Like all immigrants, Bosnians who live in Austria are attached to their homeland. Today, with improved road connections, many can drive to their native country (where they often own a spacious family home) in some 6-8 hours.

Many cities in the world are grappling with congestion and rising rents. But in Bosnia, as an Austrian-Bosnian recently explained to me, demographic decline is having the opposite effect, with devastating consequences. He owns a spacious family home of about 250 square meters with a large garden, outside of Banja Luka, the country’s second largest town. If he sold it now, he thinks he could ask at most 15,000 euros for it. Why so low? Because the country, and particularly the secondary towns, are steadily losing people. He would rather give the house away for free or destroy it than sell it for so little.

This example from Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) illustrates how the world’s demographic trends are diverging. While we are still experiencing rapid population growth at the global level (of around 80 million people per year), an increasing number of countries are losing people continuously. This is especially true in Europe, where Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the most extreme examples. By some estimates the country lost one-third of its population since the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

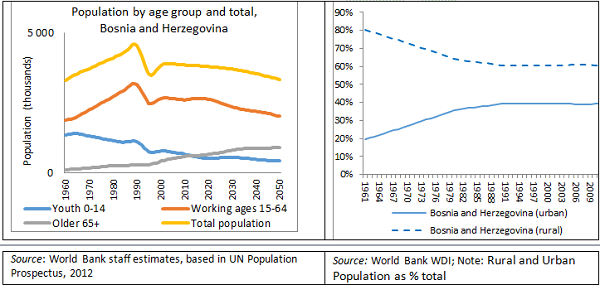

BiH is not only shrinking, it is also aging. In 2015, for the first time in its history it will have more old people than young people (figure 1). A rather unusual feature for a middle-income country is Bosnia’s high share of the population still residing in rural areas (figure 2): cities are not as dynamic as they could be and villages are not turning into towns. This, in turn, reflects a lack of economic dynamism in the country and many Bosnians, who receive only a basic income (often from social or family transfers), can afford a (relatively) better life in villages, where prices are lower than in cities.

Figure 1 Shrinking and aging …. Figure 2. … while remaining rural.

For BiH, a middle-income economy where life expectancy stands at a relatively high 76 years on average and deep poverty remains rare, the main challenge is to overcome the sense of stagnation that the country has fallen into over the last decade, reflecting a lack of economic opportunity and decent jobs (see yesterday’s blog).

Higher fertility won’t solve the problem. Even if there were a sudden turn-around in fertility it would take at least two generations to bring Bosnia’s population levels back up to where it was in the early 1990s.

There are four key policy areas where Bosnia and Herzegovina would need to act to secure a better future for the next generation:

- First, the main challenge is to revive cities. Though many people are rural, their opportunities actually depend on being connected to thriving cities. The more vibrant the cities the more jobs there will be for everyone, including those who still live in rural areas today.

- Second, BiH needs to find a better balance between in-migration and out-migration. It is normal that talented people move elsewhere to gain international experience. However, successful emerging economies must find a way to either attract them back or get talent from other parts of the world.

- Third, shrinking settlements need to be managed to ensure they are still livable. This may require knocking down old houses or redesigning public spaces, as has happened in Pittsburgh or Dessau in Germany.

- Fourth, service delivery mechanisms need rethinking so that services remain accessible to people in smaller settlements and also affordable for the state. Innovations in fields such as tele-medicine and interactive distance learning are particularly promising for countries in demographic decline.

My home country Germany also offers a few lessons. It is shrinking, but its bigger cities are booming, partly because the government has now accepted that the country needs immigration of skilled and motivated people from elsewhere, including Bosnia.

Commentary

Four lessons from Bosnia and Herzegovina on turning around demographic decline

July 1, 2015