In 2012, over one in five U.S. children lived in households that were food insecure, defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited access to food.” The definition is derived from a series of 18 questions in the Core Food Security Module that ask whether the household faced difficulties feeding adults and children over the past year because of lack of money.

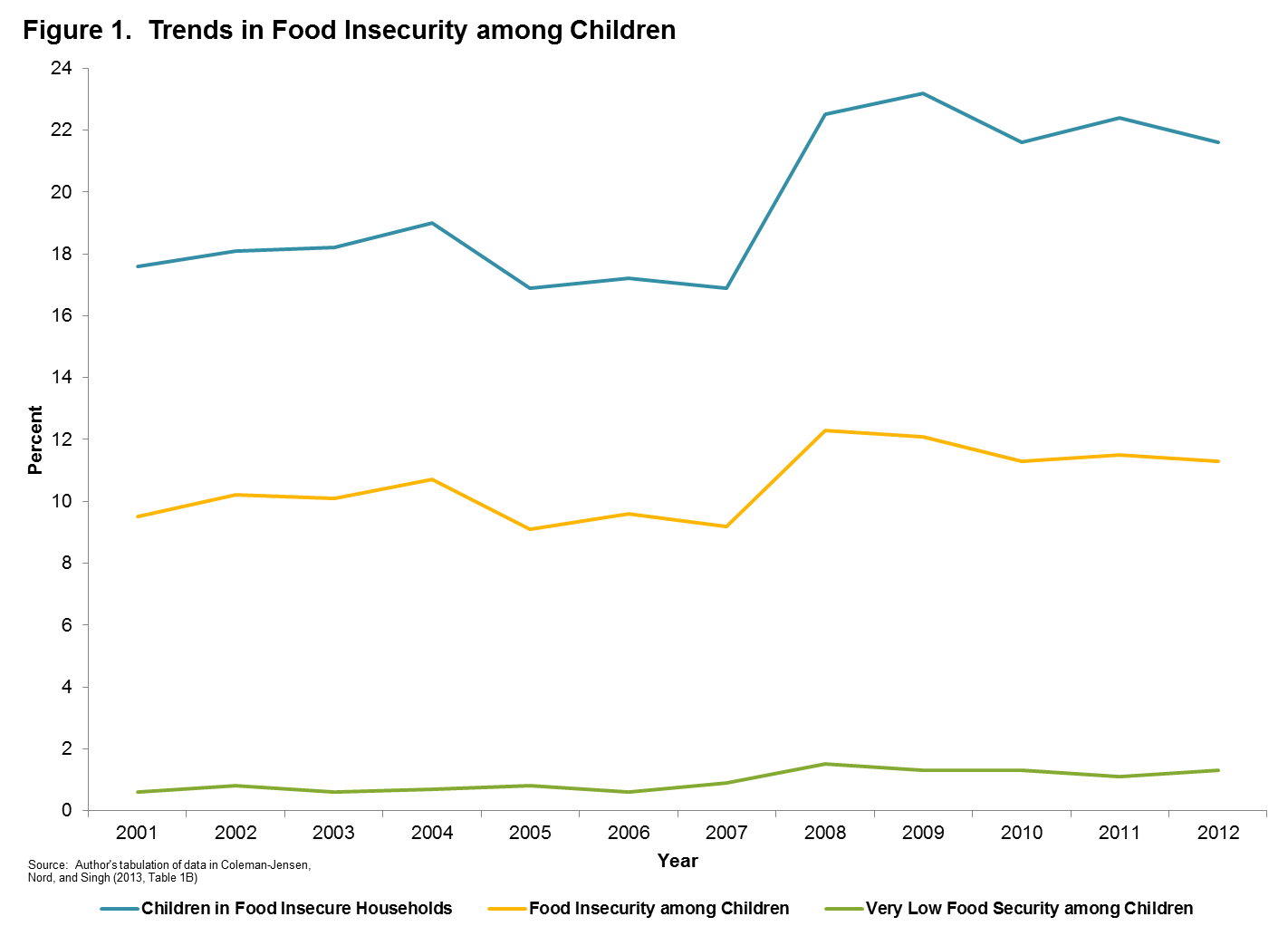

As shown in Figure 1, food insecurity levels for children saw a substantial increase during the Great Recession and have not improved much since then.

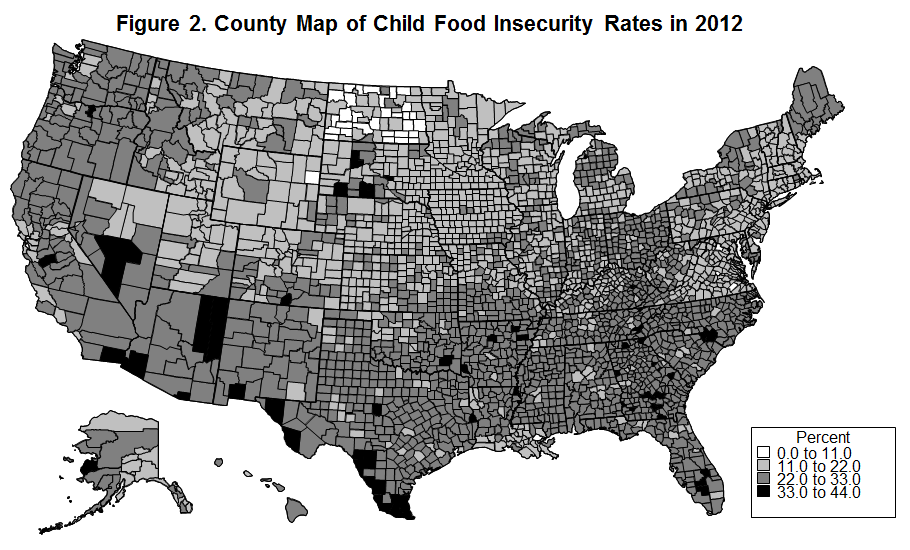

Some areas of the country face higher levels of food insecurity than others (figure 2). Insecurity is worse in the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia, the Rio Grande, and on American Indian reservations.

Who is Food Insecure?

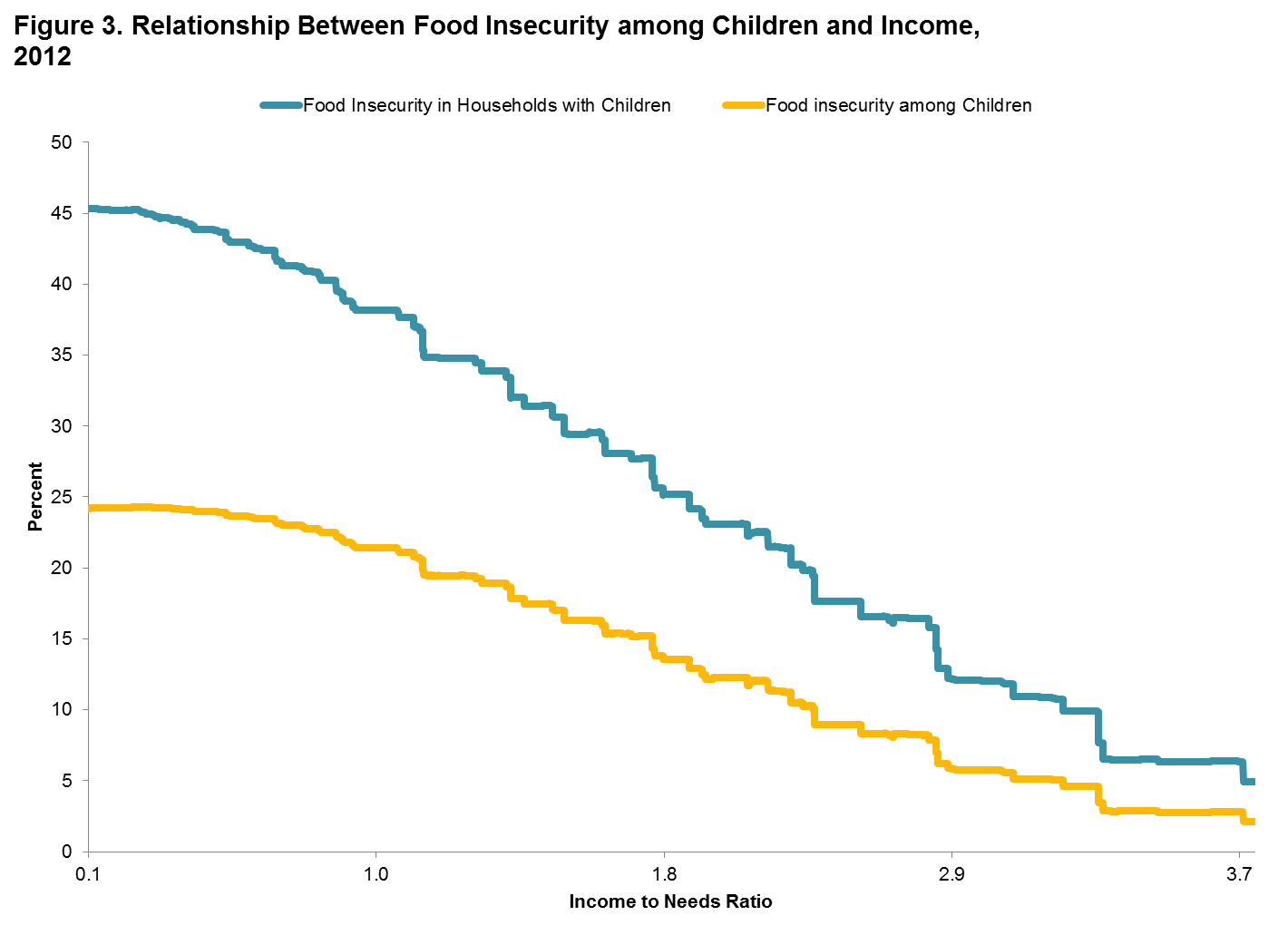

Unsurprisingly, income and food security often go hand in hand (see Figure 3). Around 40 percent of children in households near or below poverty are in food insecure households.

But even at incomes two or three times the federal poverty line, food insecurity is not uncommon, suggesting that income is only one factor contributing to food security. Our review of the literature suggests that there are five key factors that influence food security:

-

- Parental mental and physical health: Growing up with a parent with physical disabilities, depression, or substance abuse significantly increases the likelihood that a child experiences food insecurity.

-

- Family Structure: After controlling for socioeconomic status, children raised by single parents, cohabiting parents, or a step-parent family are more likely to be food insecure than children living with married biological parents.

-

- Child care arrangements: Among low-income preschoolers, attending child care centers is associated with lower odds of food insecurity than being cared for by a relative which in turn is associated with lower odds of food insecurity than being cared for by a non-relative in a home care setting.

-

- Immigrant status: Children of foreign-born mothers were three times as likely to experience very low food security as were children of U.S.-born mothers, even after controlling for other risk factors.

-

- Parental incarceration: Children in households with an incarcerated parent are also more likely to be food insecure due both to the loss of resources while the parent is incarcerated and due to factors correlated with incarceration, such as income levels or community factors.

Food Policies for the 21st Century

Most studies of government food assistance programs, such as SNAP, suggest that participation in these programs lead to substantial reductions in food security. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of SNAP is limited, due to poor take-up rates in some areas and a formula for determining benefit levels that has not been updated in years. In our longer piece for Future of Children, we go into further detail on the role that government policy and programs can play in alleviating food insecurity. There are many open questions about the how food insecurity affects households, but given the high numbers of Americans living in food insecure households, it’s clear that we must continue to examine it critically to help policy makers and program administrators better address this significant policy challenge.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Feeding America’s Children: Food Insecurity and Poverty

September 15, 2014