Below is an adapted viewpoint from Chapter 1 of the Foresight Africa 2018 report, which explores six overarching themes that provide opportunities for Africa to overcome its obstacles and spur inclusive growth. Read the full chapter on African leadership here. This viewpoint was written on January 11, 2018, prior to recent developments in the country.

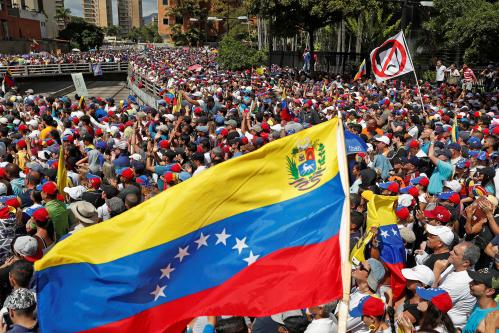

The year 2018 will see general elections in at least 15 African countries. Although many African countries have, during the last several years, strengthened their democracies, the rise of ethnic-based political parties has become a major challenge to electoral processes. Like Kenya’s 2017 presidential elections, electoral contests in countries such as South Sudan, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Mali are likely to involve some level of sectarian conflict, especially given the rise of identity politics.

The Kenyan general elections, which took place over August-October 2017, offer a few lessons on how to deepen, institutionalize, and sustain democratic governance. Kenya is a relatively stable and mature democracy, and an economic powerhouse in a region beset by seemingly insoluble sectarian conflicts, dysfunctional governments, and humanitarian crises. The 2017 general elections tested Kenya’s democratic system, which is undergirded by a separation of powers with checks and balances. Kenya is also a key player in many regional organizations, such as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, that play an important role in regional conflict resolution. The country is an important regional partner in international efforts to fight terrorism and extremism as well as sectarian violence, with its capital, Nairobi, serving as regional headquarters for many regional and international organizations. Finally, as the leading economy in East Africa, Kenya can help neighbors, such as South Sudan and Somalia, escape their underdevelopment traps. Thus, anyone concerned about peace, security, and human development in Africa generally and East Africa in particular, should be interested in governance and constitutional issues in Kenya.

How did we get here?

After the August 8, 2017 general elections, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) declared incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta the winner with 54.17 percent of the votes. Opposition leader Raila Odinga argued that the presidential election had been marred with irregularities and that the results “were hacked and rigged in favor of the incumbent, Kenyatta,” despite international observers’ assessment that it was “free and fair.” Odinga and his coalition, the National Super Alliance (NASA), appealed to the country’s Supreme Court.

On September 1, 2017, the Kenyan Supreme Court overturned the presidential elections and ordered a re-run election to be held within 60 days. Reactions to the court’s ruling were swift: Odinga and his supporters welcomed the decision, while Kenyatta expressed both anger at the ruling and willingness to respect it, and called on Kenyans to respond peacefully.

Preparations for the re-run election were, however, marred by controversy. Odinga’s opposition coalition argued that the October 17, 2017 date for the re-run election did not provide the IEBC with enough time to prepare for a credible election. After the IEBC moved the date up to October 26, 2017, Odinga still refused to participate because “his party lacked confidence in the credibility of the process.” On election day, turnout was extremely low—less than 35 percent of registered voters participated. In addition, according to some Kenyans, including Martin Kimani, the director of the Kenya National Counter Terrorism Center, the opposition and its supporters had “provoked the violence,” even preventing voters from taking part in the election in four counties in western Kenya, an opposition stronghold.

Although IEBC officials had warned that political interference was threatening to derail the rerun election, when the results were announced on October 30, 2017, the IEBC, declared the process “free and fair.” Kenyatta, the only serious contender, captured 98 percent of the votes.

Only a country’s citizens can make its democracy and government work.

Odinga immediately rejected the results, characterizing them as a “mockery of elections,” but decided not to challenge them in court as he had done previously. Although the results were challenged in several petitions to the Supreme Court by private citizens, all six justices unanimously voted to dismiss them, and, on November 20, 2017, the Supreme Court ruled that the re-run election had “met all the constitutional requirements, meaning that incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta is the winner.” Since then, Odinga has emphasized that, “no matter what the courts [have] said, he would not accept the results [of the election] and [would] not accept Uhuru Kenyatta as the legitimate president” of Kenya.

The opposition, like many Kenyans, is at a crossroads—if it rejects the Supreme Court’s latest ruling and proceeds to act extra-constitutionally and swears in Odinga as it has threatened, it will be admitting lack of respect for the judicial system. Odinga called off the swearing-in of the so-called “People’s President,” which was supposed to take place on Tuesday December 12, 2017 and the international community praised his decision, considering the move as a positive step towards national reconciliation.

Kenya’s experience offers Africans important lessons on the role that leadership, good citizenship, and strong democratic institutions can play in fostering a peaceful democratic process.

Lessons for 2018

First, acknowledge the rights and grievances of all citizens, not just those of supporters

No matter who ultimately wins an election, all political actors must acknowledge the anxiety of those, including minority ethnic and religious groups, who feel marginalized. In Kenya’s neighboring countries, such as South Sudan and Somalia, many groups that perceive themselves as marginalized have resorted to sectarian violence. The perception that the state is not providing all groups with opportunities for self-actualization is a major issue that must occupy the efforts of any government. Political and economic participation, as well as the creation within each country of an institutional environment within which citizens can organize their private lives must be a top priority for all governments and members of the opposition.

To foster political and social unity, in 2010, Kenyans enacted a new constitution with the goal of binding the country’s subcultures through common ideals and shared values. Nonetheless, many citizens still feel marginalized.

Kenyatta announced during his inaugural address that his government would encourage unity based on a common citizenship and the values enshrined in the country’s constitution. He also committed to serve all Kenyans, be “the custodian of the dreams of all,” and “the keeper of the aspirations of those who voted for me and those who did not.” If Kenyatta is able to keep this promise, he will set a standard for many other African politicians.

Second, protest, but respect the laws and institutions of the land

The opposition must also take responsibility not to engage in extra-constitutional practices. Nurturing secessionist ideas and fomenting unrest undermines efforts by citizens on both sides to participate in nation-building. It is incumbent upon political elites to explain “the facts of life” to their constituents and emphasize that failure to consolidate peaceful coexistence will be detrimental for all. Mr. Odinga’s decision last year to call off the opposition’s ceremony to establish a so-called people’s government is a step in the right direction.

At the same time, in a democratic system, citizens must be allowed to exercise their constitutional rights to protest peacefully and benefit from the protection of the law. During Kenya’s elections, law enforcement officers were criticized for brutally suppressing opposition protests.

Third, encourage participation in the process by all citizens

Only a country’s citizens can make its democracy and government work. While boycotting elections, as did Kenya’s opposition, is the right of every citizen, it is important that all citizens understand that participation is the key to an effective and fully functioning democratic system. Constitutional checks and balances alone are not enough to prevent government impunity. What has been referred to as “social checks and balances” are quite critical too.

Fourth, fight corruption and halt the misuse of power

Impunity at the hands of the state remains a major concern across the continent. Corruption and political opportunism do not augur well for each African country; in fact, these behaviors, left unchallenged, create dysfunction and distrust in government.

In recent years, many African countries (e.g., Cameroon, Kenya) have enacted legislation to strengthen the ability of the government to fight terrorism and religious extremism and promote law and order. Unfortunately, in many of these countries, these laws have been used to muzzle the free press, silence critics, and suppress dissent. Even before Kenya’s security forces were accused of brutally suppressing demonstrations in 2017, their anti-terrorism tactics had come under fire for allegedly violating the rights of many Muslim citizens.

The supremacy of law is the heart and foundation for a democracy; it is the mark of a free society; it is the most important characteristic of a governance system.

Fifth, respect and protect the independence of the courts

Kenya’s recent experience has helped to preserve the separation-of-powers regime, and the checks and balances enshrined in the constitution. During this tumultuous period, the Kenyan judiciary proved that it has the capacity and the wherewithal to act independently. In constitutional matters, there must be a final authority, one whose judgment must be respected by citizens. While citizens may disagree with such judgment, they must, nevertheless, respect it. Kenyatta’s decision to accept the ruling to nullify the election was historic and paves the way for more respect for the rule of law across Africa.

For Africa’s judiciaries to serve as effective checks on governments, they must be independent. Minimum requirements for judicial independence include “security of tenure,” “financial security,” and “institutional independence with respect to the judicial function.” Judicial officers must also be guaranteed a safe working environment.

The way forward for Kenya and other African countries with significant levels of ethnocultural diversity is for elites to form political parties that transcend ethnicity.

Sixth, inspire civil servants to lead by example and embrace diversity

Democratic institutions, including the Supreme Court, are the foundation and basis of a free society. The face of these institutions are the people who serve in them. In leading by example, civil servants and politicians must exhibit the highest levels of civility, professionalism, tolerance, fairness, and integrity. Public servants must value and respect dissent and diversity of opinion. This approach to public discourse is important in Africa where citizens quite often do not trust public institutions, especially those led by members of another ethnocultural group.

The way forward for Kenya and other African countries with significant levels of ethnocultural diversity is for elites to form political parties that transcend ethnicity. The deepening of democracy demands significant political competition across ethnocultural divides. Across Africa, the ethnic group will remain an important institution, but it should be de-emphasized as the foundation for political organization and a major factor in public policy. To address these concerns, some countries (e.g., Rwanda) have attempted to eliminate ethnic differences and prohibit references to ethnicity in public life. That approach, unfortunately, may not be effective.

Finally, safeguard the rule of law

All political leaders and their supporters must understand that the rule of law cannot function in a country unless a majority of the citizens voluntarily accept and respect the laws. As Kenyatta said in his inauguration speech, “[h]owever serious our grievances, the law must reign supreme. That law should be the refuge for every Kenyan. None of us should break outside the law, or constitutional order, whatever our grievances or protestations.” The supremacy of law is the heart and foundation for a democracy; it is the mark of a free society; it is the most important characteristic of a governance system.

In 2018, we hope that African countries holding general elections will reflect on these lessons and hold peaceful, fair, inclusive, and credible elections and that any election related conflicts will be resolved peacefully through the courts and not violently on the streets.

Commentary

Foresight Africa viewpoint – Elections in Africa in 2018: Lessons from Kenya’s 2017 electoral experiences

February 1, 2018