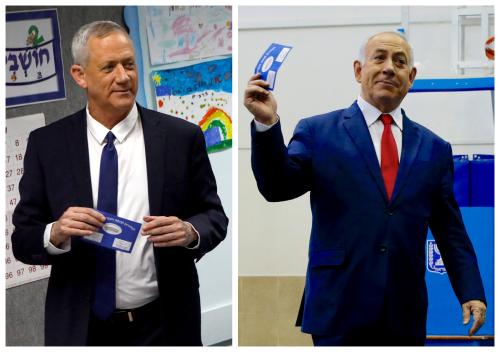

On April 9, Israeli voters handed Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu a clear electoral victory. Netanyahu, whose win reflects the structural advantage enjoyed by Israel’s right wing, will now turn his attention to his legal troubles, including a likely indictment, writes Natan Sachs. This piece originally appeared in The Atlantic.

If Israel holds elections in the year 2029, you might do well to bet on the right wing Likud Party. Benjamin Netanyahu will probably no longer be prime minister by then—he faces an uphill battle to be prime minister a year from now if, as is likely, criminal charges are brought against him. On Wednesday morning, however, Bibi celebrated his fourth consecutive electoral victory and his fifth overall. He pulled through despite the pending criminal charges, despite a fairly unified opposition, and despite the many politicians fatigued by his tenure. The public as a whole does not appear to share that fatigue.

Israel has a multi-party system, and its elections can be inconclusive. But voters appear to have handed a clear victory to the right wing parties that support Netanyahu, at least for now. Netanyahu will now move to form a coalition similar to his previous one, formed between his own enlarged Likud and other right-wing factions.

This summer, Netanyahu will become Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, surpassing the founding leader of the country, David Ben Gurion. At about the same time, his lawyers are scheduled to meet with Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit to try and change the latter’s mind about indicting the prime minister for bribery and other charges in three criminal cases. Even while Netanyahu celebrates his victory among Israel’s 6 million eligible voters, his attention is squarely set on Mandelblit. Israel’s other politicians, meanwhile, are catching their breath from an ugly, whirlwind campaign, and coming to terms with the fact that they may need to campaign again before long, if Netanyahu is forced by his coalition partners to resign.

Netanyahu’s next major challenge will be trying to arrange for legislation to grant him immunity from prosecution, holding off the attorney general’s decision until after Netanyahu leaves office. It will be a tall order. Some in his future coalition have an incentive to see him go, with a chance to succeed him. Many of them would privately view such legislation as unethical. At least two potential coalition parties and even some Likud members have said publicly that they would not support it. Still, those statements were made before the elections, and the morning after an election tends to grant politicians absolution from campaign promises. It’ll be tough for Netanyahu to pull off immunity, but it’s not out of the question.

Two parties now stand far ahead of the others: the Likud and the opposition Blue and White, led by former military chief of staff Benny Gantz, Netanyahu’s main challenger. The presence of two large parties harkens back to the early 1990s, when Labor and Likud dominated the political scene. Then, however, the minimum threshold for a party to enter the Knesset was only 1 percent of the total votes. Since then, the minimum has been gradually raised to 3.25 percent, placing a slew of parties in danger of not entering the Knesset, and placing their votes in danger of being discarded altogether.

Indeed, the results available as of Wednesday morning are preliminary: They include 97 percent of regular stations reporting, but do not include absentee ballots cast by military personnel—a considerable number of voters. They show two parties very near the minimum threshold of 3.25 percent, that could find themselves in or out of the Knesset when the final count is in later this week—the New Right party of outgoing Minister of Education Naftali Bennett and Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked and one of the two alliances of Arab-voter based parties—the very nationalist Balad and the Islamist Raam. Depending on whether one or both of them get into the Knesset, the seat allocation of other parties might change, although the right-wing advantage seems secure.

*Preliminary results, before votes of military personnel and other absentee ballots are counted. Raam-Balad and New Right are very close to the minimum threshold

For Bennett and Shaked in particular, this will be a stinging defeat, even if their New Right does make it in. The two stars of the young guard on the right saw themselves as potential prime ministers. They chose to abandon the Jewish Home party, their Modern Orthodox-based party of old, and founded the New Right. Their hope was to move toward the center of secular society and offer a general right-wing alternative to the Likud rather than the sectarian Jewish Home, thereby creating a platform for national leadership. Even if they do make it in the Knesset after all votes are counted—still quite possible—their gambit will have failed.

The alliance they left behind, between the Jewish Home party and its partner Tkuma, feared falling below the minimum threshold. Netanyahu himself intervened—to his shame—to cajole them to join forces with Otzma Yehudit, a party of former members of Kach, the party of Meir Kahane, barred from elections in Israel after one term for his racism and shunned by all political parties since the 1980s. Likud Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir used to walk out of the Knesset when Kahane spoke, to signal his disgust. The president at the time, Haim Herzog, would not even meet Kahane when he was elected to the Knesset.

Netanyahu succeeded in saving a Right Wing faction from obliteration—the United Right List based around the Jewish Home made it in—but to Israel’s credit, none of the Kahanists will have made it in to the Knesset in the end. One was barred from running by the courts, another was too far down the list. (He may enter later, if ministers from the alliance resign from the Knesset).

The Labor Party was one of the night’s biggest losers. The dominant ruling party of Israel from before the state’s birth until 1977, it has generally been the main opposition party since. It has declined precipitously since the outbreak of the Second Intifada. It should not be counted out—it has a base, and talented parliamentarians, but its failure in these elections is nothing short of astounding.

The key to the Israeli election system, however, lies not in the identity of the largest party, or the specifics of the smaller ones, but in the balance among competing blocs of parties. After elections results are certified, the Israeli president will call the newly elected members of each party to congratulate them and ask who among the members of the new Knesset they recommend as the next prime minister. The multi-party nature of the Israeli system produces difficult-to-manage coalitions, but the picture in the 21st Knesset appears clear. The preliminary results suggest that the Netanyahu will receive the recommendations of around 65 of the 120 new MKs, and he will be tasked by President Reuven Rivlin to form a new coalition. He will need all or nearly all of the right-wing parties to govern, and the price will be steep—in portfolios and in policy.

The results of the election can be attributed to the errors of the Blue and White’s campaign and the political inexperience of its leader, Benny Gantz, or to the political genius of Netanyahu. In truth, however, the right wing entered these elections—as it might enter those in 2029—with a clear advantage. The basic structure of Israeli politics has been skewed in its favor for decades.

Of the 14 elections Israel has held since 1977, the Likud has won 10, lost three, and come to a tie in one more. Since the early 2000s, moreover, the doctrinal approach of the left has been discredited in the eyes of many Israelis. The national trauma of the suicide bombings of the Second Intifada, and the perceived failure of the unilateral disengagement from Gaza, convinced most Israelis that attempts at grand engineering of reality are naïve, even reckless; that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has no neat solutions; and that trying and failing to achieve them is worse than not trying at all. I’ve called this elsewhere an anti-solutionist approach to Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians: conflict management, rather than conflict resolution, serving also as cover for a consistent slide toward incorporating much of the West Bank into Israel.

As a result, Israelis have consistently shunned the left over the past decades. As Tamar Hermann and Or Anabi of the Israeli Democracy Institute recently found, a full 63 percent of Jewish Israelis (about 80 percent of the population) self-define as being on the right or center-right of the Israeli political map. Only 14 percent of Jewish Israelis, (plus nearly all of the Arab Israelis) define themselves as being on the left or center-left. Eighteen percent self-define as pure center. These election results reflect that, with Labor’s demise and the poor showing of the left-wing Meretz party as well.

The center or the left can win an election on a very good day, but for a long time, Israeli elections have been the right wing’s to lose.

On the face of it, not much will change in Israeli policy. The best indicator of what Netanyahu might do in the future is what he has done in the past. But if Netanyahu thinks he might succeed in passing legislation granting himself immunity, he will surely try, making him dependent—for his personal freedom, not just his political fortunes—on his coalition partners, including the most extreme on the right.

His incentive to move toward formal annexation of settlement blocs will grow, even though this would be a dramatic move that goes against his own cautious, gradual nature. Netanyahu does not want annexation of the whole West Bank, and the vast majority of his coalition partners and of Israelis do not, either. But Netanyahu and many Israelis do not believe this is a dichotomous choice. They believe they might move, gradually, to annex settlements, while still leaving much of the Palestinian population to the Palestinian Authority. The groundwork has been laid—much of it by Naftali Bennett, ironically—and the long-term ramifications could be severe, foreclosing of possibility for meaningful separation from the Palestinians, and raising the danger of a permanent one-state reality.

In normal times, such rash moves would be met by strident opposition from Washington, but these are not normal times in Washington. Without a brake from abroad, a new coalition may be the victim of both its own worst impulses and the hour of extreme vulnerability of its seemingly mighty leader, five-time Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israel’s right-wing majority

April 11, 2019