them of school meals – UNICEF and WFP.” Press Release. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- 4. UN Climate Action. 2022. “Education is key to addressing climate change.”

- 5. Global Center on Adaptation. 2022. “Section 3 – Cross-Sectoral Themes.”

- 6. Abigael Apollo and Marcellus Forh Mbah. 2021. “Challenges and Opportunities for Climate Change Education (CCE) in East Africa: A Critical Review.”

- 7. ACE. 2022. “Lack of Education Causes Climate Denial.”

- 8. David K. Evans and Amina Mendez Acosta. 2020. “Education in Africa: What Are We Learning?”

- 9. The Education Commission 2015. “Number Of Youth Without Secondary Education Level Skills.”

- 10. Walker et al. 2022. “Education and adaptive capacity: the influence of formal education on climate change adaptation of pastoral women.”

- 11. The Education Commission & Dubai Cares. 2022. “Rewiring Education for People and Planet report calls for cross-sectoral collaboration.”

Viewpoints

STEM education in Africa: Risk and opportunity

Ruth Kagia looks at ways to improve STEM education for Africa’s youth.

International education financing will make or break the SDGs

David Sengeh and Mathias Esmann underscore the importance of international education financing to advance sustainable development in Sierra Leone and beyond.

Learning on the move: Resetting the agenda for education and learning in conflict-affected settings

Halimatou Hima discusses methods for better educating youths displaced by conflict.

To prosper, Africa’s children and youth must learn

Safaa El-Kogali discusses how to improve learning outcomes for youth in Africa.

Foundational skills for a more inclusive Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) in Africa

Louise Fox and Landry Signé argue for a focus on foundational learning to prepare African youth for the jobs of tomorrow.

Next Chapter

04 | Health Assuring health security for all