I recently spoke with Baela Raza Jamil, an education leader from Pakistan, about the complexities of the process of influencing the next global development agenda (commonly known as the post-2015 agenda). Baela is the coordinator of ASER Pakistan, the director of the Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi Centre for Education and Consciousness, and on the Board of the Pakistan Coalition for Education. She shared insights from her recent experience influencing the post-2015 targets for education at the Global Education for All Meeting in Oman.

AA: From May 12-14, you participated in the Global Education for All Meeting (GEM). What was the purpose of this meeting?

BRJ: The goal of the GEM was to provide a global platform for dialogue and coordination on education development goals, including finalizing the education community’s goals, priorities and targets for education within the post-2015 global development agenda. Over 300 delegates from governments, development partners, civil society representatives and experts came together in the labyrinthine corridors of Al Bustan Palace Hotel in the beautiful city of Muscat, Oman. During the three days, which consisted of a ministerial meeting, a senior officials’ meeting and a forum of parallel sessions organized around the themes of increasing equity and inclusion, quality teaching and learning practices, and skills for life and work, the complexity of the post-2015 development agenda setting process was reinforced.

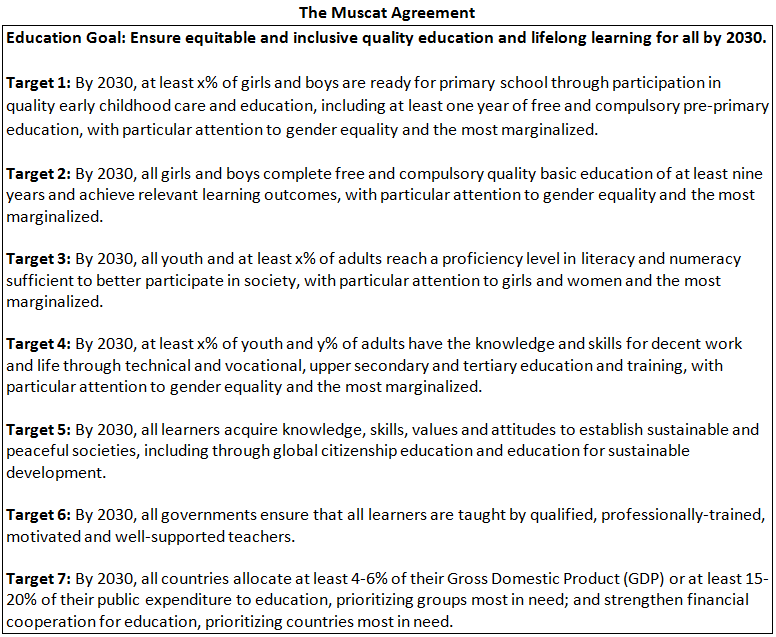

Informed by the previous work of the Education for All Steering Committee and the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals, I worked with old and new partners to influence the seven targets for the stand-alone education goal already proposed by the Education for All Steering Committee for the post-2015 education agenda: “Ensure equitable and inclusive quality education and lifelong learning for all by 2030.”

AA: Can you describe the participatory nature of the discussions and the ways in which you were able to ensure that voices from the global south were heard?

BRJ: It was participatory but with a definite pecking order. There are spaces, stages and association hierarchies to which one has to belong and which require sufficient funding in order to be present at the right place at the right time. Moreover, the post-2015 development agenda process has been dizzying, and its confusing chronology and parallel bodies, lobbies and platforms can leave one confounded. This makes the participation of many civil society leaders, particularly those from the global south who have limited funding and less access to information, more difficult. Thankfully organizations like the Center for Universal Education at Brookings, Save the Children, the Hewlett Foundation, Women Thrive Worldwide, the Global Campaign for Education, Dubai Cares, the Open Society Foundation and others are playing an important intermediary role to ensure the engagement of strategic civil society representatives to inform the process. As such, there was substantive civil society and technical expert input at the meeting; the challenge was that we were vying to influence many strategic areas within a short timeframe.

AA: Can you share a concrete example of how your input influenced the education targets at the GEM?

BRJ: We civil society representatives knew we had to be strategic, so we created a division of labor between colleagues to take positions on and influence the content of the seven targets. For example, myself and colleagues from the Asia-Pacific Regional Network for Early Childhood, Plan International, Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi/South Asia Forum For Education Development and the Pakistan Coalition for Education pushed from the margins to ensure that the target on early childhood care and education went beyond ‘access’ to include quality and the holistic development of young children, especially the most marginalized. The target was originally written as:

- Target 1: Increase the percentage of children who access early childhood care and education (ECCE) to at least x% and start primary education ‘ready to learn’.

We orchestrated our collective voice as a grounded group of practitioners and thinkers, suggesting specific changes and eventually succeeded such that the final target was rewritten as:

- Target 1: By 2030, at least x% of girls and boys are ready for primary school through participation in quality early childhood care and education, including at least one year of free and compulsory pre-primary education, with particular attention to gender equality and the most marginalized.

As a result of this change, young children all around the world—the Nadines, Mamtas, Yasmins and James—may have a greater chance to build strong foundations to survive, thrive and learn with confidence.

AA: Did you run up against any unexpected challenges in influencing the discussion on targets?

BRJ: Yes. There are protocols to the Global Education for All meeting proceedings and procedures that had to be observed, which led to an illusion of participation. For instance, despite the fact that I am a civil society leader from Pakistan and Asia as well as a member of several technical global, regional and national education boards and that I was speaking as a panelist for the GEM session on “Increasing Equity & Inclusion: What Works” organized by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, I was not allowed to give an oral intervention as a civil society expert from the floor of the meeting. I was told that since I am not from one of the formal civil society organizations that had been previously cleared for the drafting committee or the ministerial meetings, I could not speak from the floor during the proceedings.

AA: How did you overcome these challenges in the moment?

BRJ: Myself and other civil society leaders took advantage of the informal opportunities to lobby and network with country delegations, civil society organizations and development partners to ensure support for positions during the formal debates. For instance, civil society coalitions met over lunch on the first day of the meeting and we lobbied to ensure that both the Global Campaign for Education and Education International—which had seats at the formal drafting table—would be carriers of our voice during the three days of deliberations and at the drafting table. We learned who could influence the refinements and additions to the text and agreed to speak with one voice in the formal corridors of influence.

AA: What are the outcomes of the GEM and the next steps for the education community in the context of the post-2015 development agenda?

BRJ: At the closing of the meeting, the UNESCO director-general and Oman’s education minister urged the education community to present the goal and revised targets agreed to in Oman as our common position in the context of the wider post-2015 development process. They emphasized that education, as envisioned by this goal and revised targets, would address environmental protection, gender equality and poverty alleviation by focusing on children, youth and adults and targeting the most marginalized. The Muscat Agreement, as the outcome document from the meeting is called, will be shared with the Open Working Group and U.N. Member States for inclusion in the post-2015 agenda discussions. It will also be adopted at the World Education Forum in Korea in 2015. There is still work to be done, and to influence, as relevant indicators for each global target are now being developed and a Framework of Action for the overarching goal, targets and indicators will be debated throughout the next year and finalized in May 2015 in Korea. Overall, I am hopeful; these targets move from pre-school to primary and beyond and focus not only on access to education but learning and claiming rights; the voices from the margins may become central to human enterprise after all.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Illusion and Reality of Global Participation in Influencing Post-2015 Education Targets

June 5, 2014