On Tuesday, September 17, Israeli voters will head to the polls once again. These will be the second national elections in less than six months.

Following elections in April, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appeared to have won. The right-wing bloc in the new 21st Knesset received 65 seats of the total 120, assuring him — so we all assumed — a fourth consecutive term in office.

However, five of those 65 seats belonged to the party of Avigdor Liberman, Netanyahu’s former foreign minister and defense minister (and previously his close aide in the 1990s). Liberman surprised everyone by playing hardball on what appeared to be a minor issue. Liberman picked up the mantle of the secular right wing, popular among an important segment of the right, including many immigrants from the former Soviet Union (Liberman himself was born in Moldova). He insisted on the passage, verbatim, of an existing bill that would have, ostensibly, institutionalized the military service of Ultra-Orthodox Jewish men, just as other Jewish Israeli men serve.

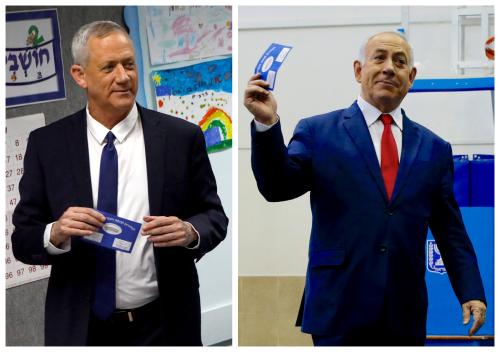

This was, to be clear, political theater. The bill in question would have changed very little about universal conscription. But Liberman seized on opportunity. Refusing to budge, he raised the possibility that Netanyahu would fail to form a coalition in the allotted time — having received the most recommendations to be prime minister, Israel’s president tasked Netanyahu with forming a coalition. Failing to form the coalition would have essentially disqualified Netanyahu from the role, and the president would have passed the task to another Member of Knesset (MK), such as opposition leader Benny Gantz of the Blue and White list, another MK from Netanyahu’s Likud party, or any other MK the president thought had a chance to succeed. (See a primer for the April elections here for an explanation of Israel’s electoral system.)

To stave off such a possibility, Netanyahu tried to cajole and entice almost every member of the opposition to defect and replace Liberman, to no avail. At the last moment, to prevent another MK from getting the chance to form a government, Netanyahu’s Likud party initiated a bill to dissolve the Knesset and call new elections. On the night of May 29, the 21st Knesset became the shortest-serving in Israel’s history, with the odd scene of Netanyahu voting to undo his recent, supposed victory.

The stakes

As odd as these new elections are, the stakes are actually high. For Netanyahu himself, at stake is not just his tenure but possibly his personal freedom. He faces the possibility of criminal charges in three cases, including for bribery. In February, the attorney general — appointed by Netanyahu himself — announced his decision to indict the prime minister, pending a final hearing with the prime minister and his lawyers, scheduled for October.

As odd as these new elections are, the stakes are actually high.

Should Netanyahu be indicted, he could technically still serve as prime minister — assuming his coalition partners agree to serve under him in such circumstances. When the charges were published, I wrote that the “end is nigh for Netanyahu” on the assumption that MKs would have a limited willingness to stomach such a scene and to serve under a prime minister on trial. I may well have overestimated their capacity for shame and — foolishly — underestimated Netanyahu’s political ability even in these most extreme of circumstances. And yet, Netanyahu might also lose this time, and his legal woes are a central factor in that possibility.

For Israel, too, the stakes are very high, even if one would be forgiven for thinking this is all about one man. First, should Netanyahu win outright, he will almost certainly seek immunity from prosecution. He can do so under current law with approval of the Knesset, which can grant immunity to MKs for acts committed in the due course of Knesset membership. The problem for Netanyahu is that Israel’s Supreme Court would likely intervene and reverse such a Knesset decision. The Supreme Court is the guardian of the largely unwritten constitution of Israel and the frequent focus of ire from the right for its supposed overreach in defense of process, minority rights, and human rights.

A Netanyahu victory, then, might mean changes to a Basic Law (essentially an article of the unwritten Israeli constitution) which would strip the Supreme Court of such powers. With no written bill of rights and no clearly defined limits to majoritarian power, such a move would leave little check on majoritarian whims. Reform, certainly, might be in order, but one done for the clear purpose of one man’s interests, with repercussions that could last generations, would be a danger to a pillar of Israeli democracy.

Second, in a clear election stunt, Netanyahu endorsed applying Israeli law (a form of annexation, really) to the Jordan River Valley. This move, which used to be a far-right agenda item, would likely be a prelude to further annexations in other parts of the West Bank. This too would be a momentous decision, with dramatic ramifications for the state. The green light from Washington has moved even the cautious Netanyahu to eschew his gradual approach in favor of overt and, to my mind, reckless moves, whether they actually happen any time soon or not.

Who will win?

Beats me.

Netanyahu failed to form a coalition following the April elections because his bloc had exactly 60 seats of 120 (sans Liberman). He needed 61. Had the right-wing New Right party (now part of the “Yamina” amalgam list, which means “rightward”) passed the minimum threshold of 3.25% of the vote, he would now be well into his fifth official term as prime minister. In a redux election, those 60 seats could easily be 61, or they could be 59. Anyone who claims to be sure of either outcome is lying.

An average of the last permissible public polls (it is illegal to release polls in the three days before an election) suggests a very tight race. The right-wing bloc averages 59 seats, just two shy of a Netanyahu win. A Netanyahu victory would therefore not be a surprise. The small two-seat difference also depends on two unknown factors.

First, there is no precedent for a second national election within six months. We do not know what this will mean for voter turnout in different parts of the population. Some segments are more reliable voters than others — Ultra-Orthodox tend to fulfill their civic duty much more than others do — but which will be affected by the political environment is anyone’s guess.

Second, very small parties may or may not pass the electoral threshold of 3.25%. Labor-Gesher and the Democratic Union lists, on the left, are not far from the threshold, although they are currently expected to squeak through. On the far (far) right, Otzma Yehudit, a successor to the outlawed and racist Kach party, is now polling at the minimum four seats. If it passed, it may edge the right-wing bloc past 60. If it fails, it may bring the bloc and Netanyahu down.

If Netanyahu gets to 61 seats, he will form a coalition and may perhaps be able to entice some from the center — even Gantz or Liberman — to join his government. If he does not reach that number, the focus turns to a new kingmaker, Liberman. He has stated clearly that he would demand a secular national unity government—including the Likud, Gantz’s Blue and White, and his own Yisrael Beitenu, but without the Ultra-Orthodox—giving Gantz’s Blue and White party a de-facto veto. Blue and White have made clear they would not sit in a government led by Netanyahu should he be indicted. (A final decision on his indictment is expected in December.) But Gantz would also find it extremely hard to form a coalition himself, with a badly splintered center-left and opposition from many on the right to his partners in Blue and White. Israel may then find itself at an impasse.

In previous impasses — the hung Knesset of 1984 in particular — the president has intervened to broker broad governments, supporting the push for national unity. One clear way out would be a government headed by a Likud member other than Netanyahu. Names include Gideon Sa’ar, a former minister, Foreign Minister Yisrael Katz, or even the Speaker of the Knesset Yuli Edelstein. The Likud could surprise everyone with another name if things came to that.

With a new Likud leader, Gantz and Liberman could then join, claiming victory in removing Netanyahu (the raison d’etre of Blue and White) but serving in a right-wing led government. To get there, the Likud would have to part ways with its leader, something its rank-and-file members are as loath to do as its leadership is keen to. It may take another full failed attempt by Netanyahu to form a coalition before they break rank, and even that may not be enough. There is one thing they and others on the right wing seem to agree on: They do not want a third election merely to save one man.

When the coalition haggling is over, way past the Jewish High Holidays and the indictment hearings, Israel may have exactly the same prime minister as it has had since 2009. Or it may have someone most people abroad have never heard of. Or, just maybe, all will be decided in a national election or two in the year 2020.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israeli elections redux: What you need to know

September 13, 2019