That the first decade of the 2000s was Africa’s most economically successful period since the beginning of official statistics has been amply voiced. Between 2000 and 2010, sub-Saharan Africa (developing only) grew at over 5 percent per year, large enough to produce real gains even in the face of sustained population growth (of about 2.7 percent per year). According to the latest estimates, poverty also decreased, from 58 percent at the turn of the century to 43 percent in 2012, and substantial progress was made on non-monetary dimensions of living standards. Africa’s performance in the first 10 years since the turn of the millennium gave birth to the “Africa rising” narrative, with the continent destined to keep on growing and developing fast in the decades to come, providing the next (and last?) frontier for high-return private investment, corporate profits, and global growth. “Africa has a real chance to follow in the footsteps of Asia,” The Economist wrote in 2011, and several more decades of sustained growth will all but eradicate the worst forms of poverty and the multitudes of deprivations many Africans face each and every day.

The reasons behind Africa’s reversal of fortunes have been hotly debated. Party-poopers tend to believe that Africa’s rise was simply a matter of favorable terms of trade, and that the structural changes needed to project Africa on a sustained higher growth path—mainly related to industrialization—are woefully absent. Granted, say optimists, commodity prices were sky-high during Africa’s rise, but even countries with limited exportable resources grew fast. What mattered at least as much as commodity prices were economic reforms and improved political governance. Macroeconomic policies greatly improved since the late 1990s, political regimes on the whole somewhat liberalized, and competitive elections—though still wanting in many places—gave a voice to previously marginalized groups. Also important, 2000-2010 was a relatively peaceful decade in Africa, with many internal conflicts and civil wars that had wreaked havoc on countries’ economies in the 1980s and 1990s dying down (such as in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo) and few fresh ones being started.

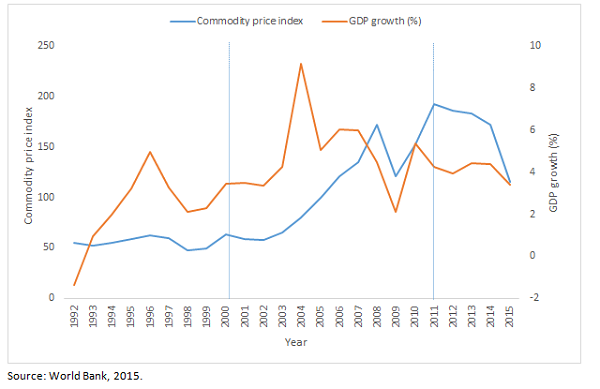

How is the “Africa rising” narrative holding up five years into the new decade? The answer, in the best tradition of economics, is two-fold: on the one hand, not too bad; on the other hand, not too good. Not too bad, as growth in sub-Saharan Africa remained solid until 2014. Not too good, as many of the perceived drivers of Africa’s performance, emphasized on both sides of the spectrum, have taken a turn for the worse. Commodity prices started declining after 2011, and tumbled in 2015, and with that economic growth (see Figure 1). In 2015, economic growth slowed to an estimated 3.4 percent, its lowest rate in 15 years except for the financial crisis and hardly higher than the rate of population growth.

Figure

1

: Tumbling commodity prices since 2011, followed by a growth slowdown

Also, after a relatively peaceful decade, events in Cote d’Ivoire, the Central African Republic, Mali, Burundi, Nigeria, South Sudan and other places reminded us that violence, fragility, and civil wars are hardly distant memories, and both the number and intensity of violent conflicts have been picking up in recent years (see Figure 2—the spike in battle-related deaths in 1999/2000 is due to the Eritrea-Ethiopia border conflict). The quality of country economic management, as measured by the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment, has slid back to where it was following an improvement between 2005 and 2010. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance, a composite indicator measuring the quality of governance in every African country, also suggests that progress in governance quality has been stalling since 2011.

Figure

2

: Following a peaceful decade, conflict-incidence and battle-related deaths are on the rise

So where does that leave us? The drivers of Africa’s performance in the previous decade appear to have weakened or reversed, though of course the time series is too short to draw any firm conclusions. What we do know, however, is that growth is slowing, commodity prices are down, violent conflicts seem to be back with a vengeance, and improvements in political and economic governance are slowing, if not reversing. What does this mean for Africa’s fate over the five to 10 years to come? Will Africa continue to rise, or will the ghosts of the past come back to haunt us once again? Only time will tell.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Is Africa still rising? Taking stock halfway through the decade

January 19, 2016