Today, March 6, 2024, the European Union’s (EU) Digital Markets Act (DMA) hits a major milestone as digital platforms defined as “gatekeepers” must report on their compliance with the Act’s provisions. The action is a road test for Big Tech regulation that portends to establish the EU as the de facto international regulator. But the process is far from over.

What is the DMA?

Enacted in July 2022 by the European Parliament, the DMA establishes Europe-wide oversight of the dominant digital platforms. The avowed purpose of the DMA is to promote competition, fairness, and innovation.1

In May 2023, the major components of the DMA went into effect. The following September 6, the European Commission (EC), the administrative body of the EU, began enforcing the law by designating six companies as market-dominant “gatekeepers” required to comply with the Act’s provisions. The gatekeepers had six months—until March 6, 2024—to bring their operations into compliance.

The DMA is the beginning—but far from the end—of the European oversight process. The gatekeeper companies are now required to deliver detailed reports on their compliance. Next steps can be expected to include regulatory assessment of the adequacy of those actions, including the DMA’s new “market investigations” authority. Beyond these targeted investigations, the DMA directs the EC to begin an 18-month investigation of the resulting digital market behaviors. By May 3, 2026, the Commission must report to Parliament on the effectiveness of the DMA-initiated actions and recommend whether changes are needed.

Who are the gatekeepers?

Responding to concerns about the potential negative impact of regulations on smaller firms, the DMA focused on larger firms with “gatekeeper” power. To make this determination, the DMA established three criteria:

- Whether the company “has a strong economic position, significant impact on the internal market and is active in multiple EU countries,”

- Whether it “has a strong intermediation position, meaning that it links a large user base to a large number of businesses.” and

- Whether is “has (or is about to have) an entrenched and durable position in the market, meaning that it is stable over time if the company met the two criteria above in each of the last three financial years.”

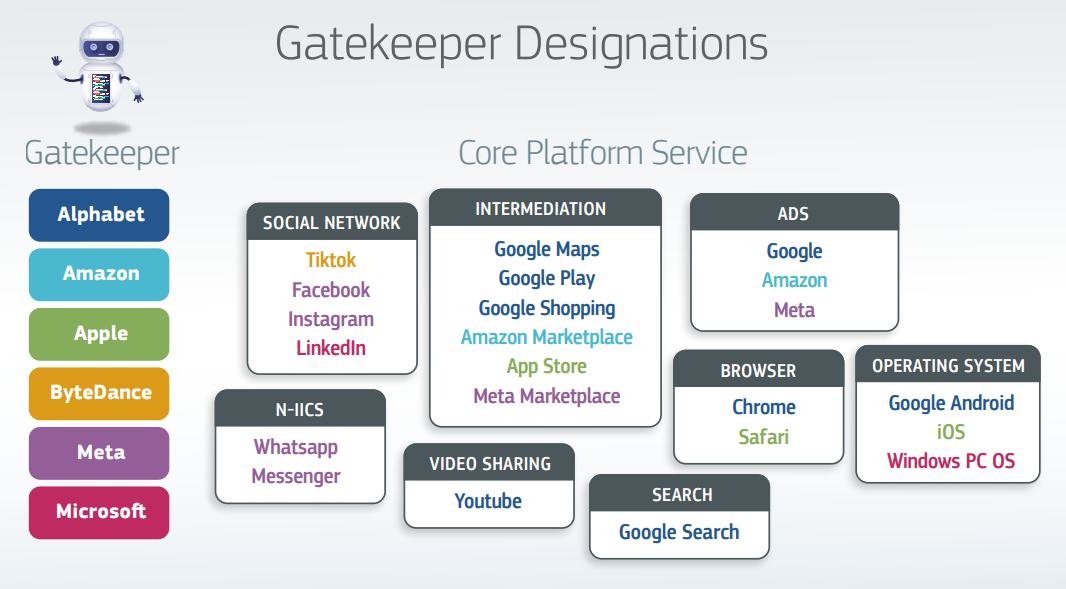

Six digital platform companies, and 22 of their offerings, were deemed to have gatekeeper power.

As a result of such designation, the companies, among other requirements, must:

- Facilitate interoperability with third parties,

- Allow businesses access to the data generated when using the gatekeeper’s platform,

- Allow advertisers access to the data their ads generate,

- Allow third parties to offer their own billing for services promoted in app stores,

- Not self-preference their own products and services on their platforms,

- Not prohibit consumers from linking from one app to another app outside the platform,

- Not prohibit consumers from uninstalling default apps,

- Not track user activity for advertising purposes outside the specific service without consent.

On March 6, the gatekeepers must report their compliance with such rules. Failure to comply could result in fines up to 10% of worldwide revenue (20% for repeated violations). Beginning on March 7, no doubt, the regulatory (and ultimately judicial) back-and-forth as to what constitutes compliance will begin. Both results will have spillover effects in the United States.

The insufficiency of litigation

The nations of the EU were ahead of the United States in seeking to address digital platform abuses through existing laws. For instance, in 2017 the EC fined Google €2.42 billion ($2.7 billion) for preferencing its own shopping service over that of others. The following year it fined the company again, this time €4.34 billion ($5.1 billion) for anticompetitive practices involving its Android mobile operating system. Then, in 2019 Google was fined €1.49 billion ($1.69 billion) for restricting in its AdSense advertising sales contracts the placement of ads on other websites.

The EU’s passage of the DMA can be interpreted as a recognition of the inadequacy of using such an approach, by itself, to address new digital challenges. For a while, elected members of the European Parliament, like their congressional counterparts, appeared to hope that prosecutors and courts would resolve the tough policy issues. That experience led to the conclusion that the old industrial era statutes were insufficient for the new digital economy. The DMA introduces statutory specificity as to what constitutes reasonable behavior in digital markets.

The European experience demonstrated the difficulty of delivering broad results on a case-by-case approach. Reliance on such focused enforcement is slow (especially in comparison to the speed of technological innovation) and backward-looking (at a time of rapid redefinition of technology and markets). Furthermore, the fines, while large in absolute numbers, end up being gnat bites when compared to the gargantuan revenues and profits of the dominant digital platforms. These are lessons still being learned in the U.S. as antitrust actions creep through the courts while the practices alleged to be abusive continue, new technology drives new behaviors, and congress sits idle.

Sectoral regulation

The DMA is a regulatory watershed in the digital marketplace because it adopts specific policies for that specific sector of the economy. In place of applying broad oversight concepts rooted in competition law, the DMA has focused on the reasonableness of the practices of digital platforms. It is a policy shift from protecting competition in the hope consumers would benefit, to specifically protecting against identifiable practices.

Rather than adjudicating past behaviors, the DMA seeks to establish a digital market with ongoing contestability and fairness. Instead of focusing on a specific action by an individual company, it establishes industry-wide expectations. Rather than requiring a finding of specific harm, the DMA focuses on the reasonableness of an action. In the process, it has transformed the EC, heretofore a generalized administrative body, into a regulatory body with sectoral expertise.

The deemed insufficiency of the earlier targeted litigation strategy has led to new statutory stipulations. In the belief that establishing the definition of reasonable behavior will protect both competition and consumers, the DMA has established what competitive and fair markets should look like for an entire sector of the digital economy.

Let the games begin

A regulatory ballet can be expected to begin on March 7, the day after the DMA’s effective date. Many of the gatekeeper companies have already initiated compliance plans. It will now fall to the EC to determine the adequacy of such plans, possibly including its new market investigation powers.

The compliance plan from Apple, for instance, is the opening chords of the forthcoming ballet. To comply with the DMA, Apple has ended its prohibition of third-party billing platforms. As anyone who has tried to purchase a Kindle book, Spotify music, or other third-party content through their iPhone knows, it is not possible. This is because these companies refuse to pay up to the 30% Apple assesses on the gross revenue generated by an app in the App Store. The DMA requirement that apps be allowed to link to third-party billing services outside of the delivery platform has forced Apple to change its behavior.

The old App Store policy has been replaced with a new program that offers app developers three billing alternatives. The first alternative is the status quo to continue paying up to 30% of App Store generated revenue to Apple. The second choice is to pay Apple 17% of such revenue plus 50 eurocents annually on all transactions above one million. The third option is to use a competitive billing system while still paying Apple the annual 50 eurocents per download.

Many app developers see Apple’s new plan as a violation of the intent of the DMA. The CEO of Epic Games, which has been trying to use antitrust litigation to open up Apple’s practices, called the new policy “Malicious Compliance.” Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg called the action “onerous” and “at odds” with the DMA. On the day after DMA compliance goes into effect, European regulators will have to wrestle with whether the new policy is, in fact, reasonable behavior.

Apple is not unique in this situation. For the last several years, platform companies have lobbied to oppose the DMA. That effort will now adjust to arguing (and probably litigating) the reasonableness of their compliance.

An American impact?

That the new Apple policy will not apply to the U.S. is an illustration of how the nation is still in the litigation, not legislation phase of digital policy development. When game developer Epic sued Apple alleging its AppStore practices were anticompetitive, the U.S. District Court in 2021 found in favor of Apple. The court did, however, rule that Apple could not block app developers from using a third-party billing platform. In response, Apple allows such connections but still required paying Apple a 27% commission (which when combined with the outside billing service fee can take the cost for many app developers above the 30% charged by Apple for its billing). The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal. Epic will, most likely, go back to the District Court with a complaint about Apple’s response. But, unlike the EU, there is no standard of what constitutes reasonable behavior and no ongoing oversight of such actions.

This experience identifies that DMA decisions will not always have an effect in the U.S. In other instances, however, American consumers could be beneficiaries of Europe’s actions. As gatekeepers must choose between common business practices or a more costly Balkanization of the online marketplace, changes made to comply with the DMA could inure to the benefit of American consumers.

The DMA has also rewritten how the discussion about American digital policy will henceforth proceed. After March 6, the starting point for every American legislative or regulatory inquiry into the practices of dominant digital platforms will begin by identifying the policies with which those companies must already comply in Europe. The DMA, thus, can become table stakes in the American digital policy debate.

Whither goes American policy?

For the last 20 years, digital platforms—a sector dominated by American firms—have successfully opposed regulatory oversight of their activities. These companies succeeded in their strategy domestically, but their lobbying failed in Europe.

March 6th begins a new day for doing digital business in the world’s second largest economy. The spillover extension of European consumer rights to Americans—ranging from “you do it over there” to simple internet economics—means the DMA holds the potential to change the environment in which digital platform companies are judged in the United States.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Google, Meta, and Microsoft are general, unrestricted donors to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the author and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- The DMA should not be confused with its contemporaneous twin, the DSA – Digital Services Act – that covers more than gatekeepers to address content moderation issues and the safety and security of digital platforms.

Commentary

Road testing Big Tech regulation in Europe

March 6, 2024