In late July, amid a tempest in the West Wing, Moscow’s expulsion of hundreds of personnel from U.S. diplomatic facilities in Russia, another North Korean missile launch, and yet more revelations in the Russia-related investigations, now-departed Trump administration official Sebastian Gorka confirmed in an op-ed that the Trump administration intends to issue “soon” its first National Security Strategy (NSS).

The NSS, which has been a Congressionally-mandated requirement since President Ronald Reagan signed the Goldwater-Nichols Act in 1986, offers the president’s appraisal of America’s core interests, challenges, and opportunities, and (to a lesser degree) the means by which the administration intends to achieve its foreign policy vision.

Peter Feaver, Steve Walt, and others have smartly addressed elsewhere the evergreen question of whether the NSS matters. But even the NSS’ true believers must acknowledge that skepticism of Trump’s NSS will—and should—be supercharged.

The credibility of Trump’s NSS will turn on how it reconciles the foreign policy worldviews of its “traditionalists” (National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster, National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn, and most of the national security cabinet) with those of its remaining “nationalists” (National Trade Council Director Peter Navarro, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, and senior advisor and speechwriter Stephen Miller). An NSS enshrining the nationalist agenda is likely to alarm allies and embolden adversaries, while an NSS glossing over the nationalist agenda will be seen as the well-meaning handiwork of the so-called Committee to Save America, but not much more. However the talented team drafting the administration’s NSS manages this tension, if and when Trump publicly “owns” the document, we will still be left wondering whether it is Teleprompter Trump or Rally/Twitter Trump who has spoken.

In the White House’s rosiest scenario, Trump truly embraces the core elements of his NSS—but probably not for long. The impulsiveness that defines his highly personalized style also defies the essence of policy, which generally consists of depersonalized, empirically-informed principles for guiding deliberate decisions and rational outcomes.

And yet, the administration still owes the American people its diagnosis of the United States’ national security challenges and opportunities, and a policy blueprint for addressing both. It owes American service members and civil servants clear guidance on the administration’s priorities. And it owes greater clarity to U.S. friends and allies, for whom existential questions hang in the balance.

In this spirit (but still to be chased with a horse pill of modesty), here are several opportunities and clarifications that the drafters of Trump’s NSS might still seize:

1. Trade (and defining “America First”)

The banner of “America First” has not only energized the president’s base, but also resonated with a broader swath of Americans who believe Washington and its foreign policy have served the global elite—and workers in other nations—better than the American middle and working classes.

The NSS could draw on a trenchant policy narrative about how two decades of foreign and domestic policy have let down the American middle and working classes. This body of work hardly endorses a threatened trade war with China or blowing up the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Nor does it belittle globalization’s role in helping lift more than 1 billion people out of extreme poverty since 1990. But it includes a striking “the order is rigged” argument by political scientists Jeffrey Colgan and Robert Keohane, a pioneering theorist of globalization. It also encompasses the work of economist David Autor and colleagues, whose widely cited series of papers, especially on the “China shock,” have documented the fallout of China’s manufacturing boom and accession to the World Trade Organization, combined with deficient U.S. Trade Adjustment Assistance programs. (This work has also influenced a new wave of scholarship on the relationship between globalization and populism.)

The NSS also might excavate the original arguments made in 2000 to lobby for Congressional approval of permanent normal trade relations with China (e.g., President Bill Clinton arguing that it was “a hundred-to-nothing deal for America” and that “we’ll be able to export products without exporting jobs”). And finally, the NSS could draw on the work of globalization’s thoughtful critics, such as political economist Dani Rodrik, who warned a decade ago of the impossibility of reconciling the “trilemma” of (1) “hyperglobalization”; (2) democratic accountability; and (3) enduring fealty to the nation-state as the primary unit of political order. The real puzzle, Rodrik has argued, is not the recent emergence of populism in advanced economies, but instead “that the world economy could maintain such openness for so long.”

For now, however, “America First” remains a slogan, not a coherent doctrine. Recent actions, such as the initiation of an investigation into Beijing’s treatment of U.S. intellectual property, have demonstrated the administration’s intention to revisit core aspects of the U.S.-China economic relationship. But otherwise, McMaster and Cohn have suggested only that “America First signals the restoration of American leadership … to enhance American security, promote American prosperity, and extend American influence.” Neither this nor other White House taglines calling for “smarter” trade deals have fleshed out a constructive strategy for rectifying Washington’s pursuit of globalization on the cheap.

While the administration has moved to reallocate funding away from federal job training into apprenticeship programs, it seems unwilling to embrace the level of ambition required: an integrated foreign and domestic strategy that not only rebalances elements of U.S. trade policy but also launches significant new investments in the U.S. workforce and social mobility. And while national security hawks often call for rolling back domestic entitlement programs in order to ramp up defense spending, it would be ironic if the Trump administration embraced such a posture in an “America First” NSS. One of the greatest threats to U.S. national security might well be precipitous retrenchment spurred by cuts to the social safety net.

2. Russia

By forcing President Trump to sign a veto-proof Russia sanctions bill, the Congress has bound the administration’s hands on Russia policy, and is unlikely to loosen its grip until Robert Mueller, Justice Department special counsel overseeing the investigation of potential Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, and Congressional committees have concluded their Russia-related investigations.

While the administration remains on probation, the NSS could start down the long road of rebuilding the administration’s credibility on matters related to Russia by enumerating Russian President Vladimir Putin’s sins against the United States, its partners and allies, and the international order. It could begin with:

- Moscow’s active measures to subvert the integrity of democratic elections at home and throughout Europe;

- The continued, blatant violation of the territorial integrity of Ukraine;

- The harassment of U.S. military and diplomatic personnel;

- Unprofessional and dangerous air-to-air and air-to-sea provocations; and

- Hostile developments in military doctrine that put U.S. infrastructure at risk and elevate the potential for nuclearized conflict.

Quoting Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis would help; and the administration must recognize it has no trade space whatsoever on Moscow’s interference in the 2016 U.S. elections. As Feaver has argued, a failure to squarely call out election interference would “be like writing an NSS in the late 1940s and not addressing global communism.”

Second, rather than simply asserting—as Trump has to date—that cozying up to Moscow is a compelling U.S. interest unto itself, the NSS should state clearly how better relations with Russia would serve concrete U.S. national security interests. It should explain how there can be significant improvement in U.S.-Russia relations absent a change in the nature of Putin’s archly adversarial grand strategy, which is focused on undermining the United States’ credibility as a reliable ally, partner, and democracy.

Third, while virtually no one in Washington or European capitals will trust Trump to strike any sort of deal with Russia to enhance European security, such ambition will eventually be needed. Obama’s Russia policy had plenty of critics—including within his administration—who felt that the administration overplayed the prong of its Russia strategy that kept “the door open to working with Russia wherever … our interests might align.” Other analysts have worried that Washington and Moscow are careening toward dangerous escalation. My Brookings colleague Michael O’Hanlon argues in a controversial new paper that the United States and Russia should consider a deal trading a Russian commitment to refrain from violating the sovereignty and territorial integrity of its neighbors for a U.S. commitment to freeze NATO expansion and, with the consent of the states implicated, establish an arc of neutrality including Sweden, Finland, Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Serbia. While I and many others disagree with this proposal, its back-to-basics premise should spark valuable debate toward a long-term strategy for enhancing European security while facing down Russian aggression. The administration’s NSS could soberly frame this strategic challenge even while major moves (rightly) remain on ice.

3. Asia

In his first six months in office, President Trump hosted the leaders of China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam. Vice President Pence has visited Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and Australia. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson also made an Asia swing and hosted the foreign ministers of all 10 ASEAN member countries in Washington. Defense Secretary Mattis’ tour through Asia only 12 days after Trump’s inauguration made a point as the administration’s first foreign trip.

While Trump’s discussions with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi have been a foreign policy bright spot (like those of Presidents Obama and George W. Bush with their Indian counterparts), more than six months in, the White House has yet to offer a major statement of its Asia policy. In fact, the only significant administration statement to date has been Mattis’ apologetic “bear with us” speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June, which promised continuity with Obama’s Asia policy, and promised to “reinforc[e] the international order” and “maintain stability”—commitments that many leaders in Asia have yet to hear from the White House.

In the meantime, China has threatened war with India, the Philippines, and Vietnam—and stepped up demands on countries in Southeast Asia to acquiesce to a Beijing-dominated regional sphere of influence. President Trump seemed to threaten a pre-emptive U.S. strike (“fire and fury”) on Pyongyang if the North Korean regime simply “makes any more threats” to the United States, only to have the national security advisor, secretaries of state and defense, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, CIA director, and even Steve Bannon deny that he really meant it, even as the administration seeks to maintain a clear and credible deterrence posture. Kim Jong Un weighed in three weeks later by testing an apparent hydrogen bomb.

While the administration has talked tough on trade with Beijing, launching broad reviews that could scaffold a range of actions from increasing tariffs on Chinese goods and services to restricting Chinese investment in the United States, the president also has suggested that he may be willing to sacrifice his demands on trade for greater cooperation in pressuring North Korea; Bannon went so far as suggesting that the United States might remove nearly 30,000 U.S. troops from the Korean Peninsula in exchange for merely a nuclear “freeze” from Pyongyang. At the same time, just as solidarity between Washington and Seoul has become more critical than ever for deterring Pyongyang, Trump reportedly instructed his staff to prepare for withdrawing from the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement, without being fully briefed on the potential consequences.

This maelstrom of confusion and contradiction is dialing up the potential for crisis and sowing the seeds of miscalculation. In a best-case scenario, U.S. allies are left scratching their heads, wondering if it is time to consider alternative strategic alignments. South Korean President Moon Jae-in responded to Washington’s threat of a pre-emptive attack on Pyongyang (which would likely trigger hundreds of thousands, if not more, casualties in Seoul) with a remarkable public rebuke. One of Moon’s policy advisors added that, with respect to North Korea policy, “the American government has moved from ‘strategic patience’ to ‘strategic confusion’”—a characterization that, unfortunately, could be applied to the administration’s broader Asia policy.

The NSS presents an opportunity to impose some measure of discipline and priority-setting across the administration’s Asia policy, particularly before the president’s scheduled trip to the region later this year.

A sound strategy would explain how the administration intends to safeguard long-term U.S. security and economic interests—including the security and economic independence of our Asian allies and partners—in the face of Beijing’s increasingly coercive rhetoric and actions. Given the strategic role that the now-scuttled Trans-Pacific Partnership was intended to play by reinforcing the credibility of U.S. staying power in Asia, the NSS also needs to outline the administration’s alternative strategy for securing enduring U.S. interests, beyond plans to modestly bolster the U.S. military presence in the Pacific.

Finally, with respect to North Korea, the NSS can fairly criticize previous administrations for perennially kicking the can down the road. But it also must explain, particularly after Bannon’s comments, how it intends to achieve its stated goal of North Korean denuclearization without precipitating the very events that the U.S. alliance with Seoul is designed to deter: potentially millions of casualties in Seoul (and Japan, too), coupled with the risk of a rapidly escalating war with China.

4. The Middle East

Within weeks of touting a new, unified coalition of Muslim leaders and the transformation of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) into an “Arab NATO,” the Trump administration helped catalyze one of the worst Gulf feuds in decades, driving Qatar into the arms of Iran, and potentially precipitating the end of the GCC.

Since then, the administration has all but confirmed a policy of regime change in Tehran. In June, Secretary Tillerson indicated that the administration was, in addition to “push[ing] back” on Iran’s aspiration of regional hegemony and “contain[ing Iran’s] ability to develop … nuclear weapons,” also “work[ing] towards support of those elements inside of Iran that would lead to a peaceful transition of that government.” Asked to clarify Tillerson’s remarks, National Security Council Spokesperson Michael Anton seemed intent on telegraphing covert support for regime change in Tehran, specifying that “an explicit affirmation of regime change in Iran as a policy is not really on the table.”

The NSS should explain how the administration intends to reconcile, on the one hand, its commitment to rolling back Iran’s regional influence and capacity to threaten U.S. allies and partners, with, on the other hand, its goals of:

- Defeating ISIS in Syria and Iraq, where Iran’s deep ties with anti-ISIS Shiite militias has bolstered Iranian influence;

- Ending the conflict in Syria by deferring to Moscow, which wants military bases in Syria but is otherwise happy for Syrian President Bashar Assad to be a client of Tehran;

- Scuttling the Iran nuclear deal, which has helped contain Iran’s ability to threaten Israel, Europe, and its Gulf neighbors; and

- Avoiding “costly, open-ended commitments.”

5. Technology trends

There is reasonable debate about whether surging anxiety about advances in artificial intelligence (AI) amounts to a neo-Luddism, or, instead, an appropriate, even belated, response to a revolution on the horizon. But no speculation is needed to grasp how automation has already altered the economic and security landscape.

Reports by two of the world’s leading management consulting firms have warned their clients in unusual terms that current technology trends, coupled with stagnant social policy, could undermine the social contract in Western democracies. In a 2017 report on U.S. manufacturing, McKinsey & Company warns that a policy of “inaction … would be a choice to accept the status quo of a two-tiered economy,” and that the “United States is built on free enterprise and individualism, but its growing disparities are antithetical to a healthy democracy.” A 2017 Boston Consulting Group report similarly advises that technology-related “fears of unequal gains and potential job losses” cannot be “answered … with historical analogies purporting to demonstrate that everything will work itself out in the end,” and concludes with a dark warning that “it does not require a degree in modern history to imagine the ends that await us” if economic dislocation and deepening political polarization become “the new normal.”

An NSS published in 2017 must contend with the associated geopolitical implications of these trends—implications that arise from new defense technologies and a potentially shifting military balance; from the capacity of technology to enlarge private power; from transformed labor markets and attendant dislocation; and from the possibility of potentially accelerated economic inequality both within and among nations. Beijing’s recent announcement of a national initiative on artificial intelligence-related technologies, Chinese firms’ access to enormous troves of state-controlled data, and China’s investment spree into technology startups in the United States reinforce this imperative. So does the economic logic of AI, an industry in which, as Kai-Fu Lee, a Chinese technology investor and former head of Google China, has argued, “strength begets strength: the more data you have, the better your product … the more data you can collect … the more talent you can attract…”

While the Trump administration’s Office of Science and Technology Policy has been irresponsibly understaffed, the NSS could, at a minimum, commit the administration to exploiting the expertise of assets positioned at the frontier of private sector innovation (such as the intelligence community’s In-Q-Tel and the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit Experimental) to conduct a net assessment of the security implications of rapid advances in transformative technologies. The NSS could connect such an initiative to the president’s direction this month to the U.S. trade representative to investigate Chinese actions harming American intellectual property rights, innovation, or technology development, and his separate direction to the secretary of defense to lead a wide-ranging assessment of the U.S. defense-industrial base.

All of this should accompany an approach for addressing the security risks of broadly distributed and low-cost genome editing technologies, as well as an overarching cybersecurity strategy that explains how the administration intends to:

- Safeguard the integrity of our democratic elections;

- Double-down on the cybersecurity of the federal government and critical infrastructure;

- Balance the need to respect the private sector’s autonomy and privacy while reducing our aggregate cyber vulnerabilities; and

- Better integrate cyber-related options into our national security planning and crisis response.

6. The moral purpose of American power

Since Harry Truman, every U.S. president has pursued transformation abroad in the service of safeguarding democratic capitalism at home. In so doing, they have sought to marry American power with universal moral purpose.

As the Cold War ended, the Clinton administration sought a world in which “democracy and free markets know no limits.” The George W. Bush administration committed to advancing “human freedom.” And the Obama administration promised to champion “human dignity” while renewing American exceptionalism through “nation-building at home.”

McMaster and Cohn suggested in a July op-ed that the Trump administration might assume a surprisingly maximalist posture: that the administration will “champio[n] the dignity of every person, affir[m] the equality of women” or “protect[t] freedom of speech and of religion…”

This is implausible. President Trump has consistently praised rights-abusing autocrats, and Secretary of State Tillerson has said that promoting our values “creates obstacles” to advancing U.S. security and economic interests. Rights retrenchment has been reinforced by reports that, whereas the State Department’s mission was previously “to shape and sustain a peaceful, prosperous, just, and democratic world,” Tillerson and his senior advisors are considering dropping both the justice and democracy mandates. It is also unclear whether administration officials are aware of, or have quietly rescinded, Presidential Directive 30, which was issued by the Carter administration in 1978 and provides that “it shall be a major objective of U.S. foreign policy to promote the observance of human rights throughout the world.”

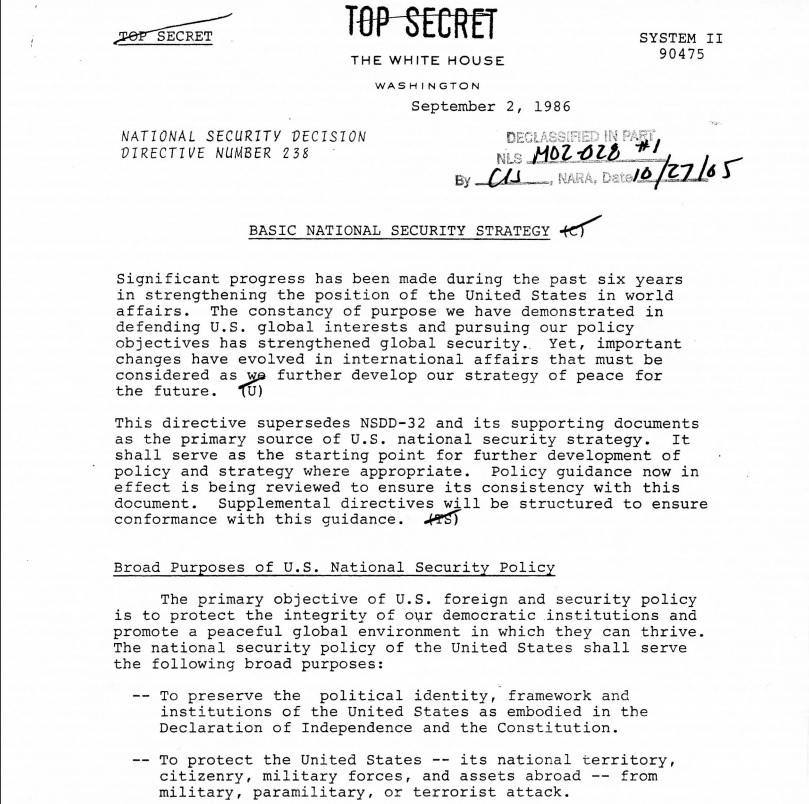

The administration should shelve the misleading rhetoric, and instead explain its theory of how dropping rights promotion abroad safeguards Americans’ way of life at home. The administration must reckon with the decades of U.S. foreign policy it is discarding, from the Truman Doctrine to the Reagan administration’s National Security Decision Directive 238, which argued that Americans’ “way of life, founded upon the dignity and worth of the individual, depends on a stable and pluralistic world order within which freedom and democratic institutions can thrive,” and listed the chief purpose of U.S. national security policy as “preserv[ing] the political identity, framework and institutions of the United States as embodied in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.” (This purpose quite notably came above “protect[ing] the United States—its national territory, citizenry, military forces, and assets abroad—from military, paramilitary, or terrorist attack.”)

Yes, the United States has historically been selective, “directing the rhetoric of freedom at its enemies, not its friends.” President Richard Nixon even suggested that democracy was “not necessarily the best form of government for people in Asia, Africa, and Latin America,” and it was not until the mid-1970s that Washington reconsidered its embrace of convenient authoritarians. But today, Beijing and Moscow see more than hypocrisy in long-standing U.S. policy; they fear support for democracy, human rights, and the rule of law as a potent and threatening tool of American statecraft. Particularly in an era of renewed geopolitical competition, Washington should see it the same way, reinforcing and expanding U.S. partnerships with democratic friends and allies to resist and roll back a coordinated authoritarian offensive against political freedom and democratic accountability.

If not, the Trump NSS should explain the basis for what appears to be—in the absence of any offsetting gains—a policy of unilateral disarmament.

7. Whither the international order

The administration has generated significant confusion regarding its overarching posture toward the liberal international order. McMaster and Cohn’s July op-ed offered a commitment to “bolster common interests, affirm shared values, confront mutual threats and achieve renewed prosperity,” and Trump’s Warsaw speech even nodded to a “community of nations.” But many partners and allies remain puzzled by McMaster and Cohn’s prior assertion in May that “the world is,” in fact, “not a ‘global community’” but merely an “arena where nations, nongovernmental actors and businesses engage and compete for advantage.”

To be sure, an NSS issued in 2017 must highlight intensifying geopolitical competition starring Washington, Beijing, Delhi, and Moscow. But no modern president has won the White House without grasping that ambition should be made of sterner stuff. All have recognized the fundamentally competitive character of international affairs. It was precisely for that reason that they wielded American power to build alliances, partnerships, and institutions that, despite significant flaws, have helped safeguard U.S. interests at home and abroad.

The forthcoming NSS can take credit for spurring some amount of bootstrapping on European defense investment, while reaffirming that the administration means business about burden-sharing in our alliances and multilateral institutions. But it is high time for the administration to tell friends and foes whether Trump intends to build on, or break with, America’s post-war legacy—not least because Moscow and Beijing smell blood in the water.

More broadly, Congress, career government officials, allies, and adversaries have inferred key tenets of the president’s worldview based on his record both pre- and post-election. The NSS will be read to confirm or dispute this inferred wisdom. Silence and ambiguity will be read to vindicate worst fears.

8. Avoiding the blindspots of an “anything but…” policy

Particularly after a change of party, an administration’s first NSS inevitably pledges a sharp break with the foreign policy of its predecessor. Presidents Obama, George W. Bush, and Clinton defined their early foreign policies by contrast with their predecessors, but then managed to articulate more affirmative visions through their respective NSS. Trump’s penchant for ad hominem invective suggests he might struggle with an NSS that does not use Obama’s foreign policy as a guiding foil.

However, a reassuring moment in Trump’s otherwise elliptical remarks on Afghanistan was his concession (or, to some, an admonishment) that “decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office.” A similar acknowledgement in his NSS of structural trends and challenges that transcend presidential administrations would help build credibility with allies, partners, and constructive critics. More fundamentally, such intellectual honesty would provide reassurance that the administration sees core policy challenges clearly, and not through the distorted lens of everything-is-the-fault-of-my-predecessor.

The core North Korea challenge, for example, is not that the Obama administration was unwilling to entertain military options against Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile programs. It is instead that a pre-emptive U.S. military strike could guarantee the deaths of tens of thousands of U.S. troops and potentially millions of innocent civilians in South Korea and Japan.

The key Afghanistan challenge is not—even if one agrees with such stipulations—that the Obama administration lacked a broader regional policy; or that it publicly announced its troop drawdown timelines; or that it imposed overly cumbersome military rules of engagement. Instead, it is the Taliban’s confidence that, whatever the U.S. timeline for a surge of several thousand troops, it can wait out the U.S. commitment to a long-term military presence.

And with respect to Iran, the main obstacle to countering Tehran’s destabilizing actions in the Middle East is not the nuclear deal struck by President Obama. It is instead Iran’s leverage over a host of countervailing U.S. interests in the region, whether in Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan.

Ultimately, the real injury from reflexive scapegoating is not bruised egos or tarnished legacies; it is blinkered reasoning and failed policy.

Conclusion

The Obama administration released its first NSS in May 2010, and the Bush administration issued its first NSS in September 2002. If the Trump administration manages to issue an NSS this year, it will do so significantly earlier than the previous two administrations. But there are reasons why, since the NSS requirement was legislated, no administration has released an NSS in its first year in office. Each needed time to reconcile campaign-driven ambitions with an unforgiving world that even astute advisors “did not fully appreciate when … campaigning.” And early crises intruded on the last two administrations: the Obama and Bush administrations contended with, respectively, the global financial crisis and the 9/11 attacks—foreign policy crises the scale of which the Trump administration has yet to experience.

Ultimately, the NSS has not, and never will, fully capture an administration’s foreign policy. But the odds are long that the forthcoming NSS will furnish even a reliable guide—let alone a reorientation—for the true sources of Trumpian conduct.

As the President is fond of saying, “we’ll see.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).