Less than a decade ago, economic ties between India and China were strengthening. China became India’s largest trading partner, and when Xi Jinping visited India in 2014, Chinese officials were talking about the large investments in India to come. Today, however, Indian scrutiny and restrictions on a range of Chinese activities have increased, and geopolitical differences have exacerbated economic friction. To discuss this shift and the state of India-China economic ties, Ashok Malik, partner at The Asia Group and former Indian official, joins host Tanvi Madan.

- Listen to Global India on Apple, Spotify, and wherever you listen to podcasts.

- Watch on YouTube.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

Transcript

-

03:20 The economic relationship between India and China, looking back

-

10:13 India’s current mood about economic ties with China

-

12:58 What is India’s de-risking approach toward China?

-

18:15 How does India’s private sector see the de-risking approach?

-

22:31 Are Indian tech startups concerned about restrictions on China?

-

23:48 Has China pushed back on India’s scrutiny and restrictions?

-

27:00 What is the reason for de-risking rather than decoupling?

-

29:45 Implications of India’s de-risking approach for companies in other countries

-

32:03 Are New Delhi’s restrictions on China affecting multinational companies seeking to do business in India?

-

35:14 Lightning Round: What is the biggest myth you hear about India-China economic ties

[music]

MADAN: Welcome to Global India, I’m Tanvi Madan, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, where I specialize in Indian foreign policy. In this new Brookings podcast, I’ll be turning the spotlight on India’s partnerships, its rivalries, and its role on the global stage. This season our conversations will be focused on India’s relationship with China, and why and how China-India ties are shaping New Delhi’s view of the world.

In 2011, Narendra Modi, then chief minister of the Indian state of Gujarat, gave a speech in Beijing. Speaking of China-India ties, he noted, and I quote, “Over the years, our relations have further strengthened. We are committed to making them still better, fruitful, and productive. I have seen growing interest among Chinese companies to work in Gujarat. We wholeheartedly welcome them. My personal visit is to reinforce that process.”

The development of economic ties with China wasn’t the story of just one Indian state. In 2001, India’s trade with China stood at a paltry $3 billion. But as bilateral political ties and comfort levels grew, so did trade and business. By the time Modi delivered those remarks in China, it had become India’s largest trading partner, with goods trade at over $70 billion.

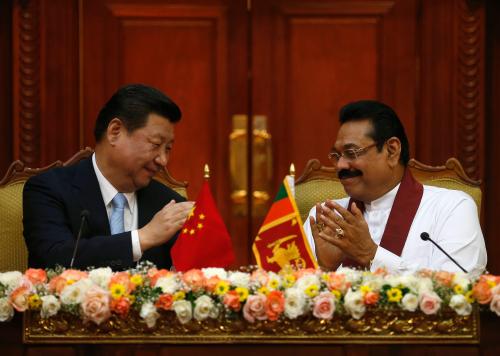

When a few years later, Modi became prime minister in 2014, China welcomed his coming to office, since it thought this was someone who literally wanted to do business with China.

Ahead of Xi Jinping’s first visit to India that year, Chinese officials on their part were talking of potential Chinese investments of over $100 billion flowing into India in the next few years. Given that Chinese investment into India had been relatively limited at that point, this was welcome news in New Delhi. There was hope that China would address India’s concerns about the trade imbalance, and there was also hope that economic interdependence would alleviate political strains and even perhaps facilitate solutions to geopolitical problems between the two countries.

Fast forward a few years, however, and the story is very different. Bilateral trade between China and India remains high, even as China’s share of India’s imports has reduced somewhat. But the Modi government has imposed several measures restricting or imposing extra scrutiny on Chinese activities in the economic, technology, telecommunications, civil society, and even media domains. Instead of economic ties facilitating political bonhomie, political friction has exacerbated economic concerns.

[music]

To discuss this shift and the state of India-China economic ties, today my guest is Ashok Malik, partner at the Asia Group and chair of its New Delhi-based India Practice. Between 2019 and 2022, he served as a policy advisor and additional secretary in India’s Ministry of External Affairs. In addition to other roles in government, he’s also worked at think tanks and in the media. And he’s also the author of the 2012 book, India: Spirit of Enterprise, which explored the expansion of the Indian private sector.

Welcome to the podcast, Ashok.

MALIK: Thanks, Tanvi. Glad to be here.

03:20 The economic relationship between India and China, looking back

MADAN: Ashok, we’ve spent the last few episodes of this podcast talking about the geopolitical dimensions of the relationship. Today with you, we’re going to focus on economic ties between China and India. If we’d been around a decade ago, we’d have had a very different sense of that relationship. I recall that now Foreign Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar, who was then Indian ambassador to China, in about 2012 said that India-China economic ties were the game changer in the relationship. If we had been talking about 15-20 years ago, or even when Prime Minister Modi first took office in 2014, how would you have described the economic relationship between India and China?

MALIK: There was certainly an optimism in the early part of the century, in the first decade of the century, when both India and China were growing. Growing in very different directions, China was growing as a manufacturing power, India was still a services economy with some hopes of manufacturing, but not quite there. But there was hope that trade and economic complementarities would weld the two countries together.

If you go back to the beginning of the century, in the year 2000, just after Prime Minister Vajpayee comes into office, China’s GDP at that point is double India’s GDP. In 2014, when Mr. Modi came to office, China’s GDP was four-and-a-half times India’s GDP. Essentially something happened in those 15 years under Mr. Vajpayee and then under Dr. Manmohan Singh, when China’s GDP just took off. And India’s GDP grew, but China’s grew much faster and became much larger.

Today, China’s GDP is about five times India’s GDP. So, in a sense, Mr. Modi’s decade has seen India keep pace with China and in many years grow faster than China, including this year. So, in terms of size, China still is only four-and-a-half or five times India’s GDP. And I use the term only very advisedly because that is a significant number. So, the gap has not grown, but it hasn’t come down either. And in absolute terms, that gap is widening because sheer numbers mean China is bigger.

When Mr. Modi came to office in 2014, these problems, this imbalance was already becoming obvious and worrying for Indian policymakers and economic strategists. In particular, the growing dependence on China for manufactured goods as a result of the Indian manufacturing economy hollowing out, as a result of China’s entry into WTO opening markets for it in India, even without it quite planning or realizing those markets.

India’s FTAs with ASEAN, with Singapore before that, with Thailand, all of these opened up avenues for China. Again, without China quite planning a foray into the Indian market the way it had to the West 10 or 15 years earlier. So, when Mr. Modi came to office, or even before that, it was apparent that when it came to electronics, mobile phones, computers, or even cheap toys for our children and frying pans for our kitchens. Chinese manufacture was energizing the Indian consumption boom, but it was also creating an imbalance and it was creating a potential security risk, especially as more and more Indians used smartphones and computers.

Yet, it was felt that China would be cognizant of the size and potential of the Indian market and not want to lose it, and therefore would be willing to create some space for India, create some space for Indian imports or exports from India into China, especially in pharmaceuticals, IT services, certain types of food and dairy products where India is competitive vis-à-vis Chinese demands, consumer demands.

So, when Mr. Modi came to office, he sought to ease business visas for the Chinese. He sought to give them more of a stake in the Indian economy, and felt that they would reciprocate, and the trade balance would converge—or if not converge, at least be less imbalanced.

Quite honestly, that bet hasn’t delivered. Because Indian pharmaceutical products are well regarded across the world. Indian IT services are well regarded across the world. Somehow, they just don’t seem to pass muster in China. So, our pharmaceutical products keep failing the Chinese equivalent of the FDA and its test. Our IT services are barely seen in China. And there are clearly all sorts of non-tariff barriers and hurdles that are created. That hasn’t really changed.

In addition, there is suspicion about the way the Chinese use technology. Something as simple as preloaded apps on Chinese mobile phones are now viewed very suspiciously, and this led to a lot of apps being banned in India.

Finally, post-2020, post the clashes in Ladakh where the Chinese sought to change the border, and post the experience during the pandemic when, frankly, there were supply chain constraints, some of China’s making, some not of its making because of the lockdown. And in some cases, especially during our second wave, Delta wave, there was price gouging by Chinese companies, including state-backed Chinese companies for products or equipment like oxygen concentrators.

That has led to a stiffer approach to China, and the idealism and hope that Dr. Jaishankar spoke about in 2012, or, frankly, Mr. Modi also entertained in 2014, no longer exist.

MADAN: I think it’s also kind of reflective of a journey that many countries have had, particularly in the West. And so, in that, it actually reflects—whether in Europe, whether in US, whether in India—kind of similar journey, perhaps at different times perhaps some countries still not having gone through that whole journey. But nonetheless, that journey of seeing China and economic ties with China as an opportunity. And now increasingly seeing it as a vulnerability.

Last year, Dr. Jaishankar, now India’s minister of external affairs, said that globalization and technology are not really economic issues, they’re strategic issues. And so, his description of them was very much part of that whole rather than perhaps a decade ago we would have seen economic ties on a separate track facilitating political ties perhaps, but largely continuing on its own.

And I think on India-China, you did see trade particularly grow, investment not as much, but nonetheless, you really saw even Prime Minister Modi, as you said, talk about learning from China, from particularly the manufacturing and infrastructure side, and to see them perhaps invest in those sectors.

10:13 India’s current mood on economic ties with China

Today Ashok, you mentioned we’ve gone from optimism to, if not pessimism, realism or pragmatism around the world about economic ties with China. How would you describe India’s current mood on economic ties with China?

MALIK: Well, in two areas: resilient and reliable supply chains, and transparent and trusted technology, both hardware and software. In these two areas, economic price and cost imperatives are not the only things that count anymore. Quite frankly, they have become part of a larger national security architecture, not just in India, but in many countries. And this is where there is a certain wariness of investing too much in the China basket.

Second, as India’s own manufacturing ambitions have finally started to grow. You know, from Echelon 1 we moved to Echelon 3, we still have 30 echelons to climb. I’m not suggesting we’re really close to matching China—far from it. But there is a determined movement towards manufacturing at least some of what we need and use in India at home and becoming part of global manufacturing value chains, especially in electronics. This of course, started off with mobile phones, including Samsung and Apple, but it’s growing to other areas. This is where a sense of diversification from China, of de-risking from China, is certainly starting to articulate itself.

Second, in terms of Chinese infrastructure investment, in 2012 and 2013, Chinese infrastructure companies were the toast of the world. Their achievements had us all awestruck, all of us across the world. And people actually asked, should we have the Chinese coming building ports or roads in India? In fact, there was a Chinese company that built a pipeline in India, a gas pipeline.

So, today, those questions are not being asked, because starting 2014 with CPEC [China-Pakistan Economic Corridor] and 2017 with BRI [Belt and Road Initiative], we’ve seen how Chinese infrastructure projects have panned out in many countries, including countries in Asia, and in South Asia. They have created dependencies. There are projects with no commercial logic or economic rationale in some cases. There are projects that seem to have a strategic imperative rather than a business one. And they have in some cases made very fragile polities even more fragile. Again, this has not helped popularize the Chinese model, if I could put it mildly.

12:58 What is India’s de-risking approach toward China?

MADAN: Ashok, we’ve seen as part of this effort of de-risking a series of measures from the Indian government over the last few years, some even preceding the Galwan clash, the border clash in summer 2020, going to when the pandemic was raging. We’ve seen these restrictions on several Chinese investments and activities. So, whether it’s foreign direct investment facing extra scrutiny, or it’s the famous app bans, including that of TikTok, as well as some constraints in other arenas, telecom and Huawei—essentially though not by name—not being allowed into 5G trials, for example, in India, which had been a possibility, or at least on the table a few years ago.

Tell us a little bit more about this de-risking approach and how you see it. But also, you mentioned the geopolitical dimensions: were there specific aspects of heightening or heightened political concerns that led to these moves being made to essentially say this is now a risk for India and therefore India needed to protect itself from it. What does it say about India’s view of the future of the China-India relationship?

MALIK: You know, you spoke about Galwan and the same year, the pandemic and the pandemic experience. I think what Galwan and the pandemic experience did was sharpen already existing or emerging trend lines. They didn’t create new trend lines. They just sharpened trend lines that were already visible before the pandemic and before the Galwan clash.

In terms of key and critical infrastructure, whether telecom infrastructure or power infrastructure especially, or in terms of Chinese digital products—both tangible products and intangible products, including preloaded apps on Chinese mobile phones and what they were doing in terms of data mining—that whole basket of telecom, telecom infrastructure, telecom equipment, and power equipment is now seen with some suspicion. And you do not want a potential Chinese bug in your system. It’s fine if I’m buying a Chinese multi-plug charger to use when I travel to the U.S. next, but it’s not fine if my power utility is using Chinese equipment. That trust is not there. So, if it can de-risk and look elsewhere, it will. And that is happening. That’s again happening in many countries, not just in India.

Second, especially post-Galwan and post-Ladakh, public procurement, public contracts, especially infrastructure contracts, awarding these to Chinese companies is politically very risky. Let’s face it. It’s not going to be popular.

Third, in terms of the cost India sought to impose on China post-2020, when China tore up four border agreements going back to the 1990s and placed troops in places it was not supposed to, placed its troops. India had to impose some cost. India had to say that there will be an economic price you’ll pay. What it did was it moved Chinese FDI in India from the automatic route to a route that required additional interdepartmental, inter-ministerial scrutiny on a case-by-case basis. This was done for FDI or foreign direct investment from all countries that shared a land border with India. But quite honestly, it was directed at China because it’s not as if Bangladesh and Pakistan deliver a lot of FDI to India. So, these are the three steps that have been taken.

In addition, as India’s own manufacturing ambitions grow, and I must emphasize here, we are at a very, very early stage, but each step towards building a manufacturing base is obviously seen in terms of how much it means vis-à-vis imports from China. Sometimes this is complicated because as end product lines come to India and are successful in India, component import from China sometimes increases. Diversifying from China sometimes means more imports from China in the short run. Diversifying or de-risking or decoupling, rather, in the time of globalization is not simple and straightforward. It takes a lot of time. So, we are going through a learning process here. But the determination to reduce Chinese dependencies, especially in key, critical areas, is fairly strong.

MADAN: Ashok, I was recalling when you said that this wasn’t new, it was an escalation or emphasis on previous trend lines which got exacerbated or accelerated. And I recall that India withdrawing from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement preceded 2020, it was in 2019.

And unusually, the Home Minister of India, Amit Shah, wrote an op-ed very publicly stating that India’s reasons for doing so was because it did not want to increase those dependencies on China. And there was a sense that essentially RCEP, this agreement, would end up becoming China-India FTA with China exporting even more, with Indian companies having had little access to the Chinese market.

18:15 How does India’s private sector see the de-risking approach?

Ashok, you describe this approach. I sometimes think of it as the D-I-D approach: denial, which is these restrictions: indigenization, which is kind of on-shoring or reshoring; and then the third being diversification as you talked about, or friend-shoring. How is this being seen in the Indian private sector? I know the private sector is very diverse. But how is it generally being seen? Are there certain sectors that like this economic security or de-risking approach, are there others that have concerns about it?

MALIK: I think telecom companies and power companies, in particular, would in an ideal world like to have the option of access to Chinese suppliers because it simply gives them more options. You can look at the Chinese supplier, a Swedish supplier, a Japanese supplier and then play one off against the other and go for the cheapest.

However, they recognize that there is a national hardening of the mood in government and also among publics. And they recognize the risk involved with working with companies such as Huawei. They can’t put their finger to it in every case, but they’ve read and seen too much. They’ve spoken to their peers in other countries to know there are red lines here. So, I think they’re getting used to it.

Like the private sector in the U.S., I think they were behind politicians and behind governments, not ahead of governments in terms of seeking to decouple from China. So, Washington has been ahead of New York. I would say Delhi has been ahead of Bangalore and Mumbai.

But to some degree, this is understandable. Businessmen are not politicians. Businessmen don’t do geopolitics on a day-to-day basis, which is why people like me exist. But I think that they’re beginning to recognize that this is a new world, a world where there will be two systems, there will be two spheres, as it were, one more broadly a more transparent and rules-based sphere, and one a more opaque sphere. One a sphere where India and the U.S., especially in terms of technology, will have more comfort with each other. And one where they will not have comfort with the Chinese.

Second, there’s also a public pushback, which I don’t think anybody really wants to risk or can predict. Because if you have tens of thousands of soldiers at the border, tens of thousands of Indian soldiers and tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers, who obviously mobilized first, you could have a skirmish—I hope you don’t—but you could have a skirmish at any point. And if the skirmish comes bang in the middle of a big business decision you’ve taken, it could boomerang. So, companies are cautious.

I’ll give you one example, which may sound a little silly, but it’s very telling. In 2020 or ‘21, just after the first wave of the pandemic, just after lockdown, just after all of us had locked up at home and were wondering what life had in store for us, the Indian Premier League, the biggest cricket tournament in India, one of the biggest sports tournaments in the world, got off to a delayed start for that year. It was supposed to be played in April, it was played in November later, I can’t remember when.

Now, this came just a few weeks after the Galwan clashes and the death of 20 Indian soldiers, which led to a frisson of emotion across the country, as you can imagine, and a lot of anger against China. The title sponsor for the IPL was a Chinese mobile phone company. Despite the fact that the IPL is very popular, despite the fact that cricket is very popular, despite that fact that after a summer of doing nothing and except waiting at home, people were desperate to see cricket on their television screens. Despite all of that, the public reaction to a Chinese company being the sponsor, the title sponsor of this tournament, was very sharp. It was so sharp that the cricket board had to ask the sponsor to stand down for that year. It stood down for that year, but it’s never come back.

Now, the cricket board and the IPL are ultimately a consumer business. They recognize that there’s a risk. That should tell us something.

22:31 Are Indian tech startups concerned about restrictions on China?

MADAN: And that company, of course, now facing allegations of money laundering as are other companies of evading taxes, amongst other things in India. Ashok, you mentioned Bangalore. I’m sitting in Silicon Valley right now recording this. And one of the things I think both Bangalore and Silicon Valley—Bangalore being India’s Silicon Valley—have recognized is that geopolitics actually does matter.

But I remember when these restrictions were initially imposed, in the startup sector in Bangalore and Hyderabad— they had been getting a lot of Chinese investment coming in. There was some concern amongst the startups in India about the restrictions.

Has that concern continued or have these companies now just realized this is the new normal in terms of India-China ties?

MALIK: I think they recognize that this is the new normal, that if you have Chinese money coming in directly or indirectly—or through a whole network of front companies or shell companies, some based in other geographies outside China, such as Singapore and so on—you will open yourself up to additional scrutiny. You will also open yourself up to a public relations challenge potentially.

So, if you can, you will look for an alternative.

23:48 Has China pushed back on India’s scrutiny and restrictions?

MADAN: You mentioned some of the concerns about China. Another had been looking around the world, China had used its economic ties to coerce countries. We have seen that. When countries have taken moves that China hasn’t liked, whether it was Philippines years ago, whether it was South Korea, whether it was Australia, that there has been this effort at economic coercion. Has there been similar pushback from China to these Indian steps to restrict and impose this scrutiny.

MALIK: This is why China actually has behaved in a strategically puzzling manner. Because if you want a country to be dependent on you, you create reasons for it to want that to become dependent on you and then not be able to shake that habit off. So, for instance, if you look at Australia, Australia has traditionally exported a lot of iron ore resources to China, it’s exported wine to China, exported seafood to China. And China is a very significant export market for Australia. So, when China imposes restrictions on Australian seafood or stops buying Australian wine, it is a big economic hit.

In the case of India, quite honestly, China has imported very little from India. It’s imported commodities and processed those commodities. During the commodities boom in the first decade of this century, it imported a lot of iron ore from India. It continues to do so. It imports some agricultural products, including in fact seafood. It imports some cereals.

But if you look at the quantum of Indian exports to China, I think it’s about 18 or 20 billion. In contrast, Indian exports to the U.S. are about 80 billion. These are figures off the top of my head. It’s about four times, four or five times. So, you know, if India and the U.S. have a bad relationship or the U.S. stops buying from India, we’d be seriously hurt. And the U.S. in that sense has leverage—not that the U.S. will ever go that south, I’m sure. But I’m just giving you a theoretical example. The Chinese haven’t created that sort of leverage.

So, yes, if they stop buying from India, we will lose $20 billion worth of exports. But it’s not that big a market for us as it is for certain other countries.

MADAN: And I think in certain ways, if they could have imposed costs—so take the pharmaceutical sectors where earlier India used to source advanced pharmaceutical ingredients, or APIs, for its global pharmaceutical sector, most of that used to come from India. Over time, that dependence on APIs from China had grown to I think about 60 or 70%.

Now, this wasn’t just a concern for the Indian pharma sector, but also for the U.S., for example, because a lot of pharmaceuticals into the U.S. came from India. So, there was this chain of vulnerability. But when I think about it, if China did cut off APIs to India, it would also suffer because India could then cut off the exports of the pharmaceutical goods that do go from India to China. So, in some ways, one reason we might not have seen China pull that trigger is because the potential for it is negative on their side as well.

27:00 What is the reason for de-risking rather than decoupling?

Having said that, Ashok, we’ve heard the reasons to de-risk and what the Indian government has done. Are there limits to this de-risking effort? What is the reason for de-risking rather than decoupling?

MALIK: Look, China has a very significant economy. It’s a problematic country. It’s got a government which is very unpredictable. It’s got a foreign policy which is totally unpredictable, but it’s still a very significant economy. And it is in a sense a manufacturing power the likes of which the world has not seen in a long, long time, and is unlikely to see in a long time. Even if India becomes a much bigger manufacturing economy, I don’t think we’ll match what China has been able to achieve, which it was allowed to achieve that in a certain period in economic history and good for it.

So, even if India manages to up its share of manufacturing from the current 17 to 18% of GDP to 25% of GDP in the next 10 years, which is the plan here, even if it does that, it will still depend on China for a lot of imports.

Because China is a significant economy and nobody wants to not trade with China. That is ridiculous. There is a difference between my school-going daughter buying a laptop from China and the Government of India buying critical computing equipment from China. The two are very different. My daughter will buy a laptop that is cheap and available. If it’s made in India, well and good. If it’s made in the U.S. or China, [fine]. But that’s different from a strategic purchase.

So, no one wants to hurt Indian consumers by simply by walking away from everything China produces. That’s not the case at all. Of course, it could help if the Chinese were more predictable in both their economic and political approaches, but that’s another matter.

But I think countries will increasingly look for options vis-a-vis China. You spoke about APIs in particular. Post-COVID-19, post the realization that there’s such an API dependence on China, not just for Indian pharmaceutical companies, but for pharmaceutical companies in other countries as well, you are going to see API facilities proliferate in other countries, perhaps in India as well. And certainly that’s the plan here. But let’s presume India does not pull it off and the API ecosystem does not get replanted in India. It will be planted somewhere else. Indonesia has an API plan. The U.S. has API plans, other countries have API plans. So, in 10 years, we will be buying APIs from countries other than China as well. One of those countries could well be India, but there will be others.

So, complete decoupling will not happen, but diversification and de-risking is essential to both economic resiliency and creating some sort of leverage over a China that is just not predictable or stable in its foreign policy approaches.

29:45 Implications of India’s de-risking approach for companies in other countries

MADAN: We’ve talked a little bit about the implications for China and for Indian business for that matter, but what have the implications of this economic security approach that India is taking, this de-risking approach, what have the implications of that been for other countries or companies from other countries, particularly Indian partners?

MALIK: Well, actually companies have seen opportunities in India, especially, again, if you go back to manufacturing, if you go back to electronics, mobile phones, consumer electronics, computers, that range of products where India’s determination to move part of the value chain to this country is very strong, where there is a subsidy and incentive program —to some degree to make up for the absence of factor market reforms in India and the fact that India is still not exactly the cheapest place to produce. That has encouraged companies to look at India.

There’s also recognition that in today’s world, if you want a piece of the Indian market, just as if you want a piece of the U.S. market, it makes sense to have part of your value chain in that country.

And third, if you’re looking at alternatives to China, not moving out of China entirely—nobody is—but alternatives to China, then India offers advantages. So, does Vietnam, so does Thailand, so does the U.S. itself. But India also offers advantages. India is not as cheap as Vietnam, but cheaper than America. India has more engineers than Vietnam. Every country has some plus points. India has plus points as well.

And countries that want to retain market access in broadly the West, or in countries that are in the American sphere of friends, are looking to India because they’re seeing geopolitical signals. They’re seeing the strategic alignment between India and the U.S., and they recognize that this is a relationship that will lead to economic benefits for their companies and economic opportunities for their companies.

MADAN: And of course, to attract some of this investment, and I guess recognizing the opportunity, we’ve seen India also join some kind of U.S. proposed initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the Mineral Security Partnership that a few years ago we might not have seen happen.

32:03 Do Indian companies face restrictions from Beijing due to New Delhi’s restrictions on China?

Speaking of value chains, which you did Ashok, just one follow-up: there has been some concern that companies that aren’t taking their entire supply chains out of China that if they do want to make India part of that value chain that they will face restrictions or constraints because of these Indian restrictions on China. Has that been the case? Have companies faced that issue? Is this something that the Indian government has recognized?

MALIK: To be honest, if you look at mobile phones in particular, it’s been an enormous learning process for business and for government, or for ministries rather, for the government and for various ministries. Because when Apple came to India, it first moved its end product lines to India. It had a very good experience in India, and it makes more phones in India now than it did plan to initially. And that number will only grow.

But, obviously, its import of components—because the component ecosystem has been set up in China over the past 20 years; it’s massive—the import of components from China and from other countries is also big. Now inevitably as component import from China reaches a certain critical mass, some of those components would naturally move to India in terms of manufacture. That would mean FDI from China, technology partnerships with Chinese companies, which are component manufacturing companies. Perhaps they themselves are partnering Western companies and they both want to come to India and find an Indian partner.

There is an inter-ministerial process, which clears such transactions and such proposals. It’s not always smooth. Each one has to offer a justification that it leads to long-term Indian resiliency and promotes manufacturing in India. But permission has been granted, has been given. I’m not saying it’s smooth and automatic. It will not be, nothing with China ever is. If the same component company came from Germany, clearance will come in a minute. Because it’s a China fingerprint, it takes longer. I’m not pretending otherwise. But, frankly, you will find that experience in many countries, including the U.S.

MADAN: And it’s also why we’ve seen people will often criticize or critics will say that, oh, India is saying that it has this economic security approach, but imports from China are going up. That’s actually the case with a lot of countries, including the U.S. where trade is at record highs. And with India, again, China-India trade is at record highs at about $114 billion last year. But what is interesting is that the share of China in Indian imports has already started to fall. It’ll be interesting to see a few years down the line if we see both a slowing of that growth but also see what is being imported change over time.

MALIK: I think that second point you make about what is being imported is more important than the volume of imports. You see, in 10 years, India will be a richer country. So, it will be buying more whatever—jade from China or whatever. So, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. If you’re a richer country, you buy more jade. You buy my family more jade jewelry, whatever it is, that’s fine. But are we importing as many mobile phones and laptops? Or are we importing critical equipment from China? That will be the key test 5 or 10 years down the line.

35:14 Lightning Round: What is the biggest myth you hear about India-China economic ties

MADAN: Ashok, you’ve been very generous with your time in taking us through this journey of economic ties between India and China. I do want to end the way we do all episodes with a lightning round question, which is what is the biggest myth or misunderstanding you hear people talk about when they talk about India-China economic ties?

MALIK: Well, abroad, it’s the sense that economic rupture will cost India enormously, and much more than it actually will, because people think we export a lot to China, and are quite surprised to learn that we don’t, because the Chinese have placed restrictions. And internally, that’s what you referred to some time ago, there’s this very naive and charming perception that decoupling from China or diversifying from China is like putting off a switch; it can happen overnight. The number of policymakers, politicians, civil servants, quite frankly even economists who have that view and need to be educated is significant.

MADAN: With that, thank you very much, Ashok, for joining us on the Global India Podcast

MALIK: Not at all, thanks for having me.

[music]

MADAN: Thank you for tuning in to the Global India podcast. I’m Tanvi Madan, senior fellow in the Foreign Policy program at the Brookings Institution. You can find research about India and more episodes of this show on our website, Brookings dot edu slash Global India.

Global India is brought to you by the Brookings Podcast Network, and we’ll be releasing new episodes every two weeks. Send any feedback or questions to podcasts at Brookings dot edu.

My thanks to the production team, including Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews and Raman Preet Kaur, producers; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; and Daniel Morales, video editor.

My thanks also to Alexandra Dimsdale and Hanna Foreman for their support, and to Shavanthi Mendis, who designed the show art. Additional support for the podcast comes from my colleagues in the Foreign Policy program and the Office of Communications at Brookings.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastIndia’s economic ties with China: Opportunity or vulnerability?

November 15, 2023

Listen on

Global India Podcast