The COVID-19 epidemic sweeping the globe has affected millions of students, whose school closures have more often than not caught them, their teachers, and families by surprise. For some, it means missing class altogether, while others are trialing online learning—often facing difficulties with online connections, as well as motivational and psychosocial well-being challenges. These problems point to a critical gap in school-based contingency planning within broader education sector preparedness planning and emergency management.

Contingency planning is a management tool to analyze the impact of potential crises and ensure appropriate arrangements are made to respond in a timely and effective way. The tool enables individuals, teams, and organizations to establish working relationships that can make a critical difference during a crisis. As such, education sector and school-based contingency planning for COVID-19 are essential to ensure that schools can manage future uncertainty by developing responses based on different outbreak scenarios, including variations in severity of illness, mode of transmission, and rates of infection in the community. The United Nations Inter-Agency Standing Committee has noted that an effective response at the onset of a crisis is heavily influenced by the level of preparedness and contingency planning.

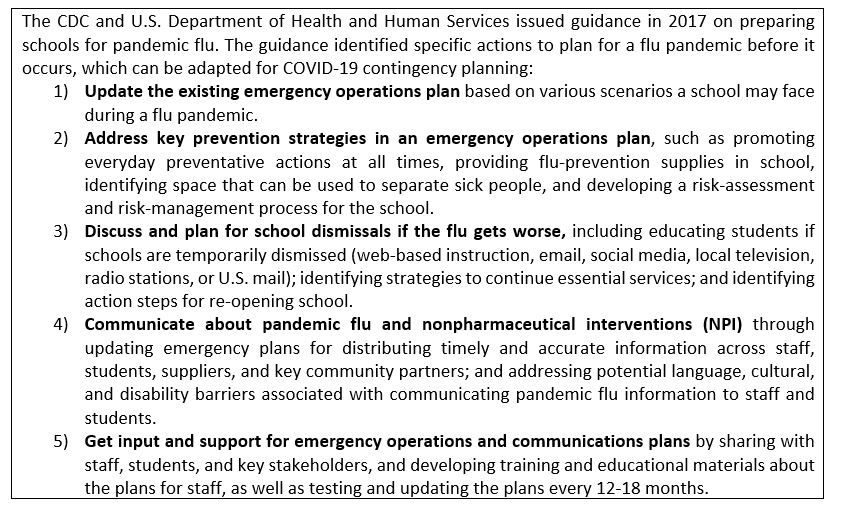

Education sector preparedness aims to protect students and educators, plan for continuity of education, and safeguard education sector investments, all of which ultimately contribute to strengthened resilience through education. The CDC and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services preparedness guidance for school-based pandemic flu notes that school-based outbreaks often give rise to community-wide outbreaks; thus, planning and practicing for such epidemics are an act of safeguarding not only the health of students and staff, but also of the wider community (see guidance below).

Much of the global guidance for schools relating to the current COVID-19 epidemic focuses on keeping schools safe and students and teachers physically healthy through personal and environmental nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). This includes communication about everyday preventative actions like encouraging students and staff to stay home when they are sick, covering coughs and sneezes, washing hands often, and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces and objects. Other schools in communities with isolated cases of the virus are instituting community NPIs, such as increasing space between people at school to at least three feet, making attendance and sick-leave policies more flexible, postponing or canceling large school events, and temporarily dismissing students.

Much of the global guidance for schools relating to the current COVID-19 epidemic focuses on keeping schools safe and students and teachers physically healthy through personal and environmental nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). This includes communication about everyday preventative actions like encouraging students and staff to stay home when they are sick, covering coughs and sneezes, washing hands often, and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces and objects. Other schools in communities with isolated cases of the virus are instituting community NPIs, such as increasing space between people at school to at least three feet, making attendance and sick-leave policies more flexible, postponing or canceling large school events, and temporarily dismissing students.

The CDC guidance notes that in a severe pandemic, “dismissing schools preemptively before flu becomes widespread in schools and communities can help slow the spread of the disease in the community.” While many schools around the world have some sort of preparedness plan in place to deal with natural disasters, armed violence, flu and other emergencies, the vast majority have not planned for the prospect of monthlong or longer school closures, as is happening in China, Japan, and other countries to prevent COVID-19 from spreading. As a result, many schools, teachers, and families lack guidance about how to prepare for educational continuity and psychosocial support to students during long-term out-of-school closures.

Promising actions but critical gaps remain

UNICEF and Save the Children, two leaders in the education emergencies field, have health teams working with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other partners on multirisk preparedness activities across hundreds of country offices to ensure the safety of education programs, children, and affected communities. UNICEF is working with the International Federation of Red Cross and WHO to develop key messages and actions for COVID-19 prevention and control in schools that will serve as the basis for country-level guidance on risk mitigation and safety. This will include specific messages, actions, and checklists for school administrators, teachers, and staff; parents and community members; and students and children. The guidance will also contain a section on engaging students of different ages in health education to prevent and control the spread of COVID-19 and other viruses and to develop media literacy and critical thinking skills to combat social stigma and become active citizens. Save the Children is leading READY, a global consortium aimed at strengthening nongovernmental organizations to support affected governments for major disease outbreaks or pandemics, advocating that children’s best interests are at the center of every response. These actions by UNICEF and Save the Children to protect children and schools through preparedness are important, but neither tackle the preparedness aim of providing educational continuity during school closures.

This lack of research on and guidance for planning educational continuity is disastrous, as education is itself a form of psychosocial support that promotes holistic well-being during crises.

Yet the issue of how to provide quality educational continuity remotely that supports not only learning but also the psychosocial well-being of both students and educators is critical to effective preparedness and response. Countless countries over the past several decades—from Syria and Afghanistan to Somalia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and beyond—have trialed distance and flexible learning approaches to maintain a degree of educational continuity during times of crisis. Unfortunately, the learning from these trials has neither been systematically monitored nor evaluated to measure the impact of these different approaches. Moreover, it is not only the mechanism and approach that is used—from radio, podcast, or television broadcasts to online programs or virtual peer learning circles—but also the quality and methods of teaching that are critical to understand; this opens another set of important, but as of yet, largely unexamined questions about training and support for teachers in already strained educational environments. Until there is evidence on what alternative modes and methods work, and under what circumstances, it will be largely impossible for school districts and individual schools to develop comprehensive strategies needed for education contingency planning.

This lack of research on and guidance for planning educational continuity is disastrous, as education is itself a form of psychosocial support that promotes holistic well-being during crises. Intentional investment in education-based psychosocial support and social and emotional learning for children and youth affected by crises can help them learn more readily. Indeed, psychosocial well-being is a significant precursor to learning and has an important bearing on the future prospects of both individuals and societies.

This COVID-19 epidemic is surely not the last epidemic that will threaten school continuity, especially given research on how climate change will affect infectious disease occurrence. Schools must immediately update their emergency preparedness plans by developing contingency plans that not only address school-based prevention and safety measures for epidemics, but also identify ways to continue educating and supporting students and teachers if schools are closed. At the same time, the global education community must strengthen monitoring, evaluation, and documentation of alternative modes and methods of distance and flexible education work, including how they support the psychosocial well-being of learners and teachers. Ultimately, the global education community should synthesize existing research about distance and flexible education interventions in crisis contexts that can be contextualized at the school-level, so that the next time an epidemic strikes, schools are better prepared to not only protect students and educators, but to continue quality education.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

COVID-19 outbreak highlights critical gaps in school emergency preparedness

March 11, 2020