The phrase peer pressure is typically linked to risky adolescent behaviors like underage drinking, substance abuse, and unprotected sex. But peer pressure also shapes decisions about education, a recent NBER working paper suggests.

Testing the effect of peer pressure in the classroom

Leonardo Bursztyn of UCLA and Robert Jensen of Wharton used a series of field experiments to test the following question: will 11th grade students be more or less likely to sign up for a free online SAT prep course if their enrollment decision is to be made public later?

Sign-up forms for the prep course were randomly distributed to students in both honors and non-honors classrooms in four low-performing, low-income Los Angeles schools. Each included one of two sets of instructions: 1) enrollment decisions would be kept completely private from everyone including the other students in the room or 2) enrollment decisions would be kept private from everyone except those students. Unable to confer with their classmates or teachers, students simply had to check a box indicating their interest in enrolling in such a course.

A private yes is easier than a public yes

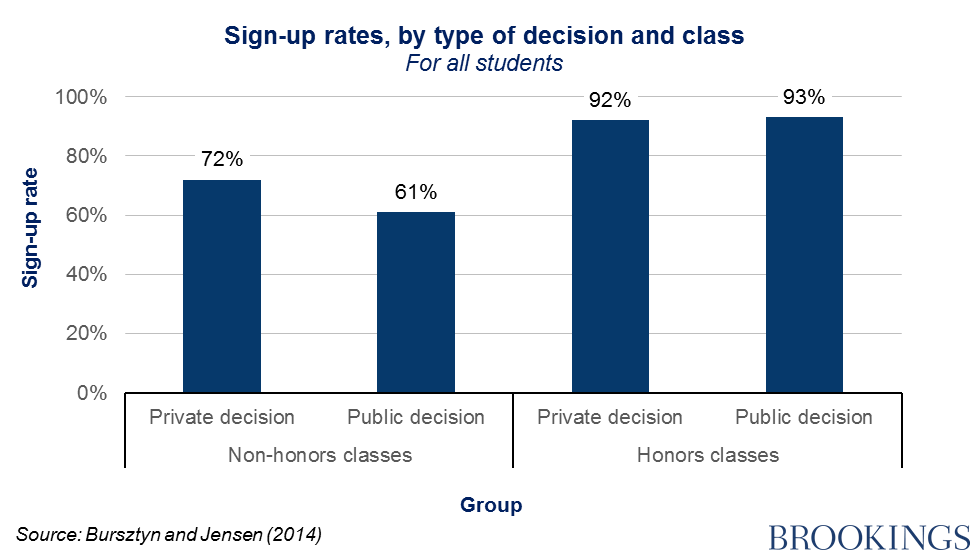

Sign-up rates for the SAT prep course differed significantly based on the type of classroom, with honors students more likely to say yes. But there was also a difference in peer effects. In honors classrooms, students were just as likely to sign up if their decision was made public. Students in non-honors classrooms, however, were 11 percentage points less likely to sign up if they knew their classmates would know:

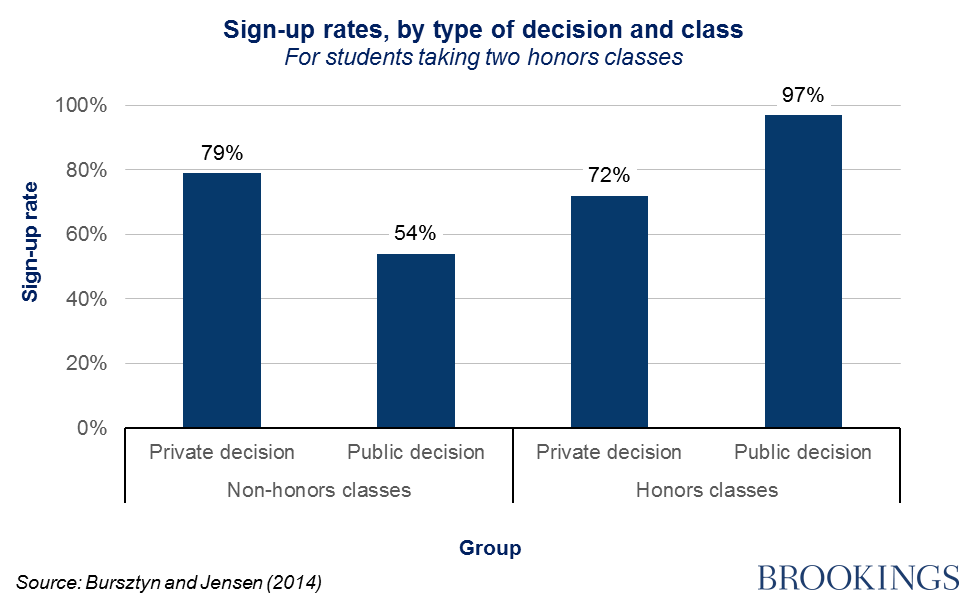

But was it the classrooms or the kind of individual students in those classrooms that explained the difference? To test this question, the researchers looked specifically at “two-honors” students whose course-load included two honors courses out of a possible four or five. Their sampling method ensured that whether these students were sitting in an honors or non-honors class when the sign-up form was distributed was effectively random.

There were even greater differences in sign-up rates between classroom types for these students. In particular, “two-honors” students whose decisions were to made public were about 25 percentage points less likely to sign-up in non-honors classes and 25 percentage points more likely to sign-up in honors classes. This suggest that for these students, peer pressure worked in both types of classroom – but in opposite directions:

Observability matters

To the extent that students feel pressure or fear social backlash from their peers, they adhere to prevailing social norms. This is not to say peer pressure is necessary bad. As this study shows, it depends entirely on the peer group. Marginal students may be pulled in either direction.

Culture, norms and peers matter a great deal for the design and implementation of policy. Policy-makers often assume that giving struggling students additional resources will help them succeed. But this study is a reminder that even providing a valuable service for free may not make much difference if students are reluctant to accept them in a public setting.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Classroom peer pressure: A mixed blessing

March 20, 2015