As we head into 2024, experts from the Brown Center on Education Policy identify the education stories that they’ll be following in the new year, providing analysis on how these issues could shape the learning landscape for the next 12 months—and possibly well into the future.

Douglas N. Harris

Last year, I wrote that I wasn’t expecting to see many signs of rebound from COVID-19 learning loss but that I was hoping to see signs of permanent improvements in schools, perhaps prompted by the pandemic. While economists (including me) aren’t known for accurate predictions, these two seemed to be on the mark. Learning loss persists. But tutoring is expanding and probably improving. I had also mentioned the possibility of banning cell phones in schools, which students relied on heavily during the pandemic, and we did see more media stories about that option. I hope we keep pressing ahead on school improvement in 2024.

I’ll be looking for more stories about universal school vouchers and educations savings accounts (ESAs). (I call these “super-vouchers” because they are available to all families and the funds can be used not only for private school tuition but also expenses associated with homeschooling.) Eight states now have these super-vouchers and more seem to be on the way. I think we will—or at least should—start to see more national conversation and evidence about them. Based on prior evidence of the most similar programs, this does not bode well for the usual academic metrics (especially test scores). Depending on how many states follow suit, I think this could end up being the biggest policy change in K-12 education since Brown v. Board of Education—and likely to reverse Brown’s influence in several ways.

Michael Hansen

Discussions of burnout, high attrition, and shortages have dominated news stories about the K-12 teacher workforce since the pandemic emerged. This will abruptly shift in 2024 as the ESSER recovery funds expire and districts face a fiscal cliff. Despite warnings to avoid using recovery dollars to beef up staffing levels, many districts have done exactly that. Teacher staffing has largely recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and with declines in student enrollment since the pandemic, teacher-student ratios are now slightly higher than 2019 levels.

Not all school districts face the same budget shortfalls. Contractions will be tightest in districts that initially received the most support (primarily those serving high concentrations of high-need students) that have since disproportionately lost student enrollment. Many of these schools were closed for prolonged periods during the pandemic and experienced large setbacks. In other words, districts with students lagging the farthest behind will be most at risk from a shrinking workforce. To minimize damage from these cuts, districts should equally share the burden of teacher reductions across all schools and prioritize the protection of qualified and effective teachers (not simply layoff the most recently hired). Further, defining teacher race as one of many factors representing teacher quality can preserve recent gains in workforce diversity.

This could be a rollercoaster year or two for the teacher workforce. However, with some strategic prioritization of workforce goals across different settings, districts can emerge leaner and more effective.

Katharine Meyer

In 2024, I’m hoping to see a concerted effort at meaningful reform to the higher education system. While the Biden administration’s attempts at widespread student loan debt relief are ongoing, those efforts must be paired with changes to the underlying system of financing postsecondary education. It’s time for critical conversations about the effectiveness of different loan programs at expanding access to education for the most in-need students and whether expanding and targeting grant aid would better achieve those outcomes.

Similarly, for decades, colleges used race-based affirmative action to diversify their student body because that diversity was not achievable under the status quo admissions process. Without that tool, it’s time for colleges to reflect on their missions, how their admissions policies align with those missions, and what they must do—during initial recruitment, application review, and conversations with admitted students—to achieve those missions.

Finally, I expect to see a focus on accountability. Federal accountability efforts this year included reinstating gainful employment rules and developing low-financial-value metrics, and next year will kick off with a new negotiated rulemaking committee around accreditation and distance learning. But the federal government is only one part of the “regulatory triad” that provides oversight on higher education institutions; state governments and accreditation agencies represent the other two prongs of oversight. Next year, I expect an increased focus on how these other actors could improve their oversight efforts.

Rachel M. Perera

In 2024, I will be watching how the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) resolves a number of high-profile civil rights investigations that have been opened in the last two years. This includes several investigations into concerns of antisemitism, as well as anti-Muslim and anti-Arab discrimination on K-12 and college campuses. I’ll also be watching how OCR resolves open federal probes related to concerns of illegal discrimination against racially minoritized and LGBTQ+ students, as well as students with disabilities in Carroll Independent School District in Texas (the district featured on the popular NBC News podcast Southlake). While some believe that OCR’s involvement will force institutions to take action against discrimination, OCR investigations are typically lengthy (ranging from six months to several years) and whether their involvement successfully remedies discrimination remains an open question.

Finally, I’ll be following the legal battle over new admissions standards recently adopted at Thomas Jefferson High School, an elite magnet school in Fairfax County, Virginia. In question is whether a school district can adopt a facially race-neutral policy to increase racial and socioeconomic diversity. The Court has long promoted the use of race-neutral policies to achieve a diverse student body, and a reversal would represent a major upheaval for many K-12 education systems. The case is currently being appealed to the Supreme Court after an appeals court ruled that the new admissions policy was not discriminatory.

Jon Valant

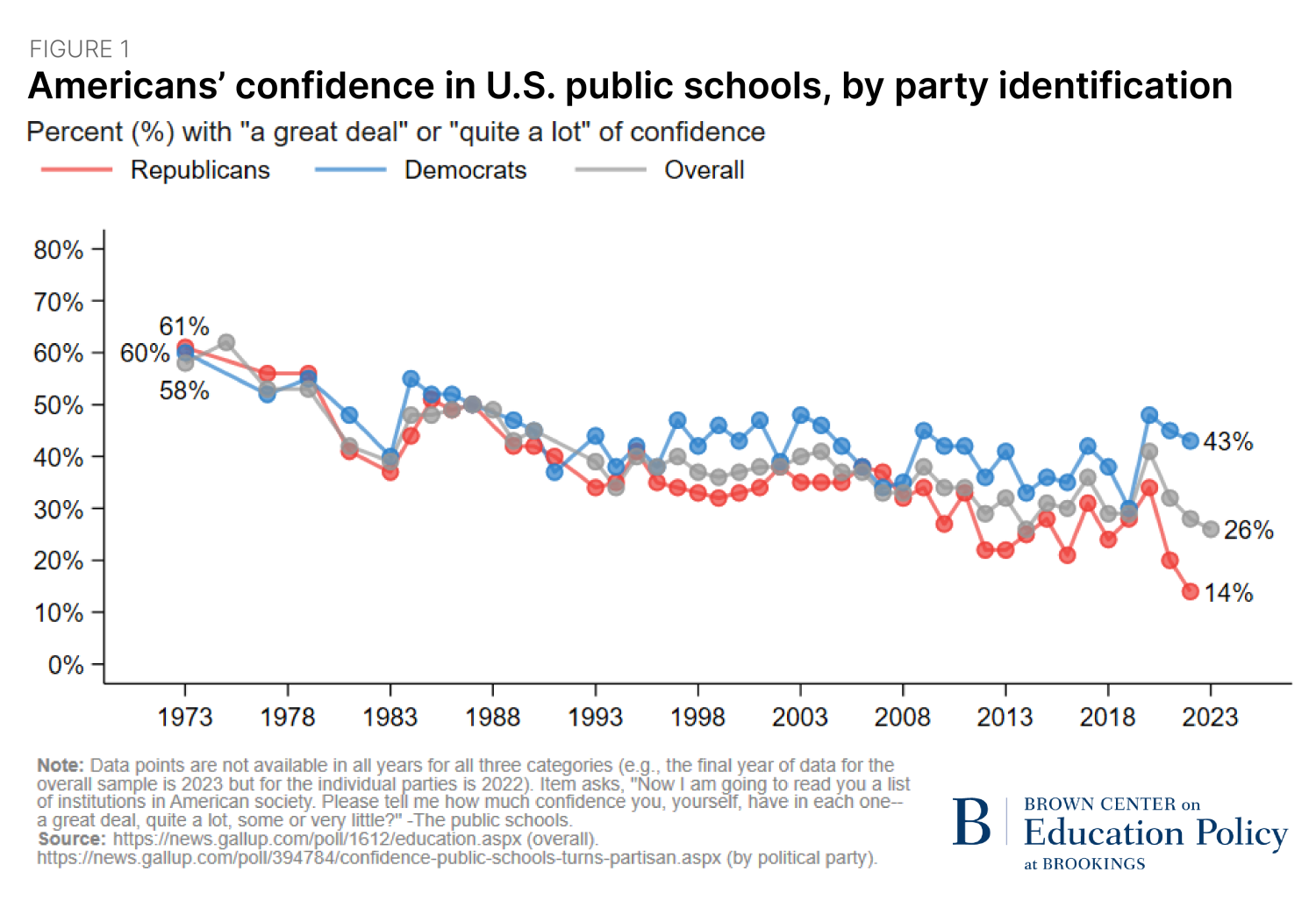

I expect to be watching polls in 2024—and not just the ones that we’ll all be watching. There are worrisome trends in what Americans are saying about U.S. public schools. Of particular concern is Republicans’ waning regard for public schools, as well as the historically large gap between the views of Democrats and Republicans. Figure 1, below, shows a half-century of Gallup polling data. (One important note: Americans tend to feel better about their local public schools than U.S. public schools as a whole.)

How much of this is lingering, but hopefully short-lived, frustration over schools’ response to COVID-19? How much is deeper-seated disregard? We’ll find out soon enough. Disregard for public schools could fuel the expansion of universal ESA programs that are beginning to account for sizable shares of some states’ education funding. It also could produce cultural shifts that affect decisions made by policymakers, voters, parents, students, and educators (or would-be educators).

K-12 issues will arise in the 2024 races, though I don’t expect them to be prominent in the presidential race. And with an uncontested Democratic presidential primary, we are unlikely—unfortunately—to get much of a party-wide conversation about Democrats’ vision for K-12 education policy.

Kenneth K. Wong

Public charter schools are facing new challenges in 2024, even though the charter sector seems robust as it enters 2024. Student enrollment in charter schools doubled between fall 2010 and fall 2021. About half of Washington, D.C.’s school-age children attend charter schools, while charter schools in several states enroll more than one in ten of their states’ public school students. Charter parents were generally satisfied with schooling support for the learning and mental needs of their children during the pandemic. Recent studies also found that urban charter schools have outperformed their district peers. Despite favorable parental sentiments and relatively solid academic performance, charter schools face challenges in 2024. First, leaders in districts with declining population are trying to stabilize district enrollment, including potentially restricting charter school enrollment. Second, school districts have to address the “fiscal cliff” as supplemental ESSER funding begins to phase out. Stabilizing district head count will buffer the impact of fiscal retrenchment. Third, charter schools are likely raised as state and local governance issues in an election year. How these factors will shape charter school growth in districts across the nation will be an issue to watch in 2024.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Brown Center scholars look ahead to education in 2024

December 19, 2023