For decades, churches have been central pillars of community health in predominantly Black communities, compensating for a highly inequitable public health infrastructure. The current COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the important role that churches have played as trusted authorities in Black and Latino communities in disseminating information and in serving as points of access for COVID-19 testing and vaccine rollouts. While positive health and well-being in the communities served by these churches ultimately require significant government investments in public health and health care access points and resources, churches embedded in predominantly Black communities will continue to be important providers of basic health-related services in their communities.

As a result, public health officials will need to become more intentional and systematic in understanding the demographics served by these churches, the ways in which they deliver services, their capacity to serve as potential extension sites for health care access, and the ways in which they support, more generally, the social determinants of health in their communities.

Black churches boost racial equity in COVID-19 prevention outcomes

In an initial attempt to center the public health role of churches located in predominantly Black communities, we focused on two important patterns: the example of the role of Black churches in combatting COVID-19 and whether anecdotal accounts of increases in the closures of churches in predominantly Black communities signal challenges ahead for the delivery of health services in these communities. We wanted to understand, by viewing how Black churches influenced racial equity outcomes during COVID-19, what might be lost when churches in predominantly Black communities close.

In general, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been numerous examples of formal public health organizations partnering with Black churches. Prominent examples include the Mayo Clinic partnership with FAITH! in Minnesota, the collaboration between Liberty Grace Church of God in Baltimore, the International Vaccine Access Center (IVAC) at Johns Hopkins University, the DC Vaccine Exchange Program, and the New York State Vaccine Equity Task Force’s statewide partnership with Black churches.

To be clear, churches have not been the only extension sites of service delivery to reach the Black population. However, communities with high COVID-19 burden and other underlying conditions such as hypertension and inadequate access to nutritious food—a risk factor for hypertension, often have a higher proportion of first-generation immigrants of color, incomes below the federal poverty level, low English proficiency, low or no broadband internet or digital technology use, and high housing instability. Many of the churches in these communities have distributed food through food pantries or soup kitchens and have provided spaces for social interaction long before the pandemic. Because of the models churches often use to address the whole person and other social needs [in contrast to the medical model that focuses on disease]; churches often remain trusted as informal places for health care during the pandemic.

Trends in church closures in predominantly Black communities

We therefore must address what happens when churches located in predominantly Black communities close and their public health functions are disrupted. In order to assess the health impact of those closures, we investigated whether anecdotes about church closures constituted a broader geographic trend.

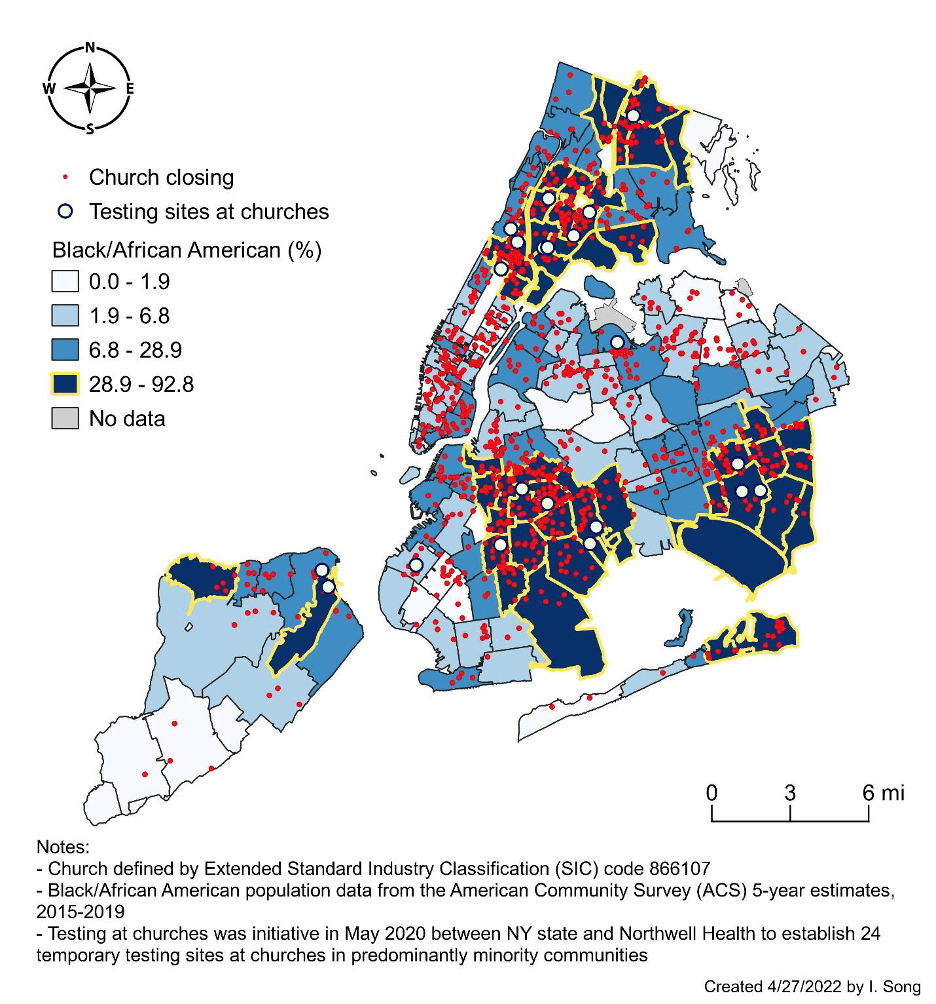

To answer this question, we analyzed church closure patterns in NYC between 2013 and 2019 using the Standard Industry Classification (SIC) code 866107. A church closure is defined as four consecutive years where no data were reported by the church. For instance, “1110000” would indicate data in 2013, 2014, and 2015 but no data in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019 and we would code that “closed.” We mapped these data by the distribution of the Black/African American population using the ACS 2019 5-year estimates, and by COVID-19 positive test rates.

We found that the highest rates of church closures per general population were in the areas with the highest percentage of Black people (Figure 1). Several of these areas (ZIP codes) are where the churches that participated in the NY State COVID-19 testing program were located. To illustrate why churches remain an important extension site for public health collaboration, the maps reveal that a greater rate of church closings were in the areas with the highest COVID-19 positivity test rate (Figure 2).

The conditions under which churches close are many, including changes in the worship attendance, patterns by age and race, possible internal issues, and probably gentrification where market conditions and real estate costs (and predatory development) are forcing churches to vacate or sell the property. The closure of these churches means that marginalized demographic groups (e.g., immigrants, unstably housed, elderly, low income) will have to look elsewhere for health and community services. As a consequence, we must identify the myriad of conditions and determinants of church closures to design policy solutions that address their fundamental role in communities, especially those of color.

Leading the paths towards equity requires faith-based, community, and public health collaborative strategies

The COVID-19 pandemic made clear that existing traditional health care delivery sites are insufficient to meet the needs of large populations, expeditiously. There are too few health centers, many are inadequately staffed to serve high volumes of people, and it is cost-prohibitive to build new ones, staff, and train people in delivering culturally compassionate care. Moreover, several health care delivery sites are inaccessible to racial and ethnic minorities and other marginalized groups such as those who are unstably housed. The reasons for these are plenty, including logistics (e.g., drive time or hours of operation) and socio-structural barriers (e.g., medical mistrust due to discrimination).

To become an equitable nation, and to protect all members of the population, we need public policy that prioritizes collaborations with cultural institutions that are salient to people of color. Churches are central to public health efforts and various stakeholders (e.g., public health officials, racial equity advocacy organizations, congresspersons, real estate developers) should pay attention when there are discernible trends in the disappearance of churches in these communities. Immediate action steps our team began developing include a systematic way for inventorying the health care access and delivery services provided by these churches by characteristics such as denomination and size. Armed with the capability of assessing where needs might emerge if these churches close, stakeholders can engage proactively in decisions about alternate public health accommodations and/or decisions about economic development and urban planning priorities.

Figure 1. The relationship between church closings and Black/African American neighborhood racial composition in New York City (NYC)

Figure 2. The relationship between church closings and COVID-19 positivity in New York City (NYC)

Commentary

Churches are closing in predominantly Black communities – why public health officials should be concerned

May 3, 2022