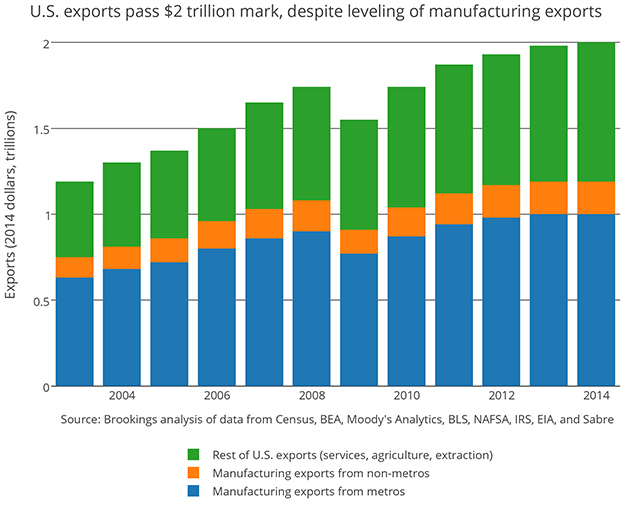

During the long, slow recovery from the Great Recession, international trade has been a bright spot for the U.S., as growing consumer markets in developing countries buoyed firms that faced lackluster domestic demand. Exports accounted for 27% of overall economic growth between 2008 and 2014, and in 2014 they officially passed the $2 trillion mark for the first time.

Despite this progress, exports are taking a lot of the blame for the economy’s disappointing performance more recently. In 2014, U.S. GDP grew by 2.4 percent while exports grew by only 1.8 percent, marking the first year since the recession that export growth trailed overall economic growth. And underlying the disappointing performance of the U.S. economy in the first quarter of 2015 was a 7.2 percent decline in exports. Factors such as a strengthening dollar and notably slower economic growth in Asia and the euro area largely explain the suppressed export growth for U.S. firms.

Updated data released in May 2015 by the Metropolitan Policy Program reveal how these trends are playing out across metropolitan areas, which accounted for 85.5 percent of exports and drove 90.1 percent of export-related growth from 2008 to 2014. Understanding the role and performance of metro areas is critical, not only because they produce the bulk of exported goods and services but also because economic development organizations in metro areas are best positioned to nurture their globally competitive industry specializations and help local firms enter and compete in international markets.

As with the nation as a whole, exports powered metro growth during the recovery before beginning to slip in 2014. Between 2008 and 2014 exports from the largest 100 metros added $195 billion in revenues to the export base, an amount that helped support an additional 638,855 jobs across the country. By 2014, 86 of the largest 100 metro areas had fully recovered and surpassed pre-recession export levels. But in 2014, as imports and domestic trade outpaced exports, the export intensity—or export share of GDP—of the top 100 metro areas slipped from 11.4 percent to 11.3 percent. Last year, only 37 of the 100 largest metros saw exports grow faster than GDP, while 35 metros experienced absolute declines in export volume. Yet declines in highly specialized economies like Salt Lake City and Portland, Ore. this past year appear less significant when set in the context of their above-average long-term export growth rates (11.4 percent and 9.8 percent a year, respectively, since 2003).

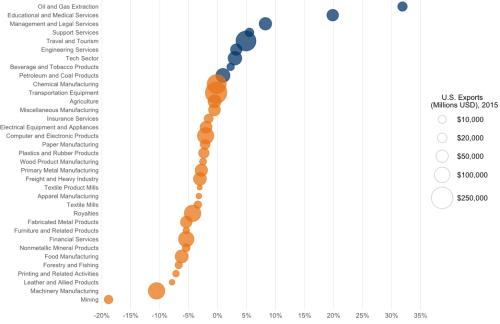

Digging into these trends reveals that most of the export slowdown is due to a dramatic deceleration in manufacturing exports across metros areas (see figure). Lackluster manufacturing demand hit nonferrous metals, motor vehicles and parts, and various machinery products the hardest; together these segments declined over $26.1 billion, or 11.3 percent, in 2014. The majority of the growth that did occur happened in metro areas that export commodities like oil, gas, and agricultural products, which together accounted for 52.1 percent of overall growth, along with sustained international sales from metros specializing in aircraft production, which accounted for an additional 32.6 percent of growth last year.

Substantial regional variations underlie the national export slowdown. Metros in the South and West performed remarkably well, with export growth collectively outpacing U.S. GDP growth. Together, metro exports in the South grew by 2.9 percent and in the West by 3.4 percent, while metros in the Northeast declined by 0.2 percent and in the Midwest by 0.8 percent. Of the 133 metros in which export growth exceeded GDP growth, 105 were in the Southern or Western parts of the U.S. Aerospace-dominant metros such as Seattle and Los Angeles added $7 billion to the West’s export base in 2014, while oil-dominant metros like Houston and Baton Rouge, La. increased export production in the South by $6.5 billion last year. Also among the highest-performing metros were digital technology and research-and-development hubs such as San Diego and San Jose, Calif.

International spending on U.S. products continues to support over 12 million existing jobs in the United States. Export-related revenues support a significant portion of jobs in both manufacturing- and services-oriented metro areas, including 9.2 percent of jobs in Seattle, 8.6 percent in Portland, 8.0 percent in Honolulu, 7.7 percent in San Jose, and 7.1 percent in Wichita, Kan. Export-related jobs pay relatively high wages, and they exist even in often-overlooked export sectors like software, education, finance, and travel and tourism. Underscoring the importance of exports to all sectors of the economy, these service industries are growing as a share of total exports and boast higher job multipliers than many goods industries. For instance, each year metro goods-producing industries support 2.1 direct jobs (and five total jobs) per million dollars of exports, while metro service industries support five direct jobs (and 8.4 total jobs) per million dollars of sales abroad.

Strengthening global headwinds make it all the more imperative that metro areas play an active role in helping their firms access and succeed in international markets. While year-to-year fluctuations in global demand present challenges, exporting can help bolster firms’ competitiveness in ways that go beyond additional revenue. For many firms, exporting is first and foremost a diversification strategy, and it allowed many companies to survive the U.S. recession. A study by Andrew Bernard and J. Bradford Jensen found that exporters were 10 percent more likely to survive over a seven-year period than nonexporters, and the authors called plant survival “arguably the most important potential benefit from exporting.” Exporting also allows firms to spread R&D costs across larger markets, and it can spur innovation by exposing companies to different competitors and new customer demands.

For these reasons, metro areas across the country are proactively investing in their trade-related assets and providing targeted assistance. For some, this means boosting the global profile of the region’s core clusters, like Wichita’s aerospace supply chain, Milwaukee’s water technology firms, or medical device manufacturers in Minneapolis. Others, like Columbus, Ohio, are developing more sophisticated business retention and expansion strategies aimed at identifying high-potential underexporters. Syracuse, N.Y. and Chicago have each hired dedicated regional export leads tasked with identifying these underexporting firms and directing them to metro, state, and federal service providers. Increasingly competitive global markets have spurred some metro areas to double down on their unique connections with global trading partners, whether by country (such as Seattle with China, or San Antonio with Mexico) or by industry (Portland with global metros in need of its green cities expertise, or San Diego with other highly innovative regions such as London and Stockholm). Lastly, in recognition of the significant upfront costs required to enter new export markets, regions are developing programs to minimize barriers to entry. Examples include micro-grants in Louisville and support for market research in Los Angeles.

Leaders in metro areas that are working to build advanced, competitive economies must understand the ways in which local industries and clusters are connected to international markets through exports. This export data provide a starting point for regional strategies aimed at helping firms succeed globally and securing well-paid jobs.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Export Monitor 2015: Growth slows nationwide, but not in South and West

May 13, 2015