Under the threat of COVID-19, life as we know it is unravelling across the world. Political developments considered momentous only a few weeks ago now appear trivial. In France, one of the big questions for 2020 was the ability of President Emmanuel Macron’s political movement, La République en marche (LREM), to gain a much-needed local foothold in the March municipal elections.

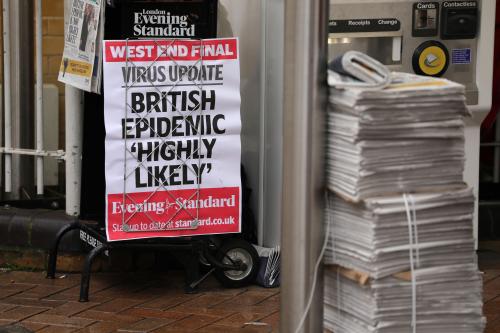

But the health crisis that has engulfed our societies, including France, appears to be turning politics-as-usual upside down, rendering the need for democratic consultation moot, at least for now. The political battlefield has shifted towards public health policy, crisis management, and executive leadership. Peacetime politics have been replaced by angry debate on how to conduct the war against COVID-19.

Politics before the war

After Macron was elected president in 2017 on the ashes of the French party system, he built LREM from scratch and took risks by promoting political newcomers. This has led to somewhat dissonant ideologies among members, and more than 15 MPs have left the party since the election. Yet French politics have remained atomized: Not only is the opposition to Macron fragmented, but the president’s party maintains a weak hold on power (recent opinion polls put the president’s popularity at 33%).

A year and a half into his mandate, the Gilets jaunes, a leaderless protest movement against social and fiscal injustices, underlined the fundamental disconnect between Macron’s party and “peripheral France” — the struggling lower and middle class beyond the beltways that surround large cities like Paris or Lyon. Macron’s attempt to reform the pension system also faced an angry opposition, triggering month-long strikes that paralyzed Paris.

Hence the importance of this year’s municipal elections, which presented an opportunity for a referendum on Macron two years before the next presidential election, and a test of his viability outside the capital. Several races, including over control of Socialist-led Paris, attracted significant attention. In mid-February, all eyes were fixed on the precipitous withdrawal from the race of the LREM candidate for mayor of Paris, a major development at the time that now looks inconsequential.

Three days before the first round, scheduled for Sunday March 15 — as COVID-19 was already claiming lives in France — President Macron announced school closures, but confirmed that the municipal elections would nonetheless take place. Party leaders across the political spectrum acquiesced. Earlier that day, when rumors had begun to circulate that the elections might be postponed, the head of the center-right party Les Républicains, Christian Jacob, denounced the idea as a “coup d’état” conjured by the president to protect his party from a “debacle” at the polls.

Over the next two days, preparations for the election continued as though the number of COVID-19 infections in France was not doubling every four days. Despite governmental restrictions on mass gatherings, hundreds of Gilets jaunes took to the streets for the 70th consecutive Saturday, leading to violence and arrests. As France transitioned from stage 2 to stage 3 of the pandemic, it decreed the closure of all “non-essential public places,” but Prime Minister Édouard Philippe reiterated that the following day’s municipal elections would proceed “as planned.” Citizens were urged to bring their own pens, maintain a one-meter distance from other voters, and wear masks so long as they remained recognizable.

Meanwhile, however, the public’s threat perception increased exponentially. Older voters, who are more vulnerable to the virus, chose to stay home, and the abstention rate reached a record 55.36%, 20 points higher than in the previous municipal election in 2014. As a consequence, election results were muddled and hard to interpret. It quickly became clear that LREM had performed poorly, capturing few municipalities and finishing third or fourth in major cities such as Paris, Lyon, and Marseille. Europe Écologie les Verts (EELV), the French Green party, made some gains — outperforming in Lyon, Grenoble, and Strasbourg — and the far-right Rassemblement National confirmed its hold on several cities. Yet no overarching political narrative emerged.

By the time the results of the first round came out, alarm over France’s coronavirus outbreak was accompanied by public anger. The number of cases was rapidly mounting, and suddenly, political leaders from all parties — most of whom had previously agreed with Macron’s Thursday decision to proceed with the elections — were calling for the second round to be postponed. Even Macron’s last-minute candidate for Paris, the former Health Minister Agnès Buzyn, confided in a controversial interview that she thought the first round should not have taken place.

Twenty-four hours after the polls closed, the French president announced a period of full confinement in France — meaning that citizens could only leave their residences with proper certification — and the postponement of the second round of municipal elections until at least June. It became clear that, in the age of COVID-19, the spread of infections across Europe, and France, followed by an avalanche of decisions taken to mitigate and contain the crisis, would override all other concerns, including politics. “We are at war,” the president solemnly declared.

Politics of war

President Macron’s announcement elicited relief across party lines. In fewer than four days, the entire political class had shifted gears, calling for unanimous, razor-sharp focus on the crisis, thereby seemingly distancing itself from political controversy. Although the Assemblée Nationale itself had become a hot-bed for infection, it spent the week following the first round of elections passing a law instituting a national “state of sanitary emergency,” which grants the government exceptional powers to deal with the crisis for the next two months.

“This is a war,” President Macron repeated in an address outside of an army-built clinic in Mulhouse on Wednesday. To combat the virus, the government drew on the “sanitary reserve”: 40,000 healthcare professionals (retirees, students, and others) to lend a hand to overextended medical staff. The military has also been mobilized: Operation Resilience allows Macron to deploy French troops throughout the country in support of public services, and to send helicopter carriers off the coasts of overseas territories.

During the war against coronavirus, should politics be cordoned off entirely? They evidently won’t be, not in a democracy, and especially not in one as fragmented as France. Despite apparent unity over the declaration of the state of emergency, the gloves have since come off.

Marine Le Pen, Macron’s far-right opponent in 2017, who had expressed approval of his aggressive quarantine measures and closure of borders, has since resumed her accusations that the government has misled the public about the pandemic. On the left, Olivier Faure, first secretary of the Socialist Party, openly questioned the government’s capacity to manage the crisis. Even Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the founder of the far-left La France Insoumise, who had been refraining from criticism, chimed in to point out the “flaws in the machinery of government.” And while President Macron announced the suspension of most reform projects for the duration of the epidemic, Gilets jaunes took to their balconies a week after the election for a coronavirus-appropriate 71st Saturday of protesting.

The power of opposition politicians is limited in times of such grave crisis. Discussing tactics during a war about which you have little field information and against which you have no weapon is risky. And with the country under lockdown, the opposition cannot take to the streets, the preferred mode of action in France. So opposition politicians are sticking to cable news and social networks, where disinformation and conspiracy theories proliferate. Those who want to appear credible tread lightly: The Socialist Party Leader Olivier Faure sent a letter to the president asking for a “war economy” that would allow the government to order factories to produce masks. Leaders from the center-right Républicains have called for an official parliamentary inquiry into the state of preparedness before the crisis. Confined members of parliament are taking advantage of the period of self-isolation to virtually reconnect with constituents.

But in a war-like state, the only decisions of consequence are those made by the executive branch — and not just in Paris. Even in the centralized French state, the crisis has shifted the spotlight to officials with territorial authority — prefects, mayors, and regional presidents — who have a degree of discretion to execute policies within their jurisdictions.

The news media are also giving a platform to scientists from the Conseil Scientifique (a newly created body to advise the Elysée on the pandemic), as well as union leaders and heads of professional associations in areas like healthcare, distribution, agriculture, utilities, and transportation. With public outrage growing over the shortage of masks and protective gear, as well as lack of testing, doctors’ unions have appealed to the Conseil d’État, the top administrative court in France, which has rejected their claims so far. Nonetheless, healthcare professionals are enjoying newfound political power: The government has finally vowed to meet the needs of the hospital sector — which has been in disarray for years — through a massive investment plan after the crisis, and in the meantime, immediate financial support for this first line of defense against COVID-19.

For anyone who is not in the business of executive leadership, healthcare, or supportive functions, the war against COVID-19 calls for humility.

In addition, the French government has implemented major economic stabilization measures through its 45 billion euro package to help companies and employees get through the crisis. Measures include relaxing French labor laws and deferring corporate and payroll taxes. The government also created a state-guaranteed fund of 300 billion euros for bank loans to companies, and asked companies not to pay dividends this year. But while the French government pushes for greater solidarity at the European level to relaunch the economy after the crisis subsides, the war in France is being fought mainly against death, not recession.

Unsurprisingly, then, French citizens are wrought with pessimism and anxiety. Sixty-five percent believe that Macron and his government are “not doing enough,” and 47% report feeling anger about the president’s management of the crisis. Even the expected uptick in the president’s popularity is actually fairly small given the circumstances. But no one is benefitting: Only 27% of French people consider opposition parties “up to the task” of dealing with the pandemic, whereas mayors and prefects fare much better, with 69% and 50% respectively. With anxiety rising amongst overly-vigilant citizens stuck at home, politics has stumbled into unchartered territory. For anyone who is not in the business of executive leadership, healthcare, or supportive functions, the war against COVID-19 calls for humility.

Commentary

France at war against the coronavirus: Politics under anesthesia?

March 31, 2020