In a preview of the privacy debate getting underway in the 116th Congress, I listed “discussion drafts” of baseline privacy bills released late last year. Although these proposals will not be the vehicles for a bill that finds its way to enactment, they provide guideposts. Some provisions or ideas may end up in a successful bill, and the proposals frame many of the issues that will be at the center of debate as this process moves forward.

Together, these proposals offer a glimpse of the taxonomy of issues up for debate:

- What is the regulatory model?

- What kinds of data are covered?

- What sectors and what entities?

- What rights do individuals have?

- What obligations do businesses have in processing data?

- How are these rights enforced—by what agency and with what powers?

- How is pre-emption handled?

The question of the regulatory model is the keystone that overarches these and holds the rest together. Several of the draft bills present concrete signs of an emerging shift in the underlying model for privacy regulation in the current discussion, from one based on consumer choice to another focused on business behavior in handling data. This paper focuses on this key element of the taxonomy—how proposals reflect this shifting paradigm and how the change affects other aspects of privacy protection.

“Several of the draft bills present concrete signs of an emerging shift in the underlying model for privacy regulation in the current discussion, from one based on consumer choice to another focused on business behavior in handling data.”

This is not to diminish the significance of other elements of the taxonomy. For example, when the range of information that can uniquely identify individuals keeps growing, defining personal information—by whatever name—presents difficult drafting and operational issues, as well as questions going to the nature of privacy. It also raises questions whether, to what extent, and how information can be de-identified, as well as how to protect legally against re-identification. It spreads to the question of what is considered sensitive information and what added protections that category should have. Many questions, such as the size and type of entities covered; individual rights of access, correction, and deletion; enforcement; and pre-emption, will involve fundamentally political choices, but have technical and legal dimensions that may help or hurt the resolution of these political questions.

These are issues the drafters of further legislation are grappling with and that the discussion drafts address in various ways. In the coming weeks and months, I will be exploring these other issues further.

Setting the table: The discussion drafts

My preview listed four draft bills: two from senators, and two from outside stakeholders. To these, I have added a House bill and a privacy proposal from a group of high school students. Each of these is the product of considerable thought and input by credible players in the debate. They are, in order of release:

- Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced his Consumer Data Protection Act on Nov. 1, 2018, aimed particularly at stepping up Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforcement. Coming from a senior senator who has been an important player on technology issues, as well as being carefully drafted in language and scope, it puts down a serious marker.

- Intel Corporation—whose global privacy and security policy chief, David Hoffman, has been an industry leader on privacy—developed a draft Innovative and Ethical Data Use Act that was released for comments by invited experts and the public. Based on these comments, Intel released a revised draft this year on Jan. 28.

- Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) released his Data Care Act in December 2018 to broach the concept of duties of stewardship on the companies that collect and hold personal data. Schatz is ranking member of the Communications Subcommittee of the Senate Commerce Committee and part of a bipartisan group working on privacy legislation that includes the new chair of the full committee and the chair and ranking members of the key Commerce subcommittees. As such, he is likely to be in the middle of deliberations on a Senate bill, and was joined by 15 other Democrats on his bill.

- The Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT)—a technology policy nonprofit and bridge between industry and privacy advocates—spent the better part of a year getting input from these stakeholders, as well as academics. It later released its comprehensive discussion draft a few days after the Schatz bill back in December. (Disclosure: I participated in CDT discussions and commented on drafts. Some aspects reflect my input, others I disagree with.)

- The Information Transparency and Personal Data Control Act introduced by Rep. Suzan DelBene (D-Wash.) last September, is also included here for comparison. I did not include this bill in my preview because it was introduced before the November election, but it comes from a member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, the key House committee for privacy legislation, and I’ll take it as aimed toward the current Congress.

- I also include a proposal from students in a “tech for good” workshop at the Castilleja School in Palo Alto, California, deemed the Consumer Rights, Integrity, Safety and Privacy in Information (CRISPI) Act. It is the outcome of dueling proposals consumer and business teams synthesized by another group in the role legislators. If high school students—even if they are in Silicon Valley—are thinking about privacy legislation, it is a good indicator this issue has some popular appeal, and their bill is some reflection of popular reactions.

“If high school students—even if they are in Silicon Valley—are thinking about privacy legislation, it is a good indicator this issue has some popular appeal.”

Other legislators join the debate

Another indicator that privacy has become a mainstream issue is the array of additional members of Congress who want to be involved. Recently, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) introduced an American Data Dissemination Act that would pre-empt state laws while the FTC proposes a federal law. In addition, Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) has been touting an Internet Bill of Rights that includes sweeping principles on data. Both may be more influential than the Castilleja School students, but since neither serves on any committee likely to review privacy legislation, their proposals are not included in this discussion.

The discussion below identifies points in common and areas of divergence among these discussion drafts. It focuses on how these are reflected in measures that address the ways businesses handle personal information.

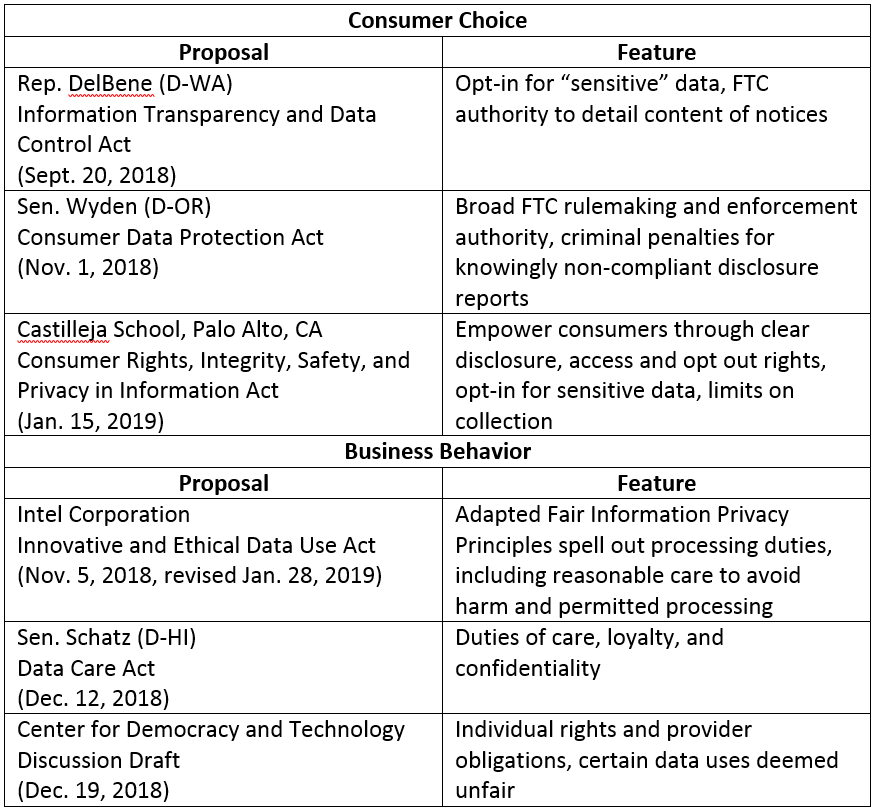

Table 1: Chief regulatory focus

What is the regulatory model?

In a Brookings paper from last year, I argued that privacy protection has become a losing game because our current regulatory model puts too much of the burden on individuals to manage their privacy protection—an impossible assignment in today’s always-on, always-connected world. I am hardly alone in this view. Privacy mavens have long and widely criticized the “notice-and-choice” model, with recent prominent critiques by Zeynep Tufekci and Woody Hartzog getting attention beyond the academy. Such critiques have been part of testimony in Senate hearings, with CDT President Nuala O’Connor testifying last fall that “few individuals have the time to read privacy notices, and it is difficult, if not impossible, to understand what they say even if they are read.” Hartzog testified this February, “While notice and choice regimes enable the collection, use, and sharing of personal information, consumers are left … exposed and vulnerable.”

“Privacy protection has become a losing game because our current regulatory model puts too much of the burden on individuals to manage their privacy protection—an impossible assignment in today’s always-on, always-connected world.”

Despite this widespread view among most who follow privacy issues closely, many proposals in the past couple of years have focused on consumer choice, often variations on opt-in or opt-out rights for individuals and increased transparency about privacy policies and practices, commonly framed as transparency and control. But last October’s Senate hearing and other discussions have laid a foundation for a focus on business behavior, and the Intel and CDT drafts point ways toward such a model. The Schatz draft is the first congressional bill in the current round to move unmistakably in that direction. Other proposals are rooted mainly in consumer choice, but also contain elements that address business behavior discussed in the next section.

The behavior-focused drafts

The Schatz bill takes a notable and novel step toward a behavior paradigm by establishing provider duties of care, loyalty, and confidentiality. Both CDT’s draft and Intel’s propose rules aimed directly at business conduct. CDT has a section that explicitly spells out “obligations of covered entities with respect to personal information,” as well as categories of data uses that are prohibited except as necessary to deliver specific features or services. CDT’s bill is also a stark departure from the notice-and-consent norm; while it requires notice as a backdrop, it prohibits certain data uses categorically instead of necessitating the kind of pop-up notifications that have become familiar for anything that requires consent. Intel’s takes a more familiar path, applying well-established Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs) as elements of required data privacy and security programs. These principles have historically incorporated notice-and-consent as well as data processing practices, which cloaks a departure from notice-and-consent in subtle, yet significant ways in Intel’s latest draft.

Unlike the Schatz draft, both CDT and Intel also spell out individual rights alongside these obligations—CDT through a section explicitly on individual rights and Intel through a provision on means for “individual participation” that a covered entity must make available.

The notice-and-choice proposals

The Wyden discussion draft takes a step in the general direction of a behavior paradigm by including a very broad mandate for the FTC to adopt regulations that include “reasonable cyber security and privacy practices and procedures to protect personal information.” Nevertheless, the Wyden draft is much longer on the disclosure elements of these practices and procedures than on how data is used. Indeed, it effectively doubles down on notice by requiring corporate officers to certify required annual data protection reports, subject to criminal penalties. This bill is the most like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of any proposal so far, in particular by matching its penalties authority at up to 4 percent of gross annual revenue. It also requires data protection impact assessments and appointment of an executive to oversee privacy and security responsibilities and addressing algorithmic decisionmaking.

As reflected in its title, the DelBene bill focuses on transparency and control, directing the FTC to adopt regulations that spell out contents of privacy and data use policies. It also requires that users provide “affirmative, express, and opt-in consent” for an operator’s use of “sensitive information or behavioral data” very broadly defined. The final Castilleja School draft also focuses on transparency and control, but applies an opt-in requirement to a narrower set of sensitive information. It would allow collection by default, requiring that companies limit what they collect and store only what is necessary to perform the services provided and not charge extra if consumers choose not to share data.

Moving beyond consumer choice

Greater transparency and individual decisionmaking have a place in comprehensive privacy legislation. These approaches address people’s desire to know more about what happens with data about them and to have some power over it. And they empower motivated and capable individuals to exercise such control. But they are far from sufficient in a digital environment in which control is so elusive. Any privacy legislation that seeks to protect individual privacy must move beyond consumer choice to address what happens with personal data once it is collected.

These discussion drafts are carefully considered steps in this direction. There is a wide range of granularity between the specific practices in Intel’s bill and the breadth of duties in the Schatz draft. This gap shows that addressing standards for behavior in U.S. legislation—how data is collected, used, and shared—is less evolved than for the individual rights under discussion. Control and processes are familiar territory that compliance officers and engineers can map into flow charts and that consumers (along with members of Congress) know from their online experience. On the other hand, the central question of what enterprises do with data is veiled with technical complexity and wide variation in the circumstances of collection and use. I can attest that this makes drafting widely applicable privacy legislation challenging from my experience in trying to put the Obama administration’s Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights into legislative language.

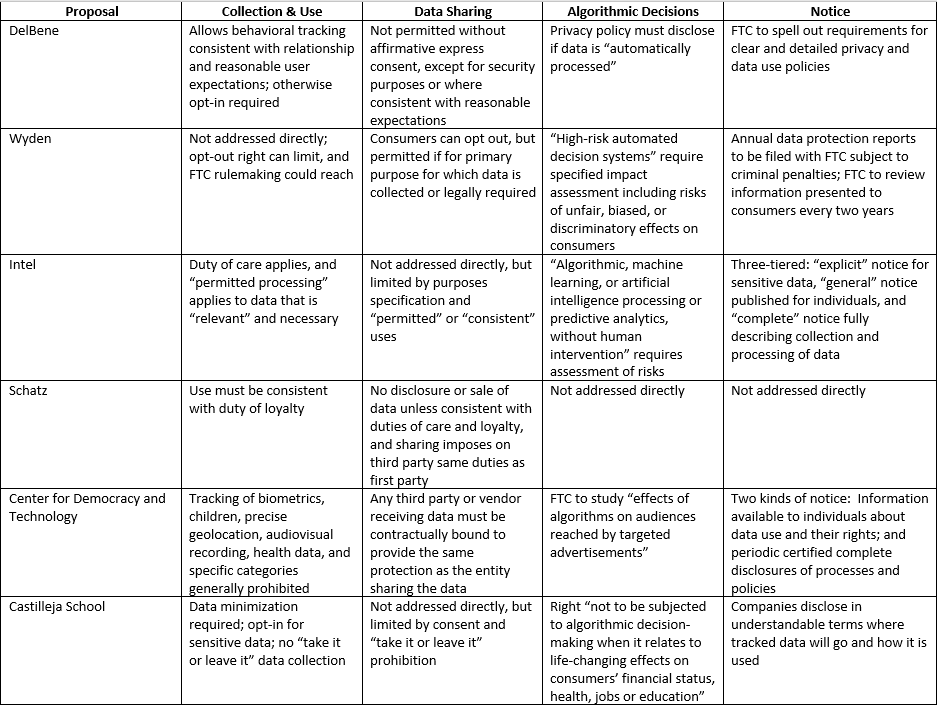

Table 2: Obligations imposed on data processors

What obligations do the entities covered have?

This section looks more specifically at how the business behavior models articulate the obligations of businesses as they collect, use, retain, and share data.

Collection and use

The most detailed draft in this area is Intel’s. The FIPPs that it adapts are enduring, and they are reflected in a variety of privacy and data protection laws, including the EU’s GDPR and its predecessor, as well as America’s longest-standing privacy laws. The Intel draft adds to these a general duty of care: “to take reasonable measures not to intentionally process personal data in a manner that would have the reasonably foreseeable consequence of directly causing a natural person to suffer significant physical injury or unmerited financial loss.” (This is a narrower articulation of harm than the bill’s definition of “privacy risk,” and has something in common with the Schatz bill.)

Intel’s draft goes on to stitch together from the FIPPs a set of collection, purpose, and use limitations that operate as guardrails. Although collection is limited to purposes specified in privacy notices, the use of data is also governed by provisions on “permitted processing,” “prohibited processing,” and “consistent processing.” Prohibited processing includes violation of the duty of care, while consistent uses are defined by an analysis of privacy risks and benefits, and a data-quality provision limits processing to personal data that is “relevant to” and “necessary for” these articulated purposes. Together, these limitations implicitly address collection.

“Provider duties” are at the center of the Schatz bill. These are framed as “the duties of care, loyalty, and confidentiality,” and they are elaborated only in general terms. Among these, it is the duty of loyalty that deals with collection and use. It is described as a duty to not use data in ways that: “will benefit the online service provider to the detriment of the end use”; “will result in reasonably foreseeable physical or financial harm to an end user”; and/or would be “unexpected and highly offensive to a reasonable end user.” This standard resembles Intel’s.

The CDT draft has a section entitled “obligations of covered entities with respect to personal information,” but it deals with more process-oriented obligations and does not establish boundaries of collection and use. As described above, another section does put secondary use of specific kinds of data generally off limits under the heading of “unfair data processing practices.”

The Wyden bill would establish a national do-not-track registry administered by the FTC, a website that would enable consumers to opt out of most sharing of personal data; in turn, covered entities would be obligated to respect these choices by technological means specified by the FTC or by consulting its website. This one-stop shop would relieve consumers of the burden to make countless individual opt-out decisions. Wyden’s bill also includes a broad grant of rulemaking authority to the FTC that includes regulations to require “reasonable … privacy policies, practices and procedures” and to implement “reasonable physical, technical and organizational measures to ensure that technologies or products … are built and function consistently with reasonable data protection practices.” This grant does not mention collection and use limitations but the FTC could find that some version of these are “reasonable data protection practices.”

The DelBene bill is similar in that it operates through a grant of FTC rulemaking authority and spells out the general substance of the rulemaking. Although the core of this is the bill’s opt-in regime and disclosure requirements for “sensitive personal information or behavioral data,” it contains a significant exception. It would exempt from the regulations the processing of sensitive information or behavioral data that “does not deviate from purposes consistent with an operator’s relationship with the users as understood by the reasonable.” This exemption appears to bring contextual considerations into the equation in a big way.

Castilleja School’s CRISPI Act contains two significant behavioral provisions in a scheme focused on affirming consumer “data autonomy.” The first is minimization of data—limiting collection, use, and retention to “the minimum data necessary to perform the services provided to consumers.” Although the final law allows collection of other than sensitive data by default, it also prohibits “take it or leave it” policies that “render and app or another digital program ineffective if consumers refuse to share the data.” This aligns with a significant school of thought about EU law.

Third-party sharing

The Wyden draft has by far the most detailed proposal on sharing data after it is collected. It allows sharing information that is necessary for the primary purpose, provided that a third party does not make additional use (secondary use) of the data. Otherwise, consumers may opt out of any data sharing via the opt-out website maintained by the FTC or by other means established by FTC regulations.

Both Wyden and CDT include a provision establishing a data broker registry at the FTC. This provides a way for individuals to identify entities they may not know about that hold data about them, and thereby exercise their rights regarding that data.

CDT would prohibit the sale or licensing of information to third parties unless the third party is bound by the same privacy and security obligations as the entity that processed the data in the first place; i.e., the obligations in the statute applicable to covered entities as implemented. The Intel proposal does not address third-party sharing directly, but may do so implicitly through its use provisions.

Algorithmic decisionmaking

Increasing concern about the impact of machine learning and algorithms on individuals and GDPR provisions that limit “automated individual decision-making” have put this issue into the mix for federal legislation. The Wyden, Intel, CDT, and Castilleja School proposals all take up the issue in some way.

Intel has the most elaborate approach. Its definition of privacy risk includes outcomes associated with algorithms and machine learning, such as “adverse outcomes with respect to an individual’s eligibility for rights, benefits or privileges” in life-affecting contexts, and “price discrimination.” In turn, its provisions on the use of data include a subsection on “automated processing,” permitting only after a specific assessment that it is “reasonably free from bias and error” and the data quality is adequate. It also includes an analysis of privacy risks and ethical and legal effects resulting in a conclusion that the processing will not result in “substantial privacy risk.”

The Wyden approach also focuses on assessment of automated processing. It directs the FTC to require assessment of “high-risk automated decision systems,” i.e., those involving evaluations of consumers that may “alter legal rights” or otherwise “significantly impact” them, or where they present significant privacy risk or risk of prohibited discrimination.

CDT touches on this issue in the context of advertising. A provision requiring the FTC to adopt rules to define “unfair targeted advertising practices” directs the agency to consider “the effects of algorithms on the audiences” and undertake measures and studies identifying discrimination.

The Castilleja School students take a page from the EU’s book, declaring a right “not to be subjected to algorithmic decisionmaking when it relates to life-changing effects on consumers’ financial status, health, jobs or education.” The DelBene bill disclosure requirements include whether data is “automatically processed” (apparently regardless of whether this processing results in automated decisions of any kind).

Notice

Although the CDT and Intel drafts reflect departures from a consumer choice model, they include business obligations for notice that restructure the traditional approach to privacy notices and policies. CDT and Intel would establish different kinds of notice that take into account the limitations of current notice practices. Lengthy and legalistic descriptions of privacy policies and practices are not useful to consumers, but they do serve an accountability function both for internal managers and external regulators and watchdogs. And simpler notices are incapable of conveying all the material information that belongs in a privacy policy but can flag important decisions in a timely way. (For example, do you want this app to have access to your location data?).

“Lengthy and legalistic descriptions of privacy policies and practices are not useful to consumers, but they do serve an accountability function both for internal managers and external regulators and watchdogs.”

Under the heading of “disclosures” (rather than “notice”), CDT proposes a two-tiered system. The first tier is aimed at individuals, requiring that clear information be “available” to individuals describing the kinds of information the covered entity collects and how it uses, shares, and protects this information, including how it enables the exercise of individual rights. The second tier is under the heading of “periodic privacy protection disclosures,” and requires publication more like the formal privacy policy statements we have come to expect, with specific elements of privacy practices spelled out. These disclosures must be made “at least annually,” and whenever they are changed materially. They are legally enforceable, as both tiers are under a provision that makes material representations in notices and other interactions with individuals under the FTC’s authority to police unfair and deceptive practices. But, reflecting CDT’s departure from a consumer choice model, they remain in the background, with no requirement that they be affirmatively provided to individuals at the time of collection or any other time. Just “available” and “publish[ed].”

Intel has three different kinds of notice: explicit notice, general notice, and complete notice under the heading of “openness.” Explicit notice is aimed at the collection of sensitive data, such as location, biometrics, racial and ethnic origin, religion, health information, and information about sexual life. General notice is similar to CDT’s disclosures to individuals—a broader, plain-language notice made available on an ongoing basis primarily informing them of their rights. And “complete notice” is a for-the-record, complete privacy policy: “A reasonably full and complete description of the covered entity’s processing and collection of data.” The FTC is directed to adopt regulations to provide more detail.

Perhaps the most notable part of the Wyden bill is its adaptation to privacy disclosures of the management disclosure obligations in Sarbanes-Oxley. It proposes to require companies to file “annual data protection reports,” certifying their compliance with the FTC’s regulations and describing any noncompliance, to be signed by corporate officers subject to criminal penalties and filed with the FTC. The bill does not address notice at the time of collection or other general disclosures, but does contain detailed specifications for what information must be given to consumers on request. This includes a list of every entity with which the consumer’s data has been shared, and authorizes the FTC to “detail the standardized form and manner” in which information will be disclosed. It also directs the FTC to conduct reviews at least every two years to evaluate whether information presented to consumers is “useful, understandable, and to the extent possible,” and does not result in “notification fatigue.”

CDT also imposes disclosure obligations on corporate managers, but without the explicit threat of criminal sanctions. The periodic disclosure statements must be certified by a corporate officer, but there is no requirement of filing with the FTC or any other federal agency.

The DelBene bill has detailed requirements for privacy policies, to be spelled out by FTC rulemaking. A policy must be “presented to users in the context where it applies,” and must be concise, clear and visual to make complex information understandable to the ordinary user. At the same time, they must provide contact information, and specify a host of information, including: the purposes of the collection and use and the retention period; the third parties with which information is shared; the means of access and withdrawal of consent; the types of data collected; and how the data is protected. All of this is valuable, but the requirements blend different functions of information and add to the information overload people face today.

Fleshing out the obligations

How to provide for collection and use of personal information will be at the crux of the privacy debate. In theory, opt-in or opt-out choice provides a check on unlimited data collection or use and sharing of information that is inconsistent with individual expectations. Individual rights like access, correction, and deletion provide a further check on use and sharing. But experience and research have demonstrated that these checks alone are not doing the job. This is why privacy legislation is now on the agenda in Congress.

“How to provide for collection and use of personal information will be at the crux of the privacy debate.”

A change in the paradigm of privacy regulation from consumer choice to business behavior means that law will have to supply these checks. CDT’s categories of per se, unfair data processing activities is one effort to put certain uses out of bounds, but its draft bill does not touch on collection. Intel’s data quality and use provisions put up a variety of guideposts along the frontiers of data collection. The DelBene bill suggests a role for contextual integrity, and the Schatz bill suggests ethical boundaries. The Castilleja School students address collection and use directly with their data minimization provision. No matter where boundaries are drawn, some existing business models and practices are bound to fall outside. That will make for some complex drafting discussions and difficult political choices ahead.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Intel provides financial support to The Brookings Institution.

Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).