This piece is part of a series of policy analyses entitled “The Talbott Papers on Implications of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” named in honor of American statesman and former Brookings Institution President Strobe Talbott. Brookings is grateful to Trustee Phil Knight for his generous support of the Brookings Foreign Policy program.

Peace for Ukraine may be a long way off, as we write these words in the spring of 2023. Yet the time to begin preparing for peace is not after the last gun falls silent. Long before they had triumphed in World War II, Allied leaders began to contemplate the shape of the future peace — even though in that case, they had already settled on the absolutist goal of unconditional surrender as the inevitable end state of the conflict. At conferences in Tehran, Yalta, Potsdam, and elsewhere, they discussed proposals and made plans to create international institutions that could prevent another war. Today, a similar effort is needed, beyond the ideas that have been developed and voiced to date. Western leaders must develop security mechanisms and consider strategies to assist Ukraine in sustaining its independence, and to manage future relations with Russia. With the right approach, the prospects for any eventual peace negotiations may also be substantially improved.

We offer one proposal here for how to protect Ukraine — while also improving the odds that Russia can someday again become a responsible part of the European security order, or at least reducing the odds that it will increasingly go rogue across a range of issues. The concept centers on the idea of deploying a substantial, armed training and monitoring mission of at least several thousand Western troops, including Americans, to Ukraine after a ceasefire or peace accord — but doing so under the auspices, and with the protection, of a new security architecture and perhaps also the United Nations, rather than NATO.

Current thinking about security architectures to help Ukraine focus on NATO membership for Ukraine, on the one hand, and a “porcupine” strategy on the other, by which NATO countries would enhance arms exports to Ukraine so as to maximize the odds of successful self-defense. These two ideas present an inadequate range of possibilities. Russia has assaulted Ukraine and committed heinous war crimes against Ukrainians. Russia must be held accountable and punished for these crimes. But we must not allow wrath toward Russia to cloud thinking about NATO expansion. Although NATO expansion to Russia’s boarders did not directly cause Russia’s violent assault on Ukraine, it is hard to argue it played no role at all. NATO expansion was well-intentioned and designed to enlarge the zone of democratic peace in Europe while acknowledging the right of independent states to have a major say in their own security arrangements. But when juxtaposed with the pride and paranoias of Russians like Vladimir Putin, it inadvertently contributed to a Russian geostrategic and historical narrative that, however inaccurate, was both predictable and dangerous.

Although Kyiv’s desire to join NATO is understandable, any such membership is virtually guaranteed to ensure a hostile relationship with Russia indefinitely, even after Putin, because it is an alliance that Russia will never be allowed to join.

And although Kyiv’s desire to join NATO is understandable, any such membership is virtually guaranteed to ensure a hostile relationship with Russia indefinitely, even after Putin, because it is an alliance that Russia will never be allowed to join. Such an outcome would be highly unfortunate. It would likely increase the odds that Moscow will seek to undercut Ukraine’s security, if not by classic aggression, then by subterfuge and covert action. It would also make security collaboration with Russia on other matters such as nuclear non-proliferation very difficult; note, for example, how unthinkable it has already become to work with Moscow in pressuring Pyongyang and Tehran not to pursue their nuclear ambitions. Even if a truly collaborative partnership with Moscow is now likely decades away under the best of circumstances, the degree of animosity in the relationship matters greatly. The West has a clear interest in limiting the damage, especially after the inevitable end of Putin’s rule, though it may take more than one leadership change after Putin to begin to restore the West’s relationships with Russia to a truly workable state.

If NATO membership would go too far, the porcupine concept does not go far enough. It is modeled in some ways after America’s commitment to give non-ally Israel a “qualitative military edge” in defense technology. Such a model should be part of any overall strategy. But Israel has advantages (such as nuclear weapons) in its relations with its fractured neighbors that Ukraine does not have against the Russian behemoth. Thus, this concept should be coupled with security enhancements and institutional commitments from Western and Eastern powers as well, given the degree of Putin’s duplicity and untrustworthiness. As some Ukrainian officials have argued, only China (and possibly India) can assert adequate, long-term, friendly pressure on Russia to back away from Ukraine. However, depending on Beijing to ensure the peace is a bridge too far. For that and other reasons, the porcupine strategy is insufficient.

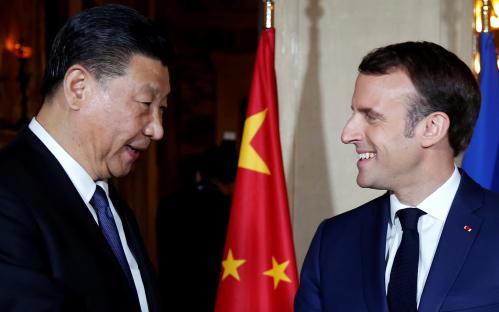

Our proposal envisions a new security organization that would include both European and ideally also Asian states. Its first action would be to deploy an armed training and monitoring mission into Ukraine for a long-term and open-ended presence, in part to serve as a tripwire against renewed Russian attack. It would include uniformed military personnel from the United States and some other Western powers but would not be organized or commanded under NATO auspices. Rather, an Atlantic-Asian Security Community (AASC) could be formed out of some combination of like-minded Western states, notably Canada, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and frontline countries near Russia, as well as Ukraine. There would be arguments in favor of extending the membership to other states beyond Europe — especially India (which might even be offered command of the training and monitoring mission for Ukraine), though perhaps even China and the central Asian states such as Kazakhstan too. But the United States, NATO’s largest European powers, and most of the frontline states near Russia and Ukraine would be the founding members.

The AASC’s key purposes would be to backstop the principle of peaceful, sovereign borders and oversee a training and monitoring mission, which should include at least several thousand Western troops (generally not organized into combat units but prepared to group into more defensible formations if hostilities loomed). The twin initial objectives would be to deploy and supervise a military presence that would deter Russia from further attacks, especially in the short to medium term, while creating a framework and vision for a future security architecture separate from NATO that could perhaps include Russia someday. All other aspects of AASC would be secondary. They could also be adjusted over time.

AASC member states would pledge to defend this training and monitoring mission if it found itself under attack and develop plans in advance for how they would do so. It would be understood that its members could defend their own troops without waiting for permission or authorization from the larger AASC organization, but through AASC they could also request a joint response to any transgression. Also, if individual forces were threatened sporadically in localized incidents, and the Kremlin were suspected to be behind such incidents, AASC members could consider temporary deployments of national combat units into Ukraine to provide more robust protection. They would also preemptively lay-out proportionate responses to gray-zone, small-scale, and larger-scale aggressions that Moscow might employ.

The AASC could be created with or without Russian acquiescence — though preferably with. In addition to its immediate purpose, it would also be intended to support the vision of a future post-Putin Russia that could once again be a responsible contributor to European and global security. Moscow would be much more likely to consider joining such an organization, somewhere in the far post-Putin future, than to join the very NATO alliance that was its competitor and rival for so many decades. Alternatively, the AASC could be modified and renamed at such a future juncture if that seemed a more promising path to Russian rehabilitation.

Such decisions would have to be made at a later date. But the creation of the AASC in the near term would help set up the appropriate framework for discussion if and when circumstances were conducive. Such a vision may someday be important for those Russians who would themselves wish to bring their nation into the democratically-oriented international community but face internal opposition and skepticism from hardline nationalists who believe that permanent conflict with the West is both inevitable and desirable. That argument is wrong and must be directly countered, sooner rather than later.

THINKING BEYOND THE WAR — AND PREVENTING THE NEXT ONE

An end to the war may be a long way off, because, as of this writing, both Russia and Ukraine are confident that victory is still possible. Putin’s Russia trusts that the resolve of Ukraine’s Western backers will break before its own, which will deprive Kyiv of the materiel and money that it needs to continue the conflict. Ukraine disagrees, believing that the steadfastness of its citizens and their partners in the West — combined with the popularity and persuasiveness of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy — will enable it to retake the land that Russia illegally and viciously seized. With neither side ready to compromise, the fighting is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

But things can change fast, and the world needs to be ready. As we outline above, the central pillars of Western strategy thus far are NATO membership for Ukraine, arming Ukraine like a porcupine, and Russian containment through economic isolation. The former is ill-advised, and the latter two are insufficient. Further extending NATO would virtually guarantee an antagonistic relationship not just with Putin but with all plausible future Russian leaders. It, therefore, does not make Ukraine or the West safer. Both the storied Sovietologist and diplomat George Kennan1 and the pro-Western Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev2 warned against expanding the alliance when new countries began joining in the 1990s. CIA Director William Burns made a similar warning about Ukraine in particular in 2008, when he was serving as the U.S. ambassador to Russia, writing in a diplomatic cable that “Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin). I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.”3 A stable peace in which Moscow is truly invested cannot be built on this option. Advocates of this Ukraine-in-NATO approach must resort to a pure deterrence logic over an indefinite duration, since taking Ukraine into NATO would certainly raise the odds as well as the magnitude of long-term acrimony between Russia and the West.

The United States and its allies and partners need to think creatively about how to guarantee Ukraine’s security beyond the paper promises that have been made in the past and trashed by Moscow.

At the same time, the United States and its allies and partners need to think creatively about how to guarantee Ukraine’s security beyond the paper promises that have been made in the past and trashed by Moscow. Russia has repeatedly signed and violated agreements pledging to respect Ukrainian sovereignty. Most importantly, the 1994 Budapest Memorandum — signed by Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom — promised Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan a “security assurance” and sovereignty in exchange for transferring to Russia the thousands of nuclear warheads stationed on their territories. If they had not given up these weapons, it is unlikely Russia would be in such a strong position to attack and/or threaten them as it has in recent years. Those countries (but in particular Ukraine, given the circumstances) deserve a serious security commitment and not simply paper assurances.

The other main proposal for a security guarantee is to turn Ukraine into a “porcupine” by arming it to the teeth. This strategy aims to create a relationship between Russia and Ukraine similar to that of Israel and Iran, North and South Korea, or East and West Germany during the Cold War. This approach, coupled with economic sanctions and diplomatic exclusion, effectively seeks to turn Russia into an isolated, pariah state — a “rogue Russia,” in the words of the Eurasia Group.4 But that approach itself does not provide enough help to Ukraine. Moreover, thinking of Russia as a permanent rogue state is problematic. With 11 times zones and 6,500 nuclear warheads, Russia cannot be contained or isolated this way. Further, if the West helps Russia go rogue, we weaken our own security as Russians will be motivated to undermine the West any way they can, for the foreseeable future. Cooperation on matters such as countering North Korean and Iranian nuclear ambitions, where the West and Moscow often did work together for the first two decades of this century, will likely remain elusive for many years to come.

Yet even as we seek to imagine a way that Russia could someday rejoin the community of responsible nations — or at least not fall even further into extremist attitudes and behavior — deterrence is also needed. Some type of Western and non-Western military presence on Ukrainian soil is needed to ensure the nation’s defense. The question is how to structure this presence, embed it within existing or new security organizations, and ensure its efficacy.

NATO’s original purposes were summarized by its first secretary-general, Lord Hastings Ismay, in the alliance’s early days. It was designed, he said in 1949, “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” The world now needs an agile military coalition or alliance that keeps Putin out — but that can eventually draw reform-minded Russians in, alongside the Americans, to keep Ukraine and its neighbors safe. At a minimum, we need to avoid making the problem of Russia’s embitterment and ostracization worse by policy actions that are within our own control. Deterrence is crucial; antagonism is not.

THE ATLANTIC-ASIAN SECURITY COMMUNITY

To clearly distinguish it from NATO, the AASC should not be called a treaty organization and should likely not obligate members to come to one another’s defense in case of attack. Rather, military transparency and joint patrols would be the main, daily security-enhancing mechanisms. Some of the founding states would be nuclear powers, and as such, they would deter Russian aggression and provide a credible security guarantee by deploying their own military personnel to Ukraine as long as Moscow remains aggressive.

The AASC would need to carry out strategic planning, conduct regular joint military exercises, and share classified materials among its members. In addition to safeguarding Ukraine against the threat of renewed war, it could be tasked with other missions, should its members elect to do so. For instance, it might help provide the military muscle to enforce a future peace deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan, should one be hammered out in other forums such as the United Nations or the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). It could also potentially assist with migrant crises, or address terrorist threats.

But in the near term, the AASC’s primary purpose would be to supervise and coordinate the deployment of at least several thousand international troops as trainers and monitors on Ukrainian soil. These troops would hail from the United States and other European and Asian AASC members. The presence of Western military personnel in Ukraine is essential for deterrence. China and India may prove key partners for obtaining Russian buy-in. (Note that for eight years, both Russia and Ukraine agreed to an unarmed OSCE monitoring mission, so both sides are already accustomed to international monitors — though clearly, that mission was not enough.) Troops from the United States as well as other NATO countries should deploy as a part of the international force, and the United States should be prepared to come to their — and thus Ukraine’s — defense in the event of attack.

Two approaches to forming such a force might be considered. One would be to create a peace implementation force, approved by the U.N. General Assembly rather than the U.N. Security Council, that Moscow could neither veto nor stonewall, while providing a path for possible Russian rehabilitation. The force might be given a multi-year mandate to patrol the Russian-Ukrainian border, perhaps also monitoring the fair treatment of various populations to reassure all parties including Moscow. (Note that the first armed, blue-helmeted U.N. peacekeeping mission deployed to the Suez Canal to oversee the demobilization of imperial-minded French, British, and Israeli forces from Egypt. The United States and Canada led the way for its allies to step back from their disastrous and imperial military actions in the Suez. Because the U.K. and France were veto-wielding members of the U.N. Security Council, this mission was approved by the U.N. General Assembly under the “uniting for peace” provision.

It will eventually be important to monitor Russian troop demobilization and withdrawal from Ukraine. Ukraine will also need aspects of demilitarization because it is going to be awash in weapons (many unregulated) after the hot war ends. As history shows, it is difficult to demobilize and disarm unless a third party agrees to monitor compliance with accords and guarantee safety. Ukrainian (and Russian) society would also benefit from externally-funded reintegration programs for former combatants. Demobilization, demilitarization, and reintegration are what U.N. peacekeepers have done well for decades.

An alternative approach — and perhaps the simpler model to focus on for our present purposes — would be to place the international force directly under the AASC, with only the approval of the Ukrainian government. This option would also thus be legal, under international law. Its day-to-day tasks would be training Ukraine’s military and police while monitoring the treatment of various populations including minority groups. It should be deployed throughout much of the country, so as to deter Russia from encroaching on Ukrainian territory. The training forces should also be in regular contact with NATO combat forces based in the eastern regions of member states’ territories. This would ensure that rapid-reaction forces could be sent to protect trainers if need be. Any attacks against training personnel would be investigated and, if Moscow were found complicit, punished proportionately. This force would ideally be headed by a general from a nation that has managed to maintain passable relations with Western countries as well as Russia — hence our notional suggestion of Indian leadership for this role.

It is in the East European, the American, and the global interest to encourage a responsible, international-law-abiding Russia to emerge from its disastrous assault on Ukraine.

As soon as a Russian leadership renounces imperial claims on its neighbors, in the judgment of AASC members, Russia would become eligible to join the AASC. Perhaps that would be in 2030. More likely, it would be in 2035, 2040, or even later — once not only Putin but much of Putinism might have been removed from the influence and prominence they have in today’s Russia. NATO’s eastern members might be skeptical of Russia and seek to block an invitation even at that point. But it is in the East European, the American, and the global interest to encourage a responsible, international-law-abiding Russia to emerge from its disastrous assault on Ukraine.

Should Moscow apply for membership, AASC countries should consider Russia’s military posture near Ukraine’s borders, its willingness to unconditionally recognize the sovereignty of Ukraine, and its territorial disputes with other countries when making its decision. The AASC would not replace or weaken NATO, even if Russia ultimately joined. Moscow would have to understand that reality. Its aggression against Ukraine and recent history of imperial behavior in Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and elsewhere make NATO’s continued existence in its current form non-negotiable. That said, if Russia is on the road to recognizing the sovereignty of its neighbors, the AASC would take pains not to exclude the country’s new leadership. In time, the AASC could perhaps even come to exceed NATO’s importance for regional security. But that day would have to be seen as decades off.

A LONG-TERM VISION FOR RELATIONS WITH RUSSIA

An AASC-led international force would both harden Ukraine’s defenses and seek to deter any revival of Russian imperial aggression. The force’s mission would not be to defeat Russia militarily, or to undermine the Russian Federation’s territorial integrity, but rather to uphold the sanctity of international borders under international law. If necessary, reinforcements from NATO members could help to defend Ukraine. By dint of its makeup — comprised largely of U.S. and other Western troops — the training force would virtually guarantee that the United States and the rest of NATO would enter any future war if Russia were to renew its attacks against Ukraine or its other neighbors. It would thus be a highly credible tripwire.

At some point later in 2023, or perhaps 2024, war may begin to seem futile to Moscow and Kyiv, as some variant of a stalemate settles in. Or Ukraine might succeed in pushing Russian forces out of its territory. In either case, policymakers need to be ready with a new security vision for the region, beyond the two ideas in frequent circulation today (NATO membership and the “porcupine” strategy with a qualitative military edge). The issues are too complex to be worked out on the spot if and when peace talks begin. We need to develop and debate them now.

Moreover, a new security vision may improve the prospects for peace by showing how both Ukraine and post-Putin Russia can see their core interests protected and upheld. Even if the deployment of an AASC training and monitoring force to Ukraine does not engender Moscow’s initial support, we contend that it will prove less inflammatory to Russia over time — and thus more consistent with preventing further deterioration in the West’s relationship with Moscow, while someday also helping empower Russian reformers as they try to reorient their country toward once again accepting norms about international sovereignty.

Russia has transformed itself mainly through radical regime change, as in 1917 and 1991. But it has also changed in important ways without revolution or outright military defeat, as when Nikita Khrushchev assumed power after Stalin, or during Gorbachev’s rise to power in the mid-1980s. We also note that several times after military defeat, Russian domestic politics changed dramatically. The 1856 rout in Crimea ushered in the liberalizing reign of Alexander II and the end of serfdom; the loss to Japan in 1905 spelled the first Russian Revolution; and the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989 gave wind to glasnost and perestroika. Thus, regime change and radical social transformation are possible in Russia, as is reform from within the system. Or Russia could devolve into a far worse state, ranging from extreme military dictatorship to disintegration. Regardless, no matter how Russia evolves after the current war in Ukraine, the United States and its allies need a policy that maximizes the odds of favorable change by presenting a West that is firm and resolute yet at the same time not innately hostile.

An Atlantic-Asian Security Community could provide a serious security commitment to Ukraine, while holding out a vision for eventual Russian membership should the opportunity arise.

Debates on security architectures must begin now so that concepts can be discussed and developed before negotiations begin. Otherwise, they will have little chance of success, and we will be left with just the two inadequate choices of NATO membership for Ukraine and the porcupine strategy. Again, our view is that while the first is too much and the second too little, both lead to less security over time. An Atlantic-Asian Security Community could provide a serious security commitment to Ukraine, while holding out a vision for eventual Russian membership should the opportunity arise.

Editor’s note: An original version of this article stated that the rout in Crimea occurred in 1865, when it occurred in 1856. It has been corrected.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors would like to thank Constanze Stelzenmüller, James Goldgeier, Jeffrey Feltman, Fiona Hill, Melanie Sisson, William Taylor, Jorgen Andrews, and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments, as well as Adam Lammon for editing and Rachel Slattery for layout. They are also grateful for feedback during presentations at Brookings, Columbia University, the U.S. Institute of Peace, the Atlantic Council, the Dartmouth-Stimson Security Forum, and the Annual Meetings of the Alliance for Peacebuilding and the International Studies Association.

-

Footnotes

- James Goldgeier, “The U.S. Decision to Enlarge NATO: How, When, Why, and What Next?” The Brookings Institution, June 1, 1999, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-u-s-decision-to-enlarge-nato-how-when-why-and-what-next/.

- “NATO Expansion: What Gorbachev Heard,” National Security Archive, George Washington University, December 12, 2017, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2017-12-12/nato-expansion-what-gorbachev-heard-western-leaders-early.

- Joshua Shifrinson and Stephen Wertheim, “Acting too aggressively on Ukraine may endanger it — and Taiwan,” The Washington Post, December 23, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/12/23/ukraine-taiwan-red-lines/.

- Ian Bremmer and Cliff Kupchan, “Top Risks 2023,” (New York: Eurasia Group, January 3, 2023), https://www.eurasiagroup.net/issues/top-risks-2023.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).