If immigration reform is dead, is that bad news for social mobility and the American Dream? Eric Cantor’s surprise primary defeat has widely been attributed to his stance on immigration: the conventional political wisdom is that his defeat signals the end of any chance of immigration reform passing.

Immigration and upward mobility co-exist in the American imagination. With little more than their wits and their ambition, new Americans from Andrew Carnegie to Arnold Schwarzenegger have flocked to our shores, and worked their way up. But what do the data tell us?

We decided to revisit and update the data presented in Brookings’ 2008 report, Getting Ahead or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America on the educational attainment, wages, and intergenerational mobility of immigrants.

Not all immigrants are low-skill, low-education workers…

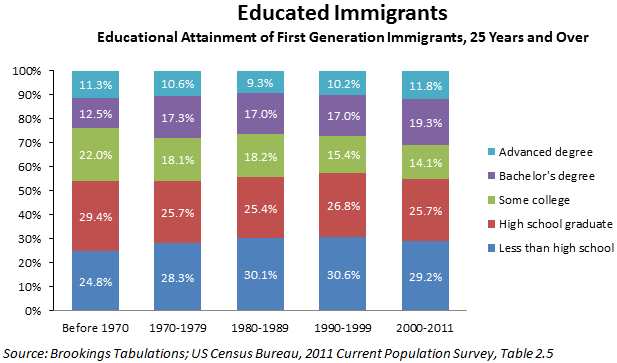

First point: for all the fears of a flood of unskilled workers into the United States, it looks like the educational attainment of immigrants has not changed much in the last fifty years. Immigrants with less than a high school education have made up about 30% of the country’s immigrants consistently for over 40 years.

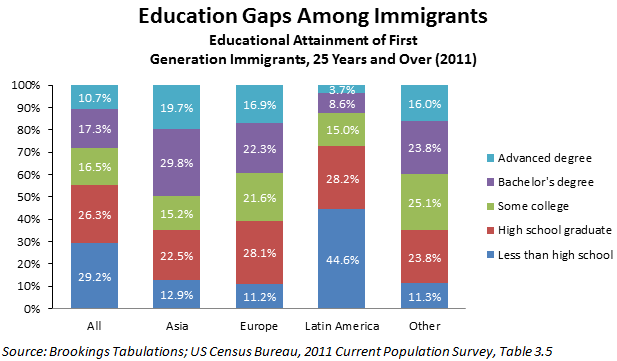

Educational attainment varies by the immigrants’ region of origin, however. Immigrants from Latin America are less likely to have the equivalent of a high school diploma, while Asian and European immigrants are more likely have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Children of immigrants are exemplars of the American Dream

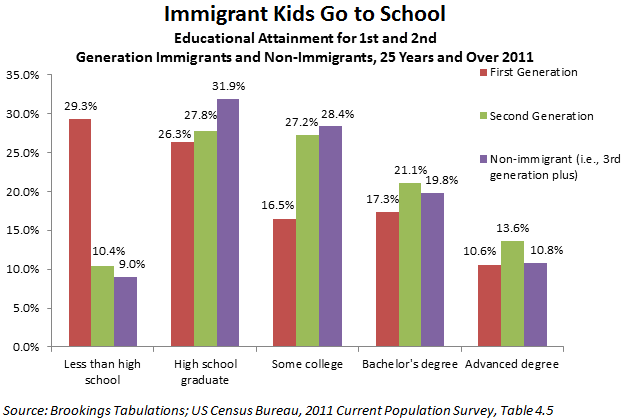

Second-generation Americans’ educational attainment is much higher than their parents. In fact, second generation Americans are more likely to get college or advanced degrees than non-immigrants:

Again, there are ethnic differences here: the children of Asian immigrants typically have very high educational attainment levels, bringing up the average level of educational attainment for all immigrant children, whereas the children of Latin American immigrants typically have lower educational attainment than non-immigrant children.

But this is not to say that the second-generation Latin American immigrants have been less successful in seizing the American Dream – while they have low levels of education compared to the country as a whole, they have nonetheless far surpassed their parents.

Measuring mobility for immigrants

Social mobility for first or second generation immigrants is an area of research that is unfortunately underdeveloped. The bulk of research on social mobility relies on having access to the income or occupation of a parent generation, but when the parent is an immigrant, this may not be available or may not be easily comparable to US data. As such, immigrants are often not included in estimates of mobility (for example, our Social Genome Model at Brookings is restricted to non-immigrant children). But understanding how immigrants fit into the mobility conversation is not a question that can ignored. Tomorrow we’ll take a stab at examining what we do know about social mobility and opportunity for immigrants and their children.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Immigration and the American Dream, Part 1

June 19, 2014