Economic relations between Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and Asia are at a crossroads. LAC countries face the dual challenge of reigniting trade with Asia, which remains the world’s fastest-growing region, while also diversifying and adding value to their exports to said region.

Latin America also faces a radically different global trade environment than a few years ago. In late 2016, several LAC and Asian countries were on the verge of entering the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). A year later, the U.S. has abandoned the TPP and relinquished its traditional role as a driver of global economic integration in bilateral and multilateral negotiations.

While the turn in U.S. trade policy creates uncertainty, especially for closely integrated LAC economies such as Mexico and Central America, it also gives renewed impetus to several projects to improve economic relations between Asia and LAC. At the same time, regional efforts to bolster trade within LAC are accelerating, spurred by the efforts of initiatives such as the pacific Alliance and key countries like Argentina and Brazil. The European Union has had increasing relevance as well, with lengthy trade negotiations with the South American trade bloc Mercosur and major steps to modernize the EU-Mexico Free Trade Agreement both nearing conclusion.

As shown in Figure 1, it took less than 20 years for Asia to become Latin America’s second largest partner. The region now has an opportunity to deepen trade and investment links with Asia even further, addressing key trade barriers and promoting a more diversified and sustainable relationship. As new options emerge, challenges will also arise surrounding the need to prioritize among competing negotiations, avoiding uneven participation by LAC countries, and ensuring LAC-Asia talks do not slow down regional integration within LAC.

Below is an analysis of ongoing Asia-LAC trade integration projects. The discussion could hardly be timelier: Every major Asia-LAC trade deal has held key talks over the past few months, underscoring the evolving nature of the Asia-Pacific trade architecture.

The best options for better integrating LAC and Asia

The region’s approach to integration with Asia should address a few key issues. First, market access concerns such as high tariffs, tariff escalation, and burdensome regulatory standards continue to impede LAC’s ability to add value to natural resource-based exports. Lowering these barriers must be a priority. Next, a subset of LAC countries—Chile, Peru, and, to a lesser extent, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Colombia—account for nearly all formal agreements with Asia. Moving forward, the region should be wary of further divergence between this group of deeply integrated countries and others such as Argentina and Brazil with no current free trade agreements (FTAs) with Asia. Finally, greater emphasis is needed on LAC’s own regional integration efforts—particularly as the Pacific Alliance and Mercosur continue to make progress in their convergence agenda.

Which options are on the table? In order of increasing scope (and decreasing progress to date), the four main Asia-LAC integration processes are: (i) the TPP-11 (without the U.S); (ii) the Pacific Alliance plus Asian partners; iii) the expansion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to LAC; and iv) a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP).

Revival of the Trans-Pacific Partnership

After U.S. withdrawal in January 2017, the 11 remaining TPP partners forged ahead with negotiations toward a new iteration of the deal, with Japan playing a leading role. During a January 2018 summit in Tokyo, these countries ironed out the final terms for a new pact, which they plan to formally sign this March in Chile.

The agreement, now called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), strips out several provisions on intellectual property and investor-state dispute settlement, but maintains most of the original TPP, which will reduce barriers on an important number of goods of LAC-Asia trade. Importantly, the CPTPP will allow for accession of new members, opening the door for other LAC economies to join.

Addition of Asia-Pacific countries to the Pacific Alliance

The Pacific Alliance—made up of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru—has been a key player in integrating LAC with Asia. In June 2017, the alliance announced the inclusion of three Asia-Pacific countries (Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore) as associate members alongside Canada. This associate status represents a new category that entails negotiations of a free trade agreement with the Pacific Alliance as a trade bloc. South Korea has also shown interest in becoming an associate member. In addition, the Pacific Alliance includes other Asian partners as observers, and it has a working agenda with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

The first round of negotiations with associate members, held in late October, focused on setting a timetable for future rounds, technical talks between thematic working groups, and establishing deadlines for the presentation of proposals on market access, rules of origin, trade in services, and other issues. A second round is taking place in Australia at the time of writing, and a third is scheduled for early March in Chile.

The Pacific Alliance has pursued deep integration by harmonizing rules of origin and other trade rules between countries. Although additional deals between the alliance and Asian partners would therefore represent an important step toward liberalizing trade between LAC and Asia, the feasibility of including Asia’s major economies as associate members is still unclear. In addition, the successful conclusion of CPTTP negotiations has created some uncertainty regarding the path forward for these negotiations, since all parties but Colombia are part of the agreement.

Expansion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership to LAC

The RCEP is a trade deal between 16 Asia-Pacific countries whose negotiations have been underway since 2013. In November 2016, Chile, Mexico, and Peru expressed interest in the deal, raising the possibility of the deal becoming a vehicle for Asia-Latin America integration.

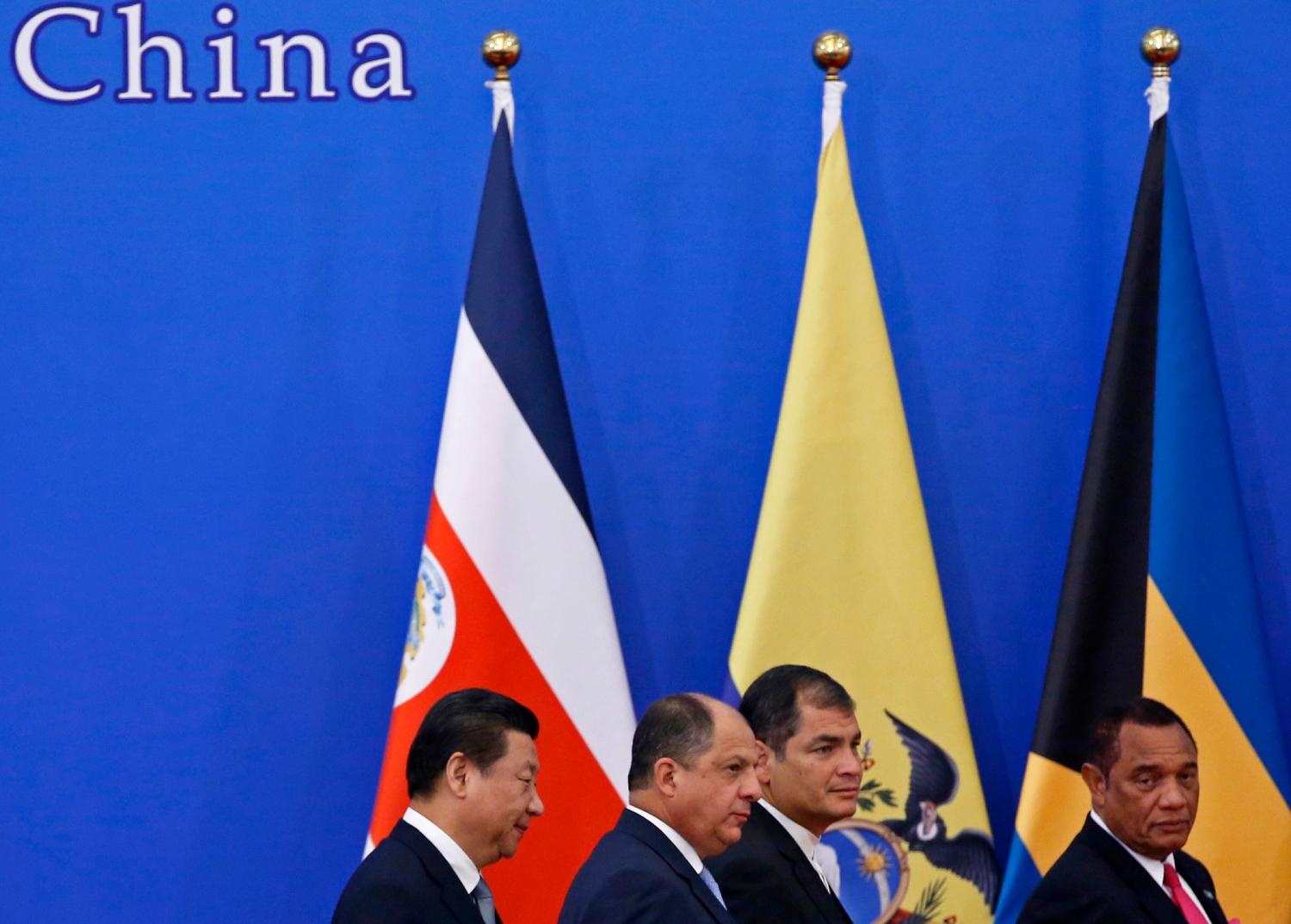

The RCEP includes major economic Asian powerhouses like China, Japan, and India. China has been a main driver of the RCEP process, with Chinese President Xi Jinping urging a “speedy conclusion of RCEP negotiations” during the APEC Summit last November.

The parties have yet to agree on key market access issues, and the final deal may fail to meaningfully reduce barriers in areas such as agriculture, textiles, and food products where greater market access is a priority for LAC.

A Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific

The idea for a free trade area spanning the Asia-Pacific region has been an explicit goal of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation bloc since its 2014 Leader’s Summit, which endorsed the Beijing Roadmap toward a FTAAP. President Xi gave the project a rhetorical boost at the 2016 APEC Summit, calling it “critical for the long-term prosperity of the Asia-Pacific.”

At this stage, however, formal negotiations toward a FTAAP have not begun, and the APEC Summit last November produced only a generic commitment to “the eventual realization of an FTAAP to further APEC’s regional economic integration agenda.”

Regional integration as a basis for global engagement

This increasingly important Asia-Pacific agenda will benefit from closer regional integration between LAC countries. Most importantly, in recent years the Pacific Alliance and Mercosur have tried to bring LAC’s two largest trade groups closer together. In early 2017, trade ministers established a roadmap for cooperation on trade facilitation, customs agencies, trade promotion, support for small and medium-sized enterprises, and regional value chains, among other issues. Pacific Alliance and Mercosur countries are pushing for bilateral deals, including ongoing Argentina-Mexico and Brazil-Mexico negotiations. Beyond traditional trade agreements, the region is making inroads in facilitating trade through agreements between customs agencies and other entities involved in the international movement of goods. Moreover, a more integrated region is a more attractive region for foreign direct investment as well as a more services-oriented region.

With Latin America itself more closely integrated, improved ties between any LAC and Asian countries will have spillover effects to the rest of the region. Asian manufacturers in LAC will be more likely to source inputs from neighboring countries when regional tariff barriers are low, rules of origin are less restrictive, and customs procedures are streamlined. To realize this goal, however, LAC countries involved in multiple, at times overlapping, trade negotiations should make sure these are mutually compatible, especially in areas such as rules of origin, in order to avoid ending up with a complex network of different trade rules for different partners. In addition, trade negotiators in countries with multiple projects underway will have to consider how to strategically sequence different agreements. Delivering on this agenda would help spark a new wave of Asia-LAC trade and investment.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Inter-American Development Bank, its board of directors, or the countries they represent.