Presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg is, at heart, a liberal internationalist who is looking beyond interventions to challenges posed by great powers, bridging the gap between the Obama and Clinton wings of his party, argues Thomas Wright. This piece originally appeared in The Atlantic, where Wright is a regular contributor on the foreign policy debate for 2020.

Pete Buttigieg’s foreign-policy speech started with a thinly veiled jab at President Barack Obama and his vice president, Joe Biden. For “the better part of my lifetime,” Buttigieg said, “it has been difficult to identify a consistent foreign policy in the Democratic Party.”

“We need a strategy. Not just to deal with individual threats, rivalries, and opportunities, but to manage global trends,” he said. And he warned that “Democrats can no more turn the clock back to the 1990s than Republicans can return us to the 1950s, and we should not try.” In case anyone had missed the point, he added, “Much was already broken when this president arrived.” Buttigieg offered plenty of criticism of President Donald Trump, of course, but his message was clear: I will be different from my Democratic predecessors.

But in the hour that followed, Buttigieg sounded very Obamaesque. He even began with an introduction by Lee Hamilton, whom Obama admired and embraced in 2007. Buttigieg was thoughtful in how to deal with individual threats and challenges, including climate change and right-wing terrorism, but did not offer an overarching strategic vision. He was passionate about modernizing the American system at home to prepare for the future. He spoke of living our values at home, just as Obama and Biden do. He struck a middle ground on intervention, calling for an end to the wars of 9/11 but outlining criteria that would allow for future interventions, even unilateral, if the stakes are high enough and other options have been exhausted. He made time for technocratic fixes to the national-security bureaucracy. He praised allies in general but mentioned none by name, except those with whom he had a problem. Obamaesque indeed.

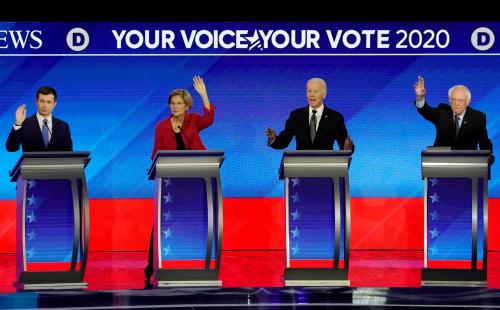

By contrast, whether you agree with them or not, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have been crystal clear in what they see wrong in the Obama years. They believe the former president tolerated a rigged global economy, did not pay enough attention to oligarchic authoritarianism, and set the defense budget far too high. There is a centrist critique too: Obama was too complacent about the trajectory of world politics, did not take geopolitical competition seriously enough, and proved too risk-averse. Buttigieg seemed to want to have it both ways—to be the candidate of change within his party without ever quite explaining what that meant.

The closest he came was on China—the most impressive part of his speech, along with the passage on climate change—admirably warning of the rise of techno-authoritarianism and condemning reeducation camps in Xinjiang. Buttigieg seems genuinely offended and worried by China’s challenge to liberal values. He told The Atlantic’s George Packer that China seeks “the perfection of dictatorship,” that “it’s not wrong to perceive a real challenge from China,” and that the Trump administration’s orientation on China is not completely incorrect. In other recent interviews, he has spoken about the China challenge, and he tweeted about the anniversary of Tiananmen and Hong Kong, so this has been building for a while.

But even on China, there were missed opportunities. He did not say, as former Obama-administration officials have written, that successive administrations have gotten China wrong in important ways—this would have allowed him to make the case for a break with Obama. Although he implied as much, he stopped short of explicitly stating that the United States is in a geopolitical competition. He said nothing about his affirmative vision for the Asia-Pacific, the key geopolitical element of any China policy. He spoke about improving domestic competitiveness, but Warren has gone further in calling for an industrial policy to invest in key technologies where the Chinese mercantilist system may have an edge. The China frame has a lot of potential as a political message, but Buttigieg will need to do more to explicitly link his foreign policy to his economic agenda.

International economics may be where Buttigieg is most vulnerable. He promised to take the concerns of the middle class into account. However, he also said that “globalization is not going away,” and that the way to deal with its challenges is to harness the potential of global markets, support immigration, and leverage the education system.

It was all a bit mid-2000s. There was no suggestion that the United States and like-minded countries could change the patterns of globalization if they so desired. Trade was mentioned only in passing. We were left none the wiser as to whether Buttigieg supported the Trans-Pacific Partnership or the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership or the World Trade Organization. He did call for updating international institutions, but that was a line that could have been—and indeed was—uttered by Obama in 2007. Then it was fresh. Now, without details and with adverse shifts in Brazil, China, and Russia, it sounds clichéd.

Unless he changes course quickly, Buttigieg has created a real opening for the other candidates to go after him on globalization. Even if he manages to parry those attacks, he missed an opportunity. There is a middle ground between the old consensus of the 2000s and Warren and Sanders’s argument that globalization is essentially a conspiracy perpetuated on the American people by corporations and vested interests. Some economists, such as Larry Summers, now advocate for a policy of “responsible nationalism,” pressing for more stringent regulation and making sure companies don’t use international tax law to their advantage. There’s innovative thinking among Democrats on how to work around a flawed WTO and build an international coalition to address Chinese mercantilism, but Buttigieg did not offer it to his audience.

One topic Buttigieg did distinguish himself on was military intervention, and there he might have laid a trap of his own for his more progressive rivals. Intervention is not very popular among Democrats at the moment. Sanders and Warren have railed against it, but haven’t outlined any criteria for when they would intervene. Buttigieg did. He said that vital interests would have to be at stake and that force must be a last resort. Unilateral intervention would be justified only in exceptional circumstances. He embraced the doctrine of Responsibility to Protect, which provides for intervention to stop genocide.

Progressives will be tempted to criticize him, but he can fairly ask what their criteria are: Do they propose never to intervene, even if confronted with an imminent human-rights atrocity with congressional support and a viable military plan? However, he may have undermined his own message in his interview with Packer when he said he would have opposed limited military strikes on Syria in 2013 because the U.S. lacked allied and congressional support. (In fact, American allies generally backed U.S. strikes.) He said he would never have drawn the red line in the first place—which prompts the question of whether he would tolerate the use of chemical weapons without punishment.

Buttigieg took a firm line against Israeli annexation of the West Bank, suggesting he understands the role of power and leverage in American foreign policy. However, his pledge to simply rejoin the Iran nuclear deal as if nothing had happened smacked of naïveté—repairing the damage Trump has wrought will be a much more complex and difficult task.

Buttigieg also struck a different note than progressives typically sound on the defense budget. He asked the right question—does America have the right type of military?—rather than calling for unilateral cuts. He made a powerful case for modernization to deal with future threats. He made important points on disseminating the truth in an age of deep fakes and state-sponsored disinformation. Yet he was weak on geopolitics. His discussion of Asia was confined entirely to China and North Korea, and his discussion of Europe was entirely about Russia. He had nothing to say about the major trends in East Asia or Europe, although he did speak more about Africa.

Reading between the lines of his speech and recent interviews, there might be a way to understand Buttigieg’s policies that he himself is not yet willing to articulate. He is an heir to Obama’s cautious and intellectual worldview—except that while Obama was, at heart, a realist influenced by the writings of Reinhold Niebuhr and the actions of Brent Scowcroft, Buttigieg is more motivated by values. Buttigieg is, at heart, a liberal internationalist who is looking beyond interventions to challenges posed by great powers, bridging the gap between the Obama and Clinton wings of his party. He fears that, left untended, threats to liberty abroad will ultimately threaten liberty at home. Buttigieg still has a lot of work to do to unpack what this means, but if he sticks to it and is bolder than he was on Tuesday, he may be able to articulate the alternative he promised.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Buttigieg splits from the progressives on foreign policy

June 13, 2019