This essay opens Chapter 6 of Foresight Africa 2025-2030, which explores how African leaders can leverage their growing presence on the global stage to drive the continent’s priorities.

The renewed global scramble for markets, partnerships, and influence presents a unique opportunity for Africa. How Africa manages these battles will impact its economic growth trajectory and political stability over the next decade.

On the floor of the House of Commons in 1848, Lord Palmerston stated that Britain has “no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.”1 Unlike Britain and the rest of the developed G7, African nations need permanent friends and have permanent interests, but they may need to work on how they moderate partnerships to achieve their objectives in a constantly changing economic and political landscape.

Africa’s economic footprint remains modest on the global stage. With a GDP of about $2.8 trillion in 2024, Africa contributes less than 3% to the world’s GDP and accounts for about 2% of global trade.2 However, politically, Africa’s voice is strong. The continent plays an increasingly pivotal role in global diplomacy, with 54 countries totaling almost 1.5 billion people.3 By 2050, one in four people will be African, with the continent housing the largest number of youths across the globe.4

Africa’s demographic weight gives it a unique and increasingly influential voice in political institutions where one country, one vote is the norm, such as the United Nations. Africa’s voice was clearly heard, for example, when several African nations chose to abstain from a vote on a resolution placing sanctions on Russia at the UN General Assembly. These abstentions have continued on subsequent votes on the matter, showing a growing willingness for African countries to assert their own interests and perspectives on global and continental policy, even when at odds with those of Western powers.5

Africa’s demographic weight gives it a unique and increasingly influential voice in political institutions where one country, one vote is the norm, such as the United Nations.

Against this backdrop, advanced economies have begun to re-evaluate their bilateral collaborations and redefine their partnerships with Africa based on how African countries view issues that matter to them.6 As the continent seeks to increase its voice on the political stage, it must pay even closer attention to shifting political alliances among the G7, G20, and even the BRICS countries. Upcoming changes in leadership in the United States, the political uncertainty in France and Germany, and Italy emerging as a powerhouse in Europe must all be taken into account. Africa must develop policies to manage the changing geopolitical landscape with the singular objective to ensure that partnerships foster sustainable development and empower the African people.

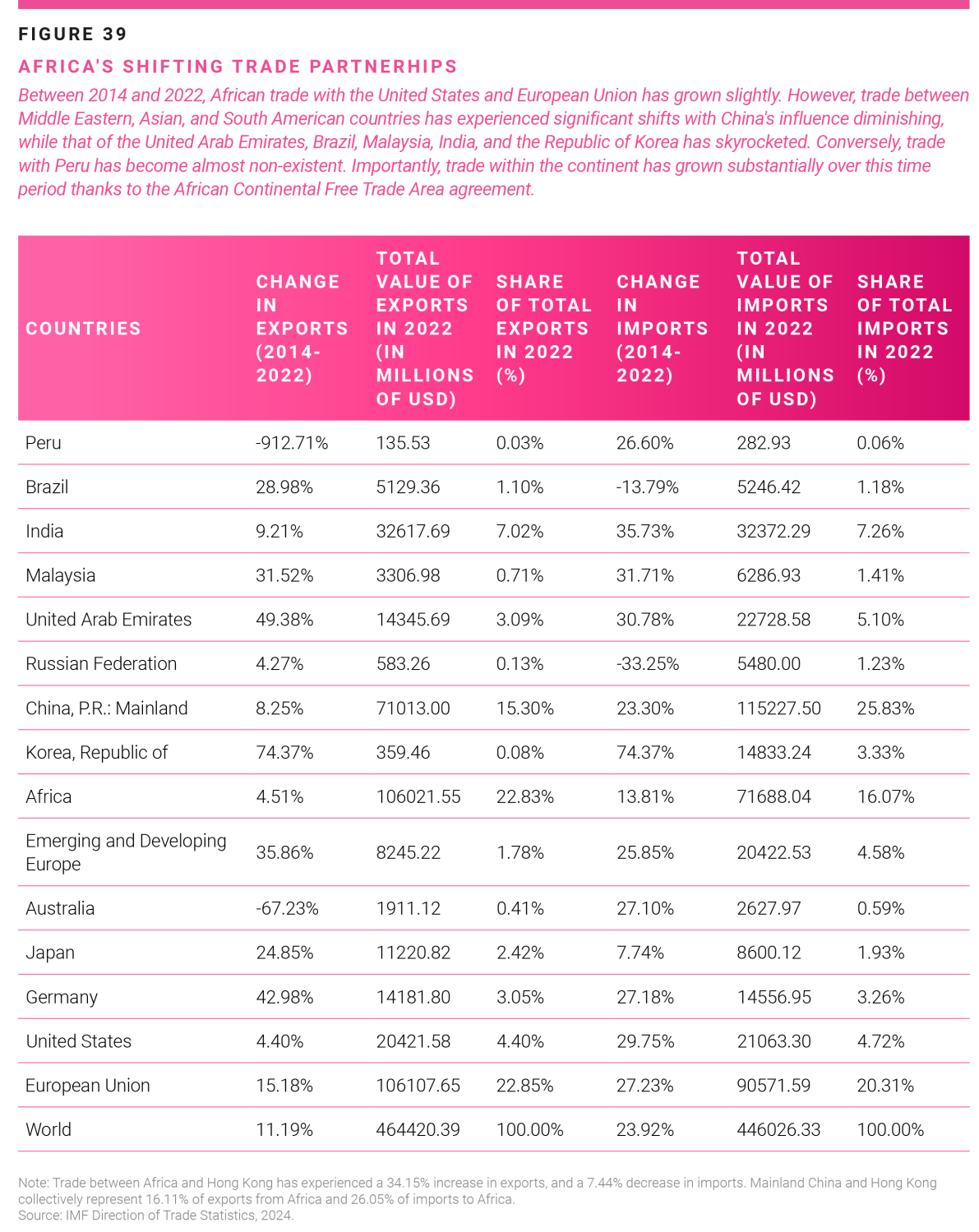

As relationships shift, Africa’s trade partners are diverging from its aid providers. Africa has diversified its trading and financing partners substantially, while it has continued to depend largely on the U.S. and European countries with traditional colonial ties for foreign aid.7 Historically, bilateral partnerships with these Western countries have delivered improved human development gains facilitated by the multilateral development banks (MDBs). In recent years, however, Africa has built new trade partners in emerging economies such as China, Turkey, India, and various Gulf states where the partnerships have focused on infrastructure.8 Middle powers such as these have thus risen in influence on the continent, making substantial investments in mining, military preparedness, and more.9 Europe accounted for only 26.8% of Africa’s merchandise exports between 2014-2023, for example, displaying a sharp decline from the 1990’s, where Europe made up 47.8%. China and India’s share of African merchandise exports has grown from the 1990s—when it was roughly 8%—to 23% in 2023.10

Despite this shift towards non-Western trade relationships, Africa continues to receive substantial aid from its traditional Western partners. Programs like the African Growth and Opportunity Act remain important for many African countries to promote trade with the United States, for example.11 The G7 countries have also remained the largest donors to Africa’s MDB system, as evidenced by the International Development Association (IDA) commitment to send 70% of their contributions to African countries to meet their development needs.12

As Africa seeks to redefine its global partnerships, it must be able to do so without compromising its access to cheaper, long-term, concessional capital from MDBs.

Therefore, Africa is facing a unique tension where trade and aid are now increasingly becoming decoupled. Increasingly, trade partners are demanding political alignment from each other, resulting in friendshoring—the act of moving production and supply chain to allied countries—becoming more commonplace.13 This creates a new partnership dynamic that African nations must negotiate carefully to avoid conflicts between their economic interests and their political ones. This balancing act has become increasingly noticeable on the world stage, as seen with current debt negotiations.14 The G20 common framework is designed to ensure that all creditors have equal share of the debt and that debtor countries participate in the debt restructuring in a comparable manner.15 However, the new common framework built on the traditional Paris Club agreements does not reflect the positions of China and other new donors.16 This has led to delays in the process.17

The key to Africa’s ability to navigate this new landscape lies in regional integration. Africa must continue to leverage its political importance to build more beneficial and stable economic partnerships. Africa can increase its economic attractiveness by deepening regional cooperation to create larger markets and more economies of scale and, ultimately, increase Africa’s share of the global GDP. There are several areas where Africa can take full advantage of global shifts to reposition itself. These include leveraging its comparative advantage in the green economy,18 the shifting demographic trends across regions,19 and the changing influences within the multilateral development system.20

The green economy

Africa has significant potential in untapped carbon markets and renewable energy.21 The climate crisis provides Africa with the opportunity to build new partnerships around economic transformation based on a sustainable net zero investment agenda. By leveraging its natural resources, the continent can create a sustainable economic future while capitalizing on global demand for green technologies and carbon credits. Rich in rare minerals like lithium and cobalt,22 Africa should be a key player in climate policy discussions, enhancing its role in the global green tech industry if it builds the right partnerships. By gaining more control over resource extraction and value chains, Africa can secure better trade terms, ensuring it benefits beyond raw material exports. Africa needs to deepen ties with countries leading in this field such as South Korea, China, and the United States.23

Demographic advantage

With a young, growing population, Africa holds a significant demographic advantage. The increasing youth workforce provides an opportunity for Africa to take control of various markets beyond those related to mineral extraction. Inter-African migration is one way to build comparative advantages across African countries, allowing each region to specialize in economic activities that provide them the best economic outcomes. Several agreements have been put in place to allow the free movement of labor across the continent, including the African Union Passport and Free Movement of People,24 the East African Community Common Market Protocol,25 the Southern Africa Development Community Treaty,26 and the Economic Community of West Africa States Free Movement of Persons Protocol,27 among others. In the long run, migration is a source of economic growth for both the recipient and the exporting countries only when it is managed effectively.28

While many regional agreements regarding migration and the free movement of people have been developed across the continent, Africa has yet to develop an effective migration policy with nations outside of Africa similar to those between Philippines and the Gulf states or India and the United States.29 The shifting global demographic landscape in Africa and Europe, and to some extent in Asia, requires that Africa actively manage the migration debate in a way that provides mutual economic benefits.

Changing global dynamics and influences

There are also many opportunities to embrace new technologies and Artificial Intelligence to accelerate Africa’s integration into the global economy, but only if African nations are able to set up a policy environment for the effective and efficient deployment of these technologies. Today Africa has cost, access, and bandwidth issues which severely handicap the development of these technologies.30 Furthermore, Africa is faced with both political and economic decisions regarding which technologies it adopts. It must also agree on the appropriate regulations to deploy across the continent for data usage, storage, and privacy.31 Once again, learning from the experience of countries like India,32 China,33 South Africa,34 and South Korea35 could present Africa with options that allow it to optimize available technology while continuing to build stable global partnerships and strong economies.

Despite the challenging global polycrisis of the last five years, intra-African trade has remained resilient, growing at a rate of 7.2% year-over-year. This growth accounted for 15% of total African trade, totaling $192 billion in 2023—a miraculous increase from 13.6% in 2022.36 Resilience built during the COVID-19 crisis could serve as a launch pad for faster and more accelerated integration into global supply chains. These trends should be protected and policies developed to leverage them. The ratification by more countries of the African Union Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, Goods, and Enterprises and the Open Skies legislation are important steps in this direction.37

However, as Africa seeks to redefine its global partnerships, it must be able to do so without compromising its access to cheaper, long-term, concessional capital from MDBs. This will require successfully changing the partnership structures of the Bretton Woods institutions. The voting rights systems in these institutions continue to mirror old political alliances and economic realities, with many European countries having an outsized voice compared to those from the Global South. Efforts at the International Monetary Fund and World Bank Group to change the system have been slow and not yet yielded the intended results because of the complex external environment.38

Strategic global partnerships can help Africa meet the key priorities of building up the private sector and accelerating sustainable and inclusive growth. A growing number of regional partnerships provides a promising avenue for African countries to leverage their comparative advantages, creating strong economic growth and development. Traditional intergovernmental organizations and multilateral partnerships must adapt to the needs and maturing influence of Africa for the betterment of the world.

Related viewpoints

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

We extend our gratitude to Nichole Grossman, research analyst at Brookings Africa Growth Initiative, for her outstanding research and editorial support.

-

Footnotes

- “Lord Palmerston,” Oxford Reference, accessed January 2, 2025, https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q-oro-ed4-00008130.

- “GDP, current prices | World Economic Outlook (October 2024),” International Monetary Fund, October 2024; “African Trade Report 2024: Climate Implications of the AfCFTA Implementation” (Cairo: Afreximbank, 2024), https://media.afreximbank.com/afrexim/African-Trade-Report_2024.pdf.

- Saurabh Sinha and Melat Getachew, “As Africa’s Population Crosses 1.5 Billion, The Demographic Window Is Opening; Getting The Dividend Requires More Time And Stronger Effort,” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (blog), July 12, 2024, https://www.uneca.org/stories/%28blog%29-as-africa%E2%80%99s-population-crosses-1.5-billion%2C-the-demographic-window-is-opening-getting.

- Declan Walsh, “How the Youth Boom in Africa Will Change the World,” New York Times, October 28, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/10/28/world/africa/africa-youth-population.html.

- Elias Götz, Jonas Gejl Kaas, and Kevin Patrick Knudsen, “How African States Voted on Russia’s War in Ukraine at the United Nations – and What It Means for the West,” Danish Institute for International Studies (blog), November 15, 2023, https://www.diis.dk/en/research/how-african-states-voted-on-russias-war-in-ukraine-the-united-nations-and-what-it-means; Hannah Ryder and Etsehiwot Kebret, “Why African Countries Had Different Views on the UNGA Ukraine Resolution, and Why This Matters,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (blog), March 15, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/why-african-countries-had-different-views-unga-ukraine-resolution-and-why-matters.

- John J. Chin and Haleigh Bartos, “Rethinking U.S. Africa Policy Amid Changing Geopolitical Realities,” Texas National Security Review, Foreign Policy Africa, 7, no. 2 (May 21, 2024): 114–32, https://doi.org/10.26153/tsw/52237.

- Swetha Ramachandran, “From Empire to Aid Analysing Persistence of Colonial Legacies in Foreign Aid to Africa,” Wider Working Paper (Geneva, Switzerland: UNU Wider, August 2024), https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2024/509-7.

- Chido Munyati, “Africa and the Gulf States: A New Economic Partnership,” World Economic Forum (blog), April 28, 2024, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/04/africa-gcc-gulf-economy-partnership-emerging/; Chido Munyati, “Understanding Evolving China-Africa Economic Relations,” World Economic Forum (blog), June 25, 2024, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/06/why-strong-regional-value-chains-will-be-vital-to-the-next-chapter-of-china-and-africas-economic-relationship/.

- Grace Jones and Nils Olsen, “The New Influencers: A Primer on the Expanding Role of Middle Powers in Africa | The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs,” The Africa Futures Project (Cambridge, Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center, August 5, 2024), https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/new-influencers-middle-powers-africa; Theodore Murphy, “Middle Powers, Big Impact: Africa’s ‘Coup Belt,’ Russia, and the Waning Global Order,” ECFR (blog), September 6, 2023, https://ecfr.eu/article/middle-powers-big-impact-africas-coup-belt-russia-and-the-waning-global-order/.

- “African Trade Report 2024: Climate Implications of the AfCFTA Implementation.”

- Witney Schneidman and Natalie Dicharry, “AGOA Forum 2024: Insights, Economic Benefits for Africa, and the Road Ahead,” Brookings Institution (blog), September 5, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/agoa-forum-2024-insights-economic-benefits-for-africa-and-the-road-ahead/.

- Vera Songwe and Rakan Aboneaaj, “An Ambitious IDA for a Decade of Crisis” (Center for Global Development, 2023), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep58228; “IDA Impact in Africa,” World Bank, accessed January 3, 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/brief/ida-impact.

- Beata Javorcik et al., Geoeconomic Fragmentation: The Economic Risks from a Fractured World Economy (Paris: CEPR Press, 2023), https://cepr.org/publications/books-and-reports/geoeconomic-fragmentation-economic-risks-fractured-world-economy.

- Rafael Romeu, “The Emerging Global Debt Crisis and the Role of International Aid,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 18, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/emerging-global-debt-crisis-and-role-international-aid.

- Kristalina Georgieva and Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, “The G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments Must Be Stepped Up,” IMF (blog), December 2, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2021/12/02/blog120221the-g20-common-framework-for-debt-treatments-must-be-stepped-up; Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, “Sovereign Debt Restructuring Process Is Improving Amid Cooperation and Reform,” IMF (blog), June 26, 2024, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/06/26/sovereign-debt-restructuring-process-is-improving-amid-cooperation-and-reform.

- Abedin et al., “Reforms for a 21st Century Global Financial Architecture: Independent Expert Reflections on the United Nations ‘Our Common Agenda’,” Brookings Institution, April 8, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/reforms-for-a-21st-century-global-financial-architecture/.

- See Kristalina Georgieva and Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, “The G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments Must be Stepped Up,” International Monterary Fund (blog), December 2, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2021/12/02/blog120221the-g20-common-framework-for-debt-treatments-must-be-stepped-up.

- Bruce Bylers, Alfonso Medinilla, and Karim Karaki, “Navigating Green Economy and Development Objectives: Opportunities and Risks for African Countries” (Maastricht: The Centre for Africa-Europe relations, March 2023), https://ecdpm.org/application/files/7116/7930/5470/Navigating-Green-Economy-Development-Objectives-Opportunities-Risks-African-Countries-ECDPM-Discussion-Paper-339-2023.pdf.

- “Shifting Demographics,” United Nations, accessed January 3, 2025, https://www.un.org/en/un75/shifting-demographics.

- Daniel F. Runde and Austin Hardman, “Great Power Competition in the Multilateral System,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, October 23, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/great-power-competition-multilateral-system.

- “Through Its Renewable Energy and Resources Africa Can Export High-Quality Carbon Credits to Generate New Revenue Streams,” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, May 9, 2024, https://www.uneca.org/stories/through-its-renewable-energy-and-resources-africa-can-export-high-quality-carbon-credits-to.

- Gracelin Baskaran, “Could Africa Replace China as the World’s Source of Rare Earth Elements?,” Brookings Institution (blog), 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/could-africa-replace-china-as-the-worlds-source-of-rare-earth-elements/.

- McCartney, “US and South Korea Take Steps to Reduce China’s Grip on Critical Minerals,” Newsweek, November 8, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/america-south-korea-step-reduce-china-news-grip-critical-minerals-1974152.

- “Visa Free Africa,” African Union, accessed January 3, 2025, https://au.int/en/visa-free-africa.

- “Working in East Africa,” East African Community, accessed January 3, 2025, https://www.eac.int/working-in-east-africa.

- “SADC – Free Movement of Persons,” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, accessed January 3, 2025, https://archive.uneca.org/pages/sadc-free-movement-persons.

- “ECOWAS – Free Movement of Persons,” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, accessed January 3, 2025, https://archive.uneca.org/pages/ecowas-free-movement-persons.

- “Leveraging Economic Migration for Development: A Briefing for the World Bank Board” (Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2019), https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/461021574155945177/pdf/Leveraging-Economic-Migration-for-Development-A-Briefing-for-the-World-Bank-Board.pdf.

- For more on the Philippine’s labor export policy, see Jeremaiah Opiniano and Alvin Ang, “The Philippines’ Landmark Labor Export and Development Policy Enters the Next Generation,” Migration Policy Institute, January 3, 2024, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/philippines-migration-next-generation-ofws.

- “Internet Access and Connectivity in Africa,” Diplo Resource (blog), January 18, 2023, https://www.diplomacy.edu/resource/report-stronger-digital-voices-from-africa/internet-access-connectivity-africa/.

- “Africa Technology Policy Tracker,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed January 3, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/features/africa-digital-regulations?lang=en.

- “The United States, Japan, and South Korea Collaborate to Strengthen India’s Digital Infrastructure,” Digital Watch Observatory,” October 29, 2024, https://dig.watch/updates/the-united-states-japan-and-south-korea-collaborate-to-strengthen-indias-digital-infrastructure.

- Rah Pandey, “China Is Dominating the Race for Generative AI Patents,” The Diplomat (blog), December 31, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2025/01/china-is-dominating-the-race-for-generative-ai-patents/.

- “South Africa – Digital Economy,” International Trade Association, September 19, 2024, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/south-africa-digital-economy.

- Chevas Balloun, “Inside South Korea’s Thriving Tech Hub: Startups and Success Stories,” Nucamp (blog), December 24, 2024, https://www.nucamp.co/blog/coding-bootcamp-south-korea-kor-inside-south-koreas-thriving-tech-hub-startups-and-success-stories.

- Isaac Khisa, “Intra-African Trade Values Hit US$192 Billion,” The Independent, June 18, 2024, https://www.independent.co.ug/intra-african-trade-values-hit-us192-billion/.

- “Visa Free Africa”; “Open Skies Agreements,” United States Department of State, accessed January 3, 2025, https://2009-2017.state.gov/e/eb/tra/ata/index.htm.

- Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou, “‘Inequality Starts at the Top’: Voting Reforms in Bretton Woods Institutions,” Atlantic Council (blog), April 12, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/inequality-starts-at-the-top-voting-reforms-in-bretton-woods-institutions/.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).