If you’re like me and my colleagues here at Duke University, you don’t know what to make of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI is the new acronym, the old one was OBOR for One Belt One Road). Is it just a way for China to put its excess construction workforce, steel and cement production, and burgeoning bank balances to work, or is it the first part of a grand plan to take over the role of hegemon? Is it both, or something else? I’m going to recommend some readings that might help you make up your mind.

Though it was launched in 2013, these are early days for BRI, and much of what’s out there is journalistic stuff. So don’t expect rigorous analysis. But I plan to use this blog to keep readers informed about the BRI, and you can expect reads that are progressively more serious.

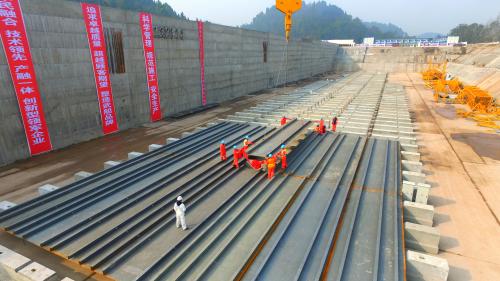

Figure 1: The Belt (red) and the Road (blue)

What is the Belt and Road Initiative?

This is the official explanation by China’s National Development and Reform Commission, the lead agency for the BRI.

This article by Geoff Wade provides a crisp summary of the initiative, calling it “a Chinese economic and strategic agenda by which the two ends of Eurasia, as well as Africa and Oceania, are being more closely tied along two routes—one overland and one maritime.” While it formally covers greater development cooperation, infrastructure networks, trade, financial cooperation, and cultural exchanges, infrastructure is getting all of the attention.

More than 65 countries have signed on. This article has a map that shows the members of the BRI: essentially every country in Asia and East and Central Europe, except for Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. Participant countries have more than half the world’s population and about a third of global GDP. Annual investments of about $150 billion are envisaged for the next decade. At the Belt and Road Forum in May, China pledged about $125 billion in financing.

China is putting a lot of money into the BRI. In 2016 China reportedly made about $30 billion of acquisitions in BRI countries; this year, it has already made more than that. This is at a time when the government has been discouraging offshore acquisitions by Chinese firms. Regulators have obviously been told to prioritize BRI investments.

The BRI is not to be confused with the China-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. David Dollar explains the difference. The AIIB was launched in 2016 and has 56 member countries (Australia, New Zealand and South Korea are members). The AIIB is just one of the financial institutions funding investments that are part of the BRI.

The Heritage Foundation advises U.S. policymakers to watch out. Developments in Central Asia are especially telling: China’s trade with the five Central Asian states (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) is already more than double their trade with Russia.

What does China expect to get out of it?

The Economist explains what’s in it for China.

“Its ultimate aim is to make Eurasia (dominated by China) an economic and trading area to rival the transatlantic one (dominated by America). Behind this broad strategic imperative lie a plethora of secondary motivations…. By investing in infrastructure, Mr. Xi hopes to find a more profitable home for China’s vast foreign-exchange reserves, most of which are in low-interest-bearing American government securities. He also hopes to create new markets for Chinese companies, such as high-speed rail firms, and to export some of his country’s vast excess capacity in cement, steel, and other metals. By investing in volatile countries in central Asia, he reckons he can create a more stable neighborhood for China’s own restive western provinces of Xinjiang and Tibet. And by encouraging more Chinese projects around the South China Sea, the initiative could bolster China’s claims in that area (the “road” in “belt and road” refers to sea lanes).”

David Dollar explains why China considers it urgent. In the six years before the financial crisis, the Chinese economy was growing at 11 percent each year with an investment to GDP ratio of just over 40 percent. In the six years after the crisis, the growth rate has averaged 7 percent with an investment-to-GDP ratio of 50 percent. The Chinese are justified in finding ways to grow more efficiently, and the BRI should be seen as the external component of the strategy; the domestic agenda is equally complex.

What should others do to make the most of the initiative?

About a year ago, the Economist Intelligence Unit provided what I thought was the most comprehensive country-by-country list of activities that could be included in the BRI. It is mostly about infrastructure.

What should get a lot more attention are the social, environmental, and political implications of the BRI for the countries that benefit from greater infrastructure investments and increased road, rail, and sea traffic.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Future Development Reads: China’s Belt and Road Initiative

September 22, 2017