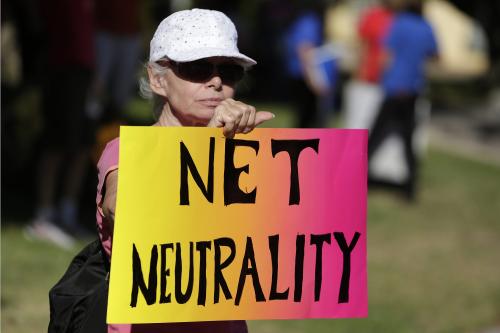

California’s 2018 net neutrality law, SB-822, recently went into effect and concerns have been already raised about the legality of “zero-rating,” the practice by which commercial arrangements and unilateral decisions by network operators are exempted from consumer pricing. Under California’s net neutrality law, zero-rating and sponsored data programs violate the new law because certain content cannot be excluded from consumer data caps, or usage-based pricing.

What set the debate off has been the telehealth app, VA Video Connect, offered by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which allows veterans and their caregivers to meet with VA health care providers via a computer, tablet, or mobile device. Under a 2019 agreement between the VA and wireless carriers, the app is offered free to veterans using their smartphones without counting toward their data caps. But not for long after a leaked email revealed that participating internet service providers (ISPs) and the VA are concerned that their arrangement violates California’s net neutrality law, despite the app’s goal to connect veterans with remote healthcare services. As VA officials reportedly speak with the office of the state’s attorney general, the idea that such application of zero-rating should be admonished is interesting, particularly since this agreement may be in the public interest.

Most consumers are familiar with zero-rating and sponsored data in the mobile marketplace as commercial streaming services, like music and movies, are often exempted from data caps or bundled into unlimited, monthly service packages. For wireless service providers, such offerings allow them to differentiate themselves from other carriers and offset the double charges from application and software providers like Netflix that could be incurred by their consumers.

But the concept of net neutrality codifies that all online content and traffic be treated equally to deter ISPs more generally from slowing down, throttling, or blocking applications online, especially to preference their own products over others. In theory, net neutrality regulation also prohibits zero-rating or sponsored data programs, which can accept assurances or surcharges of content delivery to certain customers.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted net neutrality principles under the March 2015 Open Internet Order, and specifically prohibited surcharges for “better than best efforts,” or paid prioritization to avoid the differential treatment of online content. But the caveat in the 2015 Order was the use of the “general conduct standard” to evaluate potential products and services from ISPs on a case-by-case basis, including tiered pricing and data caps versus exempted usage metering like zero-rating. In 2017, the Trump FCC repealed the 2015 regulation, especially the common carrier provisions, and reinstituted zero-rating and sponsored data programs after the courts deemed that the Order was an overreach of the agency’s authority.

California and other states quickly responded to this repeal by establishing their own net neutrality regimes, including Vermont, Washington, and Oregon. In the 2021 legislative session, nine other states have already introduced similar bills. Some congressional Democrats have also flirted with the idea of quickly reinstating the FCC’s 2015 Order repealed by the Trump FCC, including the reconsideration of Title II common carriage provisions on ISPs.

At face-value, the VA app appears to be in direct violation of California’s law. On the contrary, Stanford law professor Barbara van Schewick argues that the real problem rests on ISPs that should eliminate data caps entirely for consumers or lower the costs of unlimited service plans, which would be allowable under net neutrality provisions. But for the veterans impacted by the potential shut down of the telehealth app, both arguments will require more long-term mitigation (the VA has two years to comply), and possible litigation to be adjudicated. Rather than picking what apps should be permitted for zero-rating, states with current net neutrality regulations, the FCC, and Congress should consider public interest exceptions, even on a case-by-case basis, to zero-rating and sponsored data programs that minimize broadband affordability concerns and offer untethered access to government and government-supported content offerings. The global pandemic has surfaced the widening of the digital divide, economic, and social opportunities when people are not connected to critical government resources. More creative technology options may be able to solve this.

The influence of the pandemic on pressing digital and social needs

In a little over one year, the public health concerns accelerated the digitization of analog activities from shopping to learning remotely. Over 80% of the U.S. population have smartphones or other mobile devices to get online, especially vulnerable populations. People of color, low-income, older, rural, less-abled, and foreign-born populations without home broadband, PCs, or laptops tend to be more “smartphone dependent” when it comes to accessing schools, workplaces, businesses, and government offices, which largely operate from remote platforms since the onset of the pandemic.

More than 40,000,000 people applied for unemployment insurance benefits at the peak of work closures—many via online access. An equal number of K-12 students utilized wireless devices, from smartphones to hotspots, to engage in distance learning. Today, some states are using apps on smartphones and other wireless-enabled devices for vaccine scheduling, among other things. The VA reported that the telehealth app now in jeopardy under California’s law had more than 120,000 veterans access it for care during the high stress on hospitals, which increased their ability to regularly reach roughly 2.6 million veterans from remote locations with limited transportation or hesitancy over in-person, medical visits.

The increasing demand for these social services makes the initial case for zero-rating content that supports the public interest of more vulnerable online users. Unfortunately, California did not have the foresight to understand how their rules may affect certain populations and the applications serving them, which is why some exceptions should be made for zero-rating applications and programs oriented for the public good.

Zero-rating and the federal Lifeline program

Before going into what modifications can be made to California’s net neutrality law, there is another opportunity regarding the use of zero-rating and other sponsored data programs to support vulnerable populations. The federal Lifeline program, which is administered by the FCC through the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), provides a discount up to $9.25 for eligible consumers on communications services—either phone or broadband. The program’s benefit, which was established under President Reagan in 1985, has remained somewhat stagnant since its inception, despite the transitions from telephony to wireless to broadband services. Proposals have been shared with the current FCC on how to modernize the program with more competitive offerings and funding, increased consumer control on how they use the benefit, and expansion to government agencies focused on human and social services.

The proof-of-concept of the VA’s arrangement with wireless carriers suggests that zero-rating or government’s sponsorship of critical content not only lowers the monthly costs of data, but also incentivizes its use. Complementing and expanding the current Lifeline program with zero-rated access to government content can support eligible subscribers’ abilities to:

- Find federally assisted housing through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Enroll and complete required workforce training or credentialing via state and federal workforce sites.

- Apply for public benefits online and monitor their health outcomes post-pandemic via the Department of Health and Human Services and local health departments.

- Access early learning and child development services available by the Department of Education.

The automatic exemption of dot.gov domains from data caps in these and other use cases would entail agreements like the one with the VA where federal agencies could work with ISPs to subsidize the free data or establish a financial arrangement between USAC and ISPs to cover the costs. The latter arrangement could compel higher rates of participation in the existing Lifeline program, especially among participants receiving government benefits. Sponsored data programs between government agencies, ISPs, and other providers, could also introduce related public interest-oriented content offerings through partnerships with online job search engines or hospitals offering remote patient monitoring to medically underserved patients, where free data improves communications and engagement. While these and other programs could happen now under the current FCC, they would be prohibited in California, and at risk if stringent net neutrality regulations were to be re-established nationally, which prompts the following recommendations for state and federal leaders.

1. California could amend its net neutrality law to include a case-by-case review of zero-rating and sponsored data programs.

The pandemic has demonstrated just how important connectivity is, particularly for vulnerable populations. Consequently, any existing and future rules of the road for the internet should accommodate the organic coupling of innovation and the delivery of government services. As the transition from analog to digital experiences accelerate, broad concerns on how to close widening digital and economic gaps will persist, and online rules should be flexibly applied to acknowledge their evolution. For example, the time between the adoption of the California order and its ultimate implementation appears to have missed mounting consumer vulnerabilities (both online and offline) and new opportunities where technology can be leveraged to improve quality of life or life chances, like facilitating veterans’ access to telehealth services. California could address this and future discrepancies inherent in their law by adopting a case-by-case review of zero rated and other sponsored data programs, much like what was written into the FCC’s 2015 Order. Exceptions for prioritization could be permissible after it is cleared from being anti-competitive and in support of the public interest. Furthering the use of the general conduct standard in California could also facilitate immediate and meaningful exceptions to their net neutrality laws, which could be of interest to the FCC or Congress if debates around open internet principles are reopened.

2. The zero-rating of government and other government-supported content should be immediately applied to the FCC’s Lifeline program.

Eligible consumers should have unlimited access to all dot.gov domains, especially those that promote access to government or other public sector content, like scheduling vaccine appointments with the health department, filing for social service and unemployment benefits, identifying workforce training and opportunities, locating educational supports, among other functions that can be performed on mobile devices. Participating Lifeline ISPs should make these activities readily available to their customers without penalty to their data usage and perhaps all subscribers in due time through formal agreements with federal agencies directly or USAC. The exemption of such content for vulnerable populations, including veterans, not only incentivizes cost-prohibitive consumers to engage, but also starts the process of modernizing how government services are offered over mobile and other digital platforms.

3. Congress should establish a federal standard on net neutrality once and for all to bring certainty to the marketplace for the private and public sectors.

What is happening in California is the anticipated outcome of a patchwork of state-specific, internet regulations. Congress, private companies, government, and civil society organizations largely have some consensus around the principles of an open internet. While getting agreement on how to operationalize them may be more intense, any new stab at net neutrality regulation must be adaptable to how technology is evolving and realize that the plethora of online options are increasing both the supply and demand for broadband services. Net neutrality is one of many legislative solutions to address national broadband access and use. Policymakers must also focus similar energies on the review and modernization of the current universal service program and confront the pernicious outcomes that result from an absent federal privacy standard in the U.S., like deceptive online advertising, individual and societal biases emanating from artificial intelligence systems, and misinformation.

It is still too soon to know the fate of the VA’s app. But there is some time to explore broader and more flexible approaches to internet regulation that allow for innovative and creative public interest content to directly cater to the needs of the nation’s most vulnerable populations.

Commentary

California’s net neutrality law and the case for zero-rating government services

April 19, 2021