Studies in this week’s Hutchins Roundup find that misdiagnosing the slowdown as lack of demand than supply has led to adverse economic conditions, universal access to Medicare improves health and more.

Want to receive the Hutchins Roundup as an email? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every Thursday.

Misdiagnosing economic slowdown has led to adverse economic conditions

What explains the slow growth in GDP, low investment rates, and low interest rates in advanced economies in recent decades? A common explanation is a lack of aggregate demand, and that has led central banks to lower interest rates. Bas Bakker of the IMF argues that, if weak demand were the culprit, unemployment rates would have been increasing; instead, they’ve been falling. He posits that the slowdown is instead a result of a reduction in supply, or potential output, caused by a slower growth rate of workers and productivity. He finds that an aggressive central bank easing in the face of a decline in potential output may increase gross investment, but it will not increase net investment. Moreover, low interest rates lead to an increase in the capital-output ratio, a low return on capital, and high leverage. He argues that this pattern matches the experiences of major advanced economies in recent years.

Universal access to Medicare improves health

Rebecca Myerson of the University of Wisconsin Madison and Dana Goldman, Darius Lakdawalla, and Reginald Tucker-Seely of University of Southern California find that access to Medicare at age 65 increases cancer detection and lowers cancer mortality. Using data on cancer registries for breast, colorectal, and lung cancer from 2001-2015, the authors find that detection rates for those just over age 65 exceed those for adults just under age 65 by 11%. Access to Medicare lowers cancer mortality for women by 4.5%, but has no effect for men. Black women experience a particularly large decline in cancer mortality at age 65, possibly due to the larger impact of Medicare on access to health care for racial minorities, the authors say. However, the authors find no significant change in cancer detection or mortality among Black men.

Government-sponsored enterprises are implicitly providing insurance for climate risks

Amine Ouazad of HEC Montreal and Matthew Kahn of Johns Hopkins University find that government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) – Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — are implicitly insuring homes against risks related to climate change. The GSEs buy mortgages that meet federally set standards (conforming loans) from lenders. The authors reason that because lenders can sell their mortgages to the GSEs, they are less likely to screen or price mortgages for climate risk—for example, the risk of default associated with flooding in coastal areas. Using mortgage-level data and natural disaster events between 2004 and 2017, and comparing mortgages just above and just below the loan limits for conforming loans, the authors find that the difference in denial rates for applications for conforming loans and non-conforming loans increases by 5 percentage points following a large natural disaster. Furthermore, the volume of lending right below the conforming-loan limit increases, and the performance of those loans deteriorates, suggesting lenders shift risk to the GSEs. For lenders to properly account for climate risk, the authors argue, GSEs could withdraw from the mortgage market in risky areas or charge lenders for climate-change related risks.

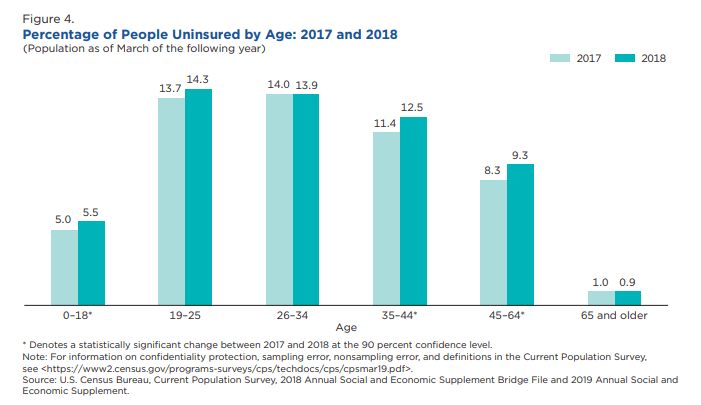

Chart of the week: Rate of uninsured people rises for most age groups

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

“All instruments from interest rates to asset purchases to forward guidance are ready to be calibrated. We also need to reiterate that we are symmetric in pursuing our objective, i.e. that to keep inflation above our target as much as below it. Also, in the future, if the experience is telling us anything, it is this: we have to have a fiscal policy of some significance in the Eurozone. The first time I mentioned this was in a speech I gave in Jackson Hole in 2014 and I repeated it thereafter several times. I always mention the fact of the need to move from a rules-based national fiscal policy to an institution-based fiscal capacity. We have countries that have fiscal space and don’t use it. Even if they were to do something, what would be useful to the rest of the euro area would only be the spill-overs. This means that steering the aggregate euro area fiscal stance in an optimal way through decentralized policies is difficult to achieve given that national policies are geared to national stabilization needs,” says Mario Draghi, President of the ECB

“Furthermore, what is clear is that the current composition of euro area fiscal policies is not optimal. Countries with fiscal space could use some of it to strengthen public investment and increase their growth potential. Member states with high debt with few exceptions are not building buffers needed to provide fiscal stabilization during the next downturn. […] Monetary policy can do its job, but in the absence of a stabilization capacity it will only do it more slowly and with more side effects. A combination of monetary and fiscal policies might have delivered similar results on growth and inflation, but faster and at a higher level of interest rates.”

Commentary

Hutchins Roundup: Misdiagnosing economic slowdown, Medicare, and more

October 3, 2019