Brookings is adopting a long-overdue policy to properly recognize the identity of Black Americans and other people of ethnic and indigenous descent in our research and writings.

This update comes just as the 1619 Project is re-educating Americans about the foundational role that Black laborers played in making American capitalism and prosperity possible. Without Black might, there would be no white wealth. Yet for over three centuries since the first colonists landed on American soil, Black people were considered less than equal under the law.

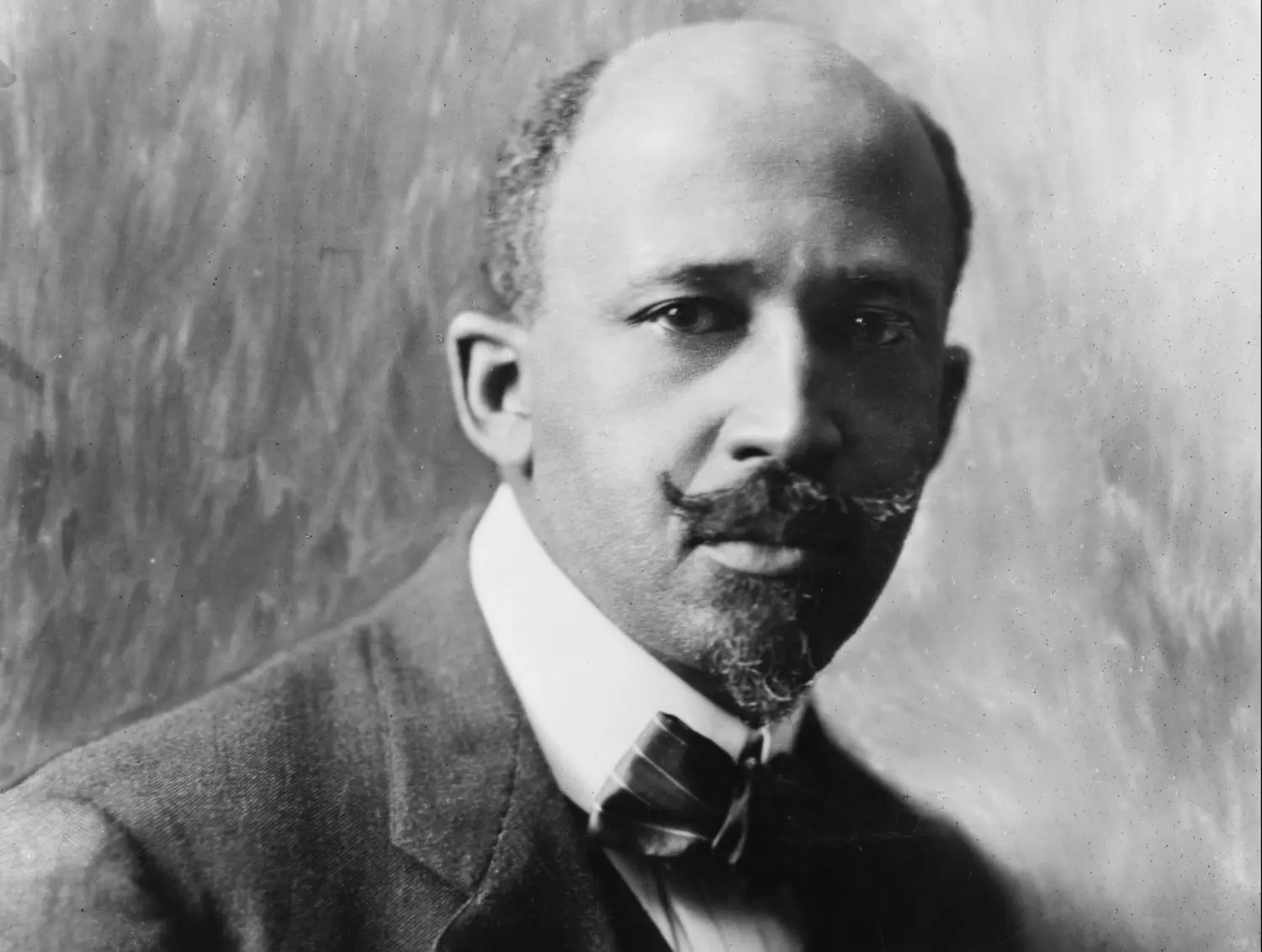

In fact, after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, the federal government struggled to determine what to call freed Black people. The government used various labels: black, negro, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon. It wasn’t until 1930 that the U.S. Census Bureau finally settled on one prevailing term: “negro.” Years earlier, W. E. B. Du Bois, activist and co-founder of the relatively new NAACP, had launched a letter-writing campaign to major media outlets demanding that their use of the word “negro” be capitalized, as he found “the use of a small letter for the name of twelve million Americans and two hundred million human beings a personal insult.” After initially denying the request, the New York Times would update its style book in March 1930, noting, “In our Style Book, Negro is now added to the list of words to be capitalized. It is not merely a typographical change, it is an act in recognition of racial respect for those who have been generations in the ‘lower case.’”

However, over several decades, as the term Negro grew out of favor, the spirit of that decision fell by the wayside. Since that time, the U.S. Census Bureau and many major institutions—including Brookings—have used the lowercase term “black” to represent more than 40 million Black Americans.

We are changing that.

As announced by President John Allen, Brookings has modernized our writing style guide to capitalize Black when used to reference census-defined black or African American people, with further revisions to a handful of other important racial and ethnic terms detailed below.

This decision comes after months of careful review and consultation. We studied historical shifts in terminology use, the modern style guides of other academic and research institutions, and the standards used by media outlets, including Black and Latino/Hispanic journalism. We interviewed experts in race, sociology, culture, and demography. We reached out to our own research community, many of whom have important experiences and perspectives as African Americans, Latino or Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, Hawaiians, and white Americans. We engaged our institution’s Inclusion and Diversity Committee. Throughout this process, we sought to better understand the origins and evolution of racial terminology, including the changing preferences of people within these different groups.

This update to Brookings’s writing style guide is one critical step in a larger set of actions the institution is taking to modernize and commit to inclusion and diversity.

The Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings (Brookings Metro), which took the lead on this research for the wider institution, takes Brookings’s commitment to inclusion and diversity—and this new terminology policy—seriously. As a program within a preeminent think tank, we know that the words we use, the research agendas we set, and the people we empower matter. Furthermore, our program’s primary audience of local and regional leaders are on the front lines of progress and demographic change. They strive to improve economic opportunity in their communities, especially for their young people who already, as a whole, represent no single race or ethnic majority. In many cities, new generations of leaders are challenging the status quo long preserved by traditional power brokers. Brookings Metro’s work must help local leaders build trust and solve problems across more diverse tables.

As we advance inclusive prosperity across the country, our team at Brookings Metro experiences how people respond to our research. Leaders welcome a data-driven narrative that unifies people around a common understanding. At the same time, long-underserved populations want to be recognized, not as problems to be fixed or statistics to be studied, but as real people who have aspirations for themselves and their families. When research on well-being omits certain populations, such as excluding Asian Americans from analysis of communities like Minneapolis-St. Paul, home to many Hmong and other Southeast Asian immigrants, it inadvertently makes them invisible. This in turn makes it difficult for local leaders to recognize and engage these populations in addressing inclusive prosperity.

It is through this journey toward being more conscientious of how people’s experiences are represented in our work that we arrived at revisiting our style guide. Yet it is only one tool among many we must deploy to ensure we do not exclude or maintain dominant frameworks that limit some people from engaging in public education, discourse, or change.

We at Brookings recognize that we have more work to do to uphold the values of inclusion and diversity, as laid out here. And within Brookings Metro, you’ll see us also strive to do the following:

- We will continue to advance a vision and mission in which more people in more places prosper; central to that is the acknowledgement that historic structures and systemic biases have limited wealth creation and mobility among Black Americans and others in our cities;

- To inform that vision, our research—where possible—will include more racial and ethnic groups in analyses to better acknowledge people’s experiences; we will disaggregate racial data where possible to not perpetuate generalizations within racial categories; we will continue to organize more data by age and gender;

- Along with our peers at Brookings, we will commit to bringing diverse experiences and perspectives to our executive leadership team, our advisory board, and our staff; this includes advancing a culture of trust and engagement where all members can contribute, exercise their voice, and have access to career learning and advancement;

- We will broaden our scholar networks so that our research and policy ideas benefit from new voices and expertise, expanding the definition of “quality” to reflect both rigor and relevance;

- We will ensure our research reaches and empowers all leaders and decisionmakers, whether from business, government, nonprofits, or neighborhoods; we will not be exclusionary in the tables we set or the civic processes we help facilitate, so that our local engagements result in the broadest benefit.

Brookings recently celebrated our centennial, a testament to our staying power through periods of political upheaval and economic reinvention. To stay relevant and impactful, Brookings must be a place where the next generation of leaders see themselves and their aspirations in our work. This commitment to inclusion and diversity, including an evolution in how we recognize and analyze people in our research, is core to our future.

America’s diverse people have always driven this country forward to new heights. Our responsibility is to highlight this strength in our work and core values. These actions reflect our part in ensuring, as Martin Luther King, Jr. envisioned, that the arc of the moral universe “bends toward justice.”

Read more about Brookings’s writing style guide updates here.

Read more about Brookings’s writing style guide updates here.