It goes without saying that the current ideological divide precludes progress on much of anything in President Obama’s new budget.

However, it’s interesting to see how a few items—a child-care assistance bill, a manufacturing bill, a worker-training proposal—have surfaced as potential tests of a new bipartisan effort in the Senate to break through the current gridlock on a few limited fronts.

Especially intriguing is the case of the National Network of Manufacturing Institutes (NNMI), which we have discussed here and here. First proposed in March 2012 and formally requested in Obama’s 2013 State of the Union Address, the NNMI initiative calls for the investment of $1 billion in a set of 15 manufacturing innovation hubs (en route to a projected 45), but it has not fared well in a divided Congress and now returns in the new budget outline. However, there seems to be some progress currently. With manufacturing and innovation popular topics, the hubs initiative—in the form of S.B. 1468, with three GOP co-sponsors—has now emerged as the number two item on the Senate’s tentative docket of actual floor markups. Don’t hold your breath, but this is an encouraging development.

Yet even if gridlock does ultimately rule out congressional action, there is still an interesting story here: The NNMI initiative remains a promising example of how to kludge out progress in other ways.

Most notably, the hub initiative’s focus on “bottom-up” collaborations between firms, universities, labs, and government to advance manufacturing innovation based on regional assets turns out to be pretty good policy and politics.

After all, the very concept of the hub network reflects a new form of federalism wherein the federal government convenes and provides seed money, but leaves project design and delivery to the creativity—and matching resources—of “bottom up” partnerships.

This approach wisely pairs national direction-setting with local variation and proximity to firms and local industry clusters (all good for innovation). But it also makes limited money go farther.

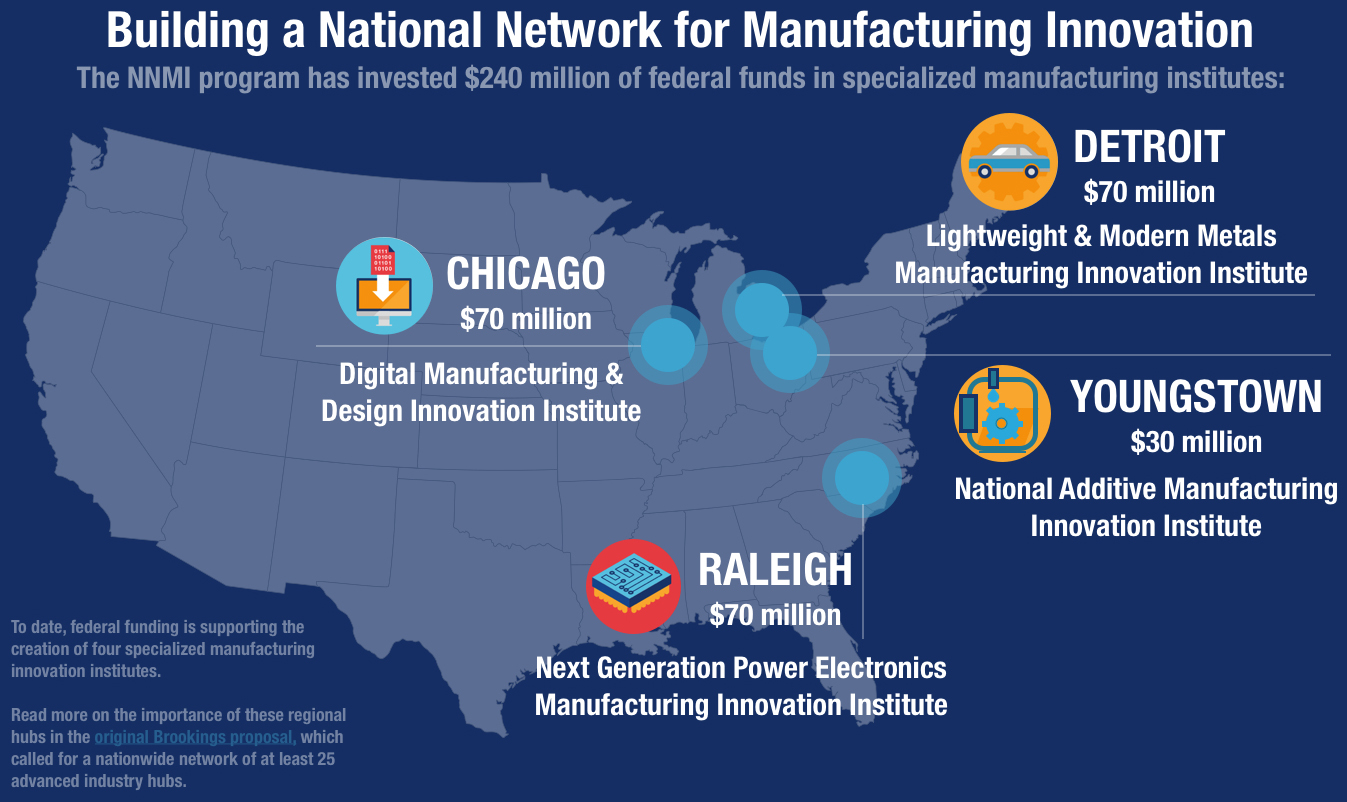

For example, the first manufacturing hub (on “3-D printing”)—awarded last year to a consortia of partners in Youngstown, Ohio—won $30 million in federal funding by assembling over $40 million in private-sector contributions; partnering with 79 companies, universities, community colleges, and nongovernmental organizations; and proposing multiple timely research and development projects. Similarly, the partnership that won the competition to launch Chicago’s just-announced “digital manufacturing” hub has attracted over $3.50 in private funds for every $1 of federal money.

There are political benefits as well. With the administration using existing money to establish initial manufacturing institutes, the map is now studded with four established hubs and a competition for another one underway. In each case, local and national business leaders, universities, governors, mayors, and even members of Congress are enthusiastically buying into the need to ignite innovation in America’s advanced manufacturing industries. One result: There are now three GOP sponsors of NNMI legislation in the Senate and 15 co-sponsors (give or take) in the House. It is also worth noting that five governors—including four Republicans—have provided state financial support to the new institutes. By working from the “bottom up,” the initiative is steadily enlisting support, demonstrating results, and generating demand for a little more top-down action.

In a word, the steady progress of the manufacturing institute concept likely reflects the concept’s smart leveraging of the non-federal nation’s emerging creativity and vitality: its industries, its states, and its regions.

In that regard, the progress of the NNMI initiative—while slower than what is needed—confirms that advances can be made despite gridlock in Washington.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Kludging Out Progress: The Case of Manufacturing Hubs

March 6, 2014