Recent years have seen the arrival of a wave of new therapies that use living cells or genetic material to treat disease, which are commonly called cell and gene therapies (CGTs). Many more of these therapies are in the pipeline. Many current and expected CGTs have the potential to deliver major health benefits, including for people with cancer or serious genetic conditions such as sickle cell disease, as well as downstream cost savings. But these therapies often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars or more for a course of treatment.

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has said that it is exploring novel approaches to paying for CGTs in Medicaid, driven by concerns that state Medicaid programs would otherwise tightly limit access to these costly therapies. This is no idle concern. Likely because of states’ desire to contain program costs, Medicaid often applies tighter utilization controls (and pays less) than other payers do, which can sometimes keep enrollees from accessing valuable treatments. The wave of access restrictions that greeted the highly effective, but costly, new therapies for Hepatitis C that emerged starting in 2013 offers a cautionary tale.

The new payment models that CMMI is considering are all “outcome-based” models that would tie payment for a therapy to realized patient outcomes, with manufacturers being paid more if a therapy performed well. One of the models (an “annuity” model) would also spread payment for a therapy over time, rather than having payment occur in one or two lump sums.

In this analysis, we examine how CMMI’s proposals—and other potential policy approaches— might affect access to these therapies in Medicaid. We make four main points:

1. Outcome-based payment can help expand access in some scenarios where a therapy’s benefits are uncertain, but it is unclear how common these scenarios are. Moreover, it will typically increase program costs even when it does not expand access.

When deciding whether and how to cover a therapy, a state should generally care about its expected cost of doing so, averaged across all potential scenarios for how the therapy might perform. Arrangements that offer states lower expected costs will typically also offer manufacturers lower expected revenues—and thus be rejected by manufacturers—which limits the scope for outcome-based payment models to facilitate greater access.

Nevertheless, outcome-based payment may sometimes facilitate broader access by helping states cope with uncertainty about a therapy’s benefits, which may be greater for CGTs than for other therapies. Notably, manufacturers may sometimes have information suggesting that a therapy is more effective than the state believes it to be. In these cases, outcome-based payment might enable broader access by offering the state a low price if it turns out to be correct and the manufacturer a high price if it turns out to be correct; in effect, outcome-based payment allows the manufacturer to “put its money where its mouth is.” Outcome-based payment might also ameliorate policymaker concerns that they will be criticized if they pay for a therapy that turns out to be ineffective. On the other hand, these arrangements may expose policymakers to criticism that they paid more than necessary in cases where a therapy turns out to be highly effective and so the state pays a high price.

Outcome-based arrangements would likely increase program spending since manufacturers will only agree to outcome-based contracts if they expect to earn more than they will under Medicaid’s usual rules. These arrangements would also be complex to administer. Thus, these approaches may often increase program costs even when they do not expand access.

2. Annuity payment could help expand access if spreading payment over time made a therapy’s costs easier or more appealing to bear, which could be the case in some specific scenarios. A non-outcome-based annuity would likely be easy to administer.

Annuity payment could help expand access if the state’s (perceived) benefit from spreading payment over time outweighs the increase in total payments that manufacturers would likely demand to defer payment. This could be the case for therapies where providing robust access would cause a state to face large costs during a short period of time. Such costs could sometimes be difficult to accommodate given states’ limited ability to borrow and other frictions in state budgeting processes. Large transitory costs are most likely for curative therapies with large eligible populations, and therapies targeting populations large enough to make smoothing valuable to states may be relatively rare.

Perhaps more important in practice, policymakers may also value being able to delay payment if they place a low weight on future costs relative to current costs, for example because election cycles give them short time horizons. This may be especially important for therapies that substantially reduce the ongoing cost of managing the treated condition. In such cases, annuity payment may transform a therapy with large near-term costs into a therapy with more modest near-term net costs or possibly even near-term cost savings.

Importantly, while CMMI envisions implementing annuity payment as part of an outcome-based payment model, any access benefits of annuity payment per se could be achieved in a standalone model. Such a model would be relatively easy to administer.

3. Addressing many likely drivers of access restrictions, such as states’ general desire to contain spending or opportunities to shift costs to other payers by delaying treatment, would require policy tools beyond outcome-based and annuity payment.

Many reasons that states may restrict access to CGTs are not addressed by outcome-based and annuity payment models. Notably, states may place a high weight on limiting costs for taxpayers relative to benefitting Medicaid enrollees; this possibility is not specific to CGTs and is likely the main reason that Medicaid is generally a relatively restrictive payer. Factors specific to CGTs may also play a role in access restrictions. Perhaps most importantly, since many Medicaid enrollees are only covered by the program temporarily, restricting access to a CGT administered on a one-time basis may allow states to shift the cost of the therapy onto future payers, while forfeiting only a portion of its benefits.

Mitigating access restrictions resulting from these and other factors would likely require tools that more directly change states’ options or incentives. These include: (1) requiring states to offer greater access to CGTs, such as by more aggressively enforcing current law coverage requirements; (2) increasing federal subsidies for states’ CGT costs; or (3) reducing the underlying prices of CGTs, such as by requiring manufacturers to pay larger statutory rebates or somehow facilitating broader use of supplemental rebate agreements.

All these approaches could, in principle, expand access, but they also differ in important ways. First, they would have different effects on state and federal costs and manufacturer revenues; simply requiring states to offer greater access would place the highest costs on states, while the latter options would achieve lower state costs by either increasing federal costs or reducing manufacturer revenues. Second, these approaches differ in terms of their feasibility; notably, while federal policymakers likely have tools under current law to compel states to expand access to these therapies (albeit ones they have often been cautious about using in the past), the other approaches would likely require new legislation.

4. If states want to facilitate broad access to CGTs, they will need to take steps to ensure that Medicaid managed care plans’ selection incentives do not undermine that goal.

A substantial majority of Medicaid enrollees now receive their care through Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs). Enrollees can generally choose among multiple MCOs, so an MCO that provides relatively easy access to a particular CGT will tend to attract more patients needing that therapy—and incur correspondingly large costs—likely without meaningfully increasing the MCO’s overall enrollment. Thus, absent mitigating policies, MCOs are likely to have strong incentives to restrict CGT access.

States have a variety of options for addressing these selection incentives. The simplest solution would be to simply carve payment for these therapies out of MCO contracts and manage this spending directly. States could also rely on the standard toolkit for addressing selection problems, including regulating MCOs’ coverage policies related to CGTs or changing MCOs’ financial incentives through risk adjustment or reinsurance.

________

In sum, there are good reasons to suspect that Medicaid enrollees will often face restrictions on their ability to access CGTs. While outcome-based and perhaps especially annuity payment models may help expand access in some cases, they will not address some key drivers of access restrictions. Thus, if the goal is to ensure broad access to these therapies in Medicaid, federal policymakers will likely need to draw on a more basic toolkit—mandating coverage, subsidizing coverage, or reducing underlying prices—while states will need to take steps to mitigate Medicaid MCOs’ risk selection incentives. These tools may also be relevant beyond Medicaid. While private payers are usually less restrictive than Medicaid, selection incentives and incentives to shift costs onto future payers could create parallel access problems in some private insurance markets.

The remainder of this analysis examines these points in greater detail.

Background on cell and gene therapies and the Medicaid policy landscape

Cell and gene therapies (CGTs) are a broad class of therapies that use living cells or genetic material to treat disease. These therapies often aim to address the underlying causes of diseases at a molecular or cellular level. This section provides a brief introduction to these therapies and then discusses how Medicaid’s existing payment and coverage rules are likely to apply to them.

What are gene therapies?

Gene therapies aim to replace or compensate for malfunctioning or missing genes or to edit or disable problematic genes. These therapies hold potential to treat—and in some cases cure—genetic diseases by precisely targeting the underlying genetic abnormalities. This strategy can often be particularly effective for disorders caused by a mutation in a single gene.

Some therapies introduce new DNA into cells or modify existing DNA. Others introduce RNA into cells to affect gene expression or protein production. While many DNA therapies have the potential to deliver long-lasting effects with a single treatment (since DNA is long-lived in cells), RNA therapies must be repeated periodically (since RNA is transient).

What are cell therapies?

Cell therapies introduce cells into the body that perform functions that the body’s existing cells cannot perform. The types of cells used and how they are introduced into the body vary widely across therapies depending on the therapeutic goal. Therapies also differ in whether the cells used are derived from the patient’s own body (“autologous” cells) or whether they are derived from a donor (“allogenic” cells). Cell therapies are not entirely novel; hematopoietic stem-cell transplants (e.g., bone marrow transplants) have been used for decades to treat some types of cancers.

Many new cell therapies involve some degree of genetic modification. A recently approved therapy for beta-thalassemia and two recently approved therapies for sickle cell disease involve extracting a patient’s blood stem cells, genetically modifying them so that they express a needed protein, and reinfusing them back into the patient to produce red blood cells. Another category of cell therapies is Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies, which use a patient’s own immune cells to treat cancer. In CAR-T therapies, T-cells are extracted from the patient’s blood and genetically modified to express chimeric antigen receptors. These receptors enable the T-cells to recognize and attack cancer cells more effectively when they are reinfused into the patient.

How many therapies are currently available, and what is ahead?

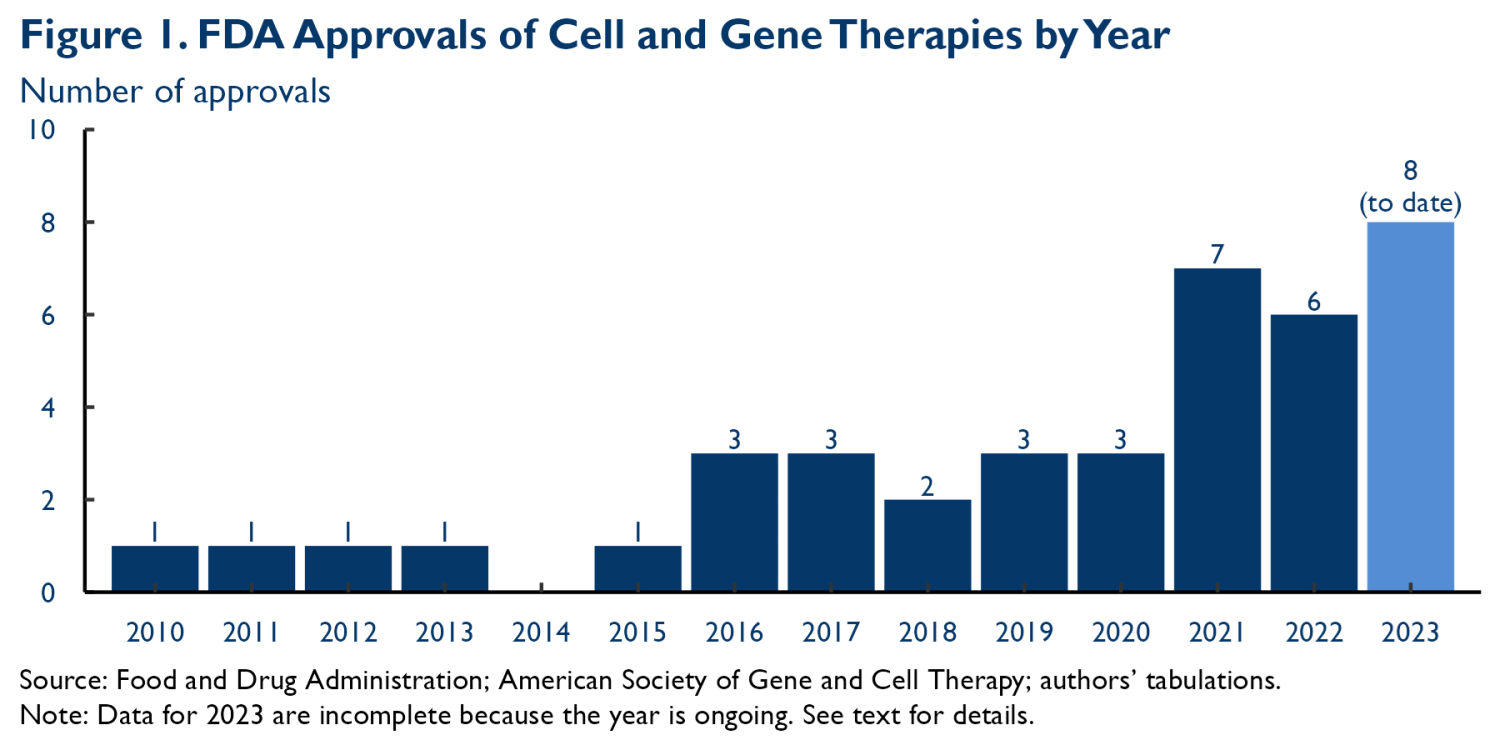

Figure 1 depicts the flow of new CGT approvals by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); there are currently 40 approved therapies, with around two-thirds of those approvals coming in 2019 or later.1 IQVIA reports that more than 700 CGTs were in active development in 2022. These therapies target many different types of conditions. Among therapies in clinical trials, 27% target cancer and 19% target metabolic conditions, but meaningful fractions also target central nervous system, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, ophthalmologic, and other conditions.

What is involved in producing and administering cell and gene therapies?

Many CGTs are challenging to produce, much more so than small molecule drugs or other types of biologics. For example, the viral vectors used to deliver genetic material in some gene therapies are generally produced inside specially engineered cells and then must be harvested and purified before being administered to patients, a complex and resource-intensive process. Extracting and modifying a patient’s cells, as many CGTs require, can also be costly. These manufacturing challenges may be compounded by the fact that many of these therapies target relatively narrow patient populations, which may limit economies of scale in production.

Due to these manufacturing challenges, producing CGTs can be costly, although systematic data is scarce. Some industry sources and observers report that producing a single patient dose of a viral vector gene therapy can cost hundreds of thousands or even more than $1 million, although at least one study of a specific hemophilia B therapy estimated a cost of around $77,000. For CAR-T therapies, production costs of $100,000 to $300,000 per patient have been cited. A caveat is that manufacturing technologies continue to evolve, so current (and future) costs could be lower.

Administering these therapies is also often much more complex than administering traditional drugs. Many therapies require that patients undergo extensive testing to determine their suitability for treatment. Some require the destruction of existing, malfunctioning tissue (e.g., existing bone marrow) prior to treatment, which can involve significant risks and require hospitalization. And patients often require careful monitoring after administration to ensure that the therapy is working as intended and to identify and treat side effects. Institutions that administer CGTs must have the facilities, technologies, and specialized personnel required to deliver this complementary care. The limited size of the populations targeted by some of these therapies may also limit how many facilities incur the necessary fixed costs, limiting geographic availability.

Indeed, only small minorities of providers are equipped to deliver many CGTs.2 This is particularly true for gene therapies. For example, Luxturna (a gene therapy for certain inherited retinal diseases approved in 2017) is administered by only 17 providers in the United States, while Hemgenix (a gene therapy for hemophilia B approved in 2022) is administered by only 16 providers. A larger number of providers have developed the capability to deliver cell therapies. The Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy reports that there are 235 organizations in the United States accredited to deliver at least one cell therapy, although many offer a subset of existing therapies.

What will Medicaid pay for CGTs under current policies?

Many CGTs carry list prices in the hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. Looking across the six CAR-T therapies included in Figure 1 (Abecma, Breyanzi, Carvykti, Kymriah, Tecartus, and Yescarta), list prices ranged from $373,000 to $475,000 at launch. One-time therapies targeting rare genetic conditions often carry even higher list prices. At launch, the list prices of the nine such therapies included in Figure 1 (Casgevy [sickle cell disease], Elevidys [Duchenne muscular dystrophy]; Hemgenix [Hemophilia B]; Lyfgenia [sickle cell disease]; Luxturna [certain inherited retinal conditions]; Roctavian [Hemophilia A]; Skysona [early cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy]; Zyntelgo [beta thalassemia]; and Zolgensma [spinal muscular atrophy]) ranged from $850,000 to $3.5 million for a course of treatment, with all but Luxturna carrying a list price of more than $2 million.

The net prices Medicaid pays will typically be lower than these list prices because federal law generally requires manufacturers to pay rebates on Medicaid utilization, a requirement that will typically apply to CGTs (as long as the state elects to pay for the therapy directly rather than bundling payment with a related service, like an associated inpatient stay). For brand-name drugs, the base rebate is the greater of: (1) 23.1% of the average manufacturer price (AMP), a list price measure; or (2) the difference between AMP and the “best price” that the manufacturer offers to other purchasers (with some exclusions). Drugs that have seen large increases in AMP over time owe additional inflation rebates. States may also negotiate supplemental rebate agreements with manufacturers in which the state encourages greater use of the drug in exchange for a larger rebate, although such rebates accounted for only 9% of all rebates in fiscal year 2022.3

It is uncertain how much rebates will reduce prices in this case. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the net prices that Medicaid paid for a sample of top-selling specialty drugs were 37% of those drugs’ list prices, on average, in 2017. However, there is some reason to believe that rebates could be smaller for these therapies. Notably, production costs will likely be larger relative to CGTs’ list prices than for some other therapies, which may reduce manufacturers’ willingness to offer discounts and thereby reduce rebates under federal “best price” rules or states’ own supplemental rebate agreements. And whatever may be true over these therapies’ full life cycle, net prices will likely be higher relative to list prices in their early years since net prices typically fall relative to list prices over time, a pattern that likely reflects the emergence of competition, among other factors. Medicaid will also need to pay for the complementary services required to deliver these therapies, which will add additional costs. Thus, while the precise cost of these therapies to Medicaid is uncertain, there is little question that the total cost of many such therapies will reach into the hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient or beyond.

Aggregate spending will depend on both unit prices and utilization. Many CGTs, at least so far, target relatively narrow patient populations. For example, the gene therapies listed above mostly target conditions that afflict only tens of thousands of people in the United States, and some of those people may not be good candidates for treatment or may decline treatment due to concerns about a therapy’s side effects or for other reasons.4 Nevertheless, aggregate spending could sometimes be substantial: administering a therapy with a net cost of $1 million per recipient to 25,000 people would cost $25 billion.

The ultimate effect of these therapies on state costs will depend not just on the cost of administering the therapies, but also on how they affect states’ costs of managing the underlying illness. Notably, some CGTs have the potential to generate large offsetting savings by obviating (or lessening) the need for expensive ongoing treatment. Over the long run, these offsetting savings may sometimes even outweigh states’ upfront costs, at least if patients are still covered under Medicaid.

How much discretion will states have to limit access to CGTs, and will they use it?

Federal law generally requires states to cover all FDA-approved drugs when used for a “medically accepted indication.”5 However, states can place some restrictions on that coverage, including prior authorization or step therapy requirements and quantitative utilization limits, within statutory bounds. As a practical matter, the statutory bounds on what restrictions states can impose are likely imperfectly enforced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), so states likely have some ability to go beyond them in practice.

The fact that CGTs typically must be delivered in conjunction with other, complementary health care services may give states additional options to restrict access if they want to. First, if a state elects to pay for a CGT as part of a broader bundle that includes some complementary services, then the federal rules that generally govern drug coverage may not apply, and states may be able to limit coverage more tightly than would otherwise be allowed. (States taking this approach would have to forgo the rebates that manufacturers are generally required to pay, so this approach may only be attractive to states that intend to restrict access very tightly.) Second, states may be able to restrict access to complementary services and, in turn, restrict access to CGTs themselves, such as by placing tight utilization controls on the complementary services or setting very low payment rates. Because many CGTs are delivered by relatively few providers, decisions related to complementary services may be especially important. Many enrollees will need to travel long distances to obtain these therapies, and while states are generally required to cover non-emergency medical transportation, they have considerable discretion in crafting those benefits. In addition, states commonly pay out-of-state providers less than their in-state peers, a policy that may have particularly large effects on access to CGTs where only out-of-state providers are available.

The rest of this analysis considers what factors might (or might not) lead states to make use of their discretion to limit access to CGTs. As context, however, we note that state Medicaid programs are, in general, relatively restrictive payers. State Medicaid programs apply more drug utilization controls than other payers, which likely makes it more difficult to access some medications in Medicaid than in other forms of coverage (notwithstanding the nominal requirement in Medicaid to cover all FDA-approved drugs). Looking beyond drugs, Medicaid programs generally pay lower prices for physician services than Medicare or private insurers. This, together with higher claim denial rates and other administrative burdens in Medicaid, are likely a major reason that physicians accept Medicaid at lower rates than they accept Medicare or private insurance.

States’ responses to the emergence of direct-acting antiviral drugs for Hepatitis C starting in 2013 may presage how they will approach CGTs. These drugs offered a functional cure for Hepatitis C, but at a substantial cost; the first drug to market, Sovaldi, launched with a list price of $84,000 for a course of treatment (a sizeable sum, but still smaller by an order of magnitude than the list prices of many CGTs). States implemented stringent restrictions. Notably, most states restricted treatment to patients who were already experiencing serious liver damage, and states frequently excluded coverage for many patients who used drugs or alcohol. CMS issued guidance in 2015 expressing concern that many such restrictions violated federal law, and there was a wave of beneficiary litigation challenging some state restrictions. While these types of restrictions are now relatively rare, many states maintained them for a considerable period, an indication of the limits of CMS’ willingness or ability to enforce these types of rules. Much of this liberalization may also have resulted from lower prices due to greater competition, not stronger enforcement.

Experience with CGTs themselves is still relatively limited, but there are indications that states’ general enthusiasm for utilization controls extends to CGTs. A study of two CAR-T therapies (Kymriah and Yescarta) and one gene therapy (Luxturna) found, perhaps unsurprisingly, that states commonly apply prior authorization requirements to these therapies. Another study of three therapies (Kymriah, Luxturna, and Zolgensma) found evidence that many states were failing to cover these therapies to the full scope of their FDA approval, such as by only covering patients that fall within the population studied in clinical trials instead of the broader population for which the therapy was approved by the FDA. That could, in principle, go beyond what states are permitted to do under federal law. Another found that some states were applying restrictions to the coverage of CAR-T that a panel of clinical experts assessed to be “unreasonable.”

States’ interest in policies that restrict access to care likely stem in large part from states’ desire to limit their Medicaid costs. Medicaid has, in recent years, consumed around one-fifth of state general fund budgets, on average, even though the federal government picks up around two-thirds of program costs. States may assess that these savings outweigh the forgone benefits to enrollees.

Uncertainty and outcome-based payment models

One of the payment approaches being considered by CMMI is adopting outcome-based payment models that link payment to realized clinical outcomes. CMMI has floated three closely related approaches that differ only in when manufacturers are paid: under the first, manufacturers would receive an upfront payment plus a later supplemental payment if patient outcomes meet a specified standard; under the second, manufacturers would receive an upfront payment (that would, presumably, be larger than the under the first approach) and be required to pay a rebate if patient outcomes did not meet the standard; and under the third, manufacturers would receive a steady stream of payments (an “annuity”) for as long as patient outcomes continued to meet the standard. CMMI envisions that it would negotiate and operate these models on states’ behalf.

Outcome-based payment arrangements only differ from traditional payment arrangements to the extent that there is uncertainty about how a new therapy is likely to perform, so we begin this section by considering what may be uncertain about CGTs and where this uncertainty may come from. We then consider how outcome-based payment might (or might not) encourage states to expand access to CGTs as well as the tradeoffs involved.

What is uncertain and why?

Any new therapy comes with some uncertainty about its clinical benefits and related effects (e.g., downstream cost savings from improved health or reduced need for alternative treatments). But there are reasons that uncertainty may be greater for some CGTs than for other therapies. Indeed, this uncertainty is one feature of CGTs highlighted by both CMMI and other observers in discussing the challenges posed by CGTs and the rationale for alternative payment approaches.

First, CGTs generally rely on novel technologies and biological mechanisms. This may make it harder for trial designers to know what to look for when designing trials, for example with respect to side effects or variation in a therapy’s effects across different types of patients. As a result, trial evidence may be somewhat less informative than it would be for better-established categories of therapies. A lack of experience with similar therapies may also make extrapolating from trial evidence to real-world clinical practice a more uncertain endeavor.

Second, many CGTs are administered once or a small number of times but are expected to generate long-lasting clinical benefits. There are also theoretical scenarios in which some such therapies could produce major side effects that emerge long after administration. But to avoid long delays in making therapies available to patients, the FDA has often (appropriately) approved these therapies based on data for a relatively short period following administration. For example, the clinical data that FDA relied on when approving several new therapies targeting genetic conditions (Hemgenix, Skysona, and Zolgensma) extended two years or less after administration. In practice, there is often a reasonable biological basis for expecting benefits to be persistent. The FDA has also issued guidance indicating that it will require manufacturers of some types of gene therapies to follow trial participants for up to 15 years after administration (driven in large part by concerns about delayed side effects). Nevertheless, states may still face greater-than-usual uncertainty about these therapies’ long-term safety and effectiveness profiles, particularly initially.

Third, some CGTs target relatively rare conditions, which creates challenges in recruiting trial participants. As a result, some therapies may be approved based on trials with relatively small sample sizes and, thus, relatively imprecise estimates of the therapy’s effects. The FDA has also been open to trials without a randomized control group for such therapies, which can also add uncertainty about these therapies’ effects, at least to the extent that the course of the disease in the absence of treatment is not well understood. Indeed, several recently approved therapies targeting genetic conditions have been approved without data from randomized controlled trials.

How might (or might not) outcome-based payment affect coverage decisions?

Under an outcome-based payment arrangement, a state pays more when a therapy turns out to perform well and less when it performs poorly. This differs from traditional arrangements, where the state pays the same amount regardless of how a therapy ultimately performs.

It is far from obvious, however, that this difference can facilitate greater access to CGTs. What should matter to a (rational) state deciding whether and how to cover a therapy is the expected costs it would incur, relative to the expected benefits, averaged across all scenarios for how the therapy might perform. Thus, to entice a state to offer more robust access, an outcome-based arrangement generally must reduce the state’s expected costs.6 But, as long as the state and manufacturer have similar expectations about how a therapy is likely to perform, any outcome-based arrangement that reduces the state’s expected costs will also commensurately reduce the manufacturer’s expected revenues. Since CMMI seems to envision that outcome-based arrangements would be voluntary for manufacturers,7 it follows that arrangements attractive enough to encourage states to expand access would fail to elicit participation from manufacturers.

There are caveats to this pessimistic view. One arises if a manufacturer holds information that is not available to states (e.g., because the manufacturer better understands the underlying science or has better access to clinical trial data) and that information suggests a therapy is likely to perform better than the state believes it will perform. In principle, a manufacturer might seek to encourage states to cover the therapy by sharing this information directly, but it will often be hard for manufacturers to communicate this type of information in a credible fashion (since it is always in a manufacturer’s interest to say that its products are highly effective and very safe).

In this case, an outcome-based contract can offer a solution. A contract that specifies a lower price if the therapy performs as the state expects and higher price if the therapy performs as the manufacturer expects may induce the state to allow broader access (provided that the amounts the state must pay in all scenarios are commensurate with the value it places on those therapeutic outcomes). And the manufacturer will be willing to accept such a contract precisely because it expects the therapy to perform well and thus receive the higher price. In effect, the outcome-based contract works by letting the manufacturer “put its money where its mouth is.”

Another caveat is that states may care about more than just expected costs and benefits. Notably, policymakers may worry about being criticized for spending money on a therapy that turns out to be ineffective or have severe side effects. Outcome-based payment can mitigate this risk by reducing what a state owes if a therapy performs poorly, which may make states more willing to allow robust access even if the outcome-based arrangement does not reduce expected costs. On the other hand, adopting an outcome-based arrangement could also expose policymakers to criticism that they paid more than necessary if a therapy turns out to be highly effective and the state owes more than it would have under a more traditional arrangement; this possibility may reduce the appeal of outcome-based arrangements and, thus, their ability to expand access.

Related, outcome-based arrangements are sometimes described as a tool for reducing the amount of financial risk states bear. This may be true to some degree for therapies that have the potential to reduce the need for other types of costly treatment. In such cases, an appropriately crafted outcome-based contract can help insulate the state against the resulting financial risk by allowing the state to pay less for the therapy when cost savings do not materialize and more when they do materialize. In general, however, offloading financial risk is valuable only when the risk is large relative to the financial resources an entity possesses.8 Most of these risks are likely small relative to states’ Medicaid budgets and, particularly, relative to states’ overall budgets, which suggests that the value of this risk protection is also small. (Moreover, where the uncertainty is principally about whether a therapy will generate the promised health benefits, an outcome-based contract can actually increase how much financial risk states bear since it links the state’s future cash flow to the therapy’s uncertain performance.)

Tradeoffs with outcome-based payment

While outcome-based arrangements could sometimes expand access, they would also have other effects that policymakers may view as less desirable. Importantly, these other effects will often arise even when outcome-based payment does not expand access, which suggests that policymakers may want to be judicious in where and how they deploy these payment models.

First, these approaches are very likely to increase states’ payments to manufacturers. Consistent with the discussion above, a manufacturer will presumably only agree to an outcome-based arrangement if it expects to earn larger profits than it would earn under Medicaid’s usual payment and coverage rules (given the outcomes it expects to achieve), which will typically mean higher program spending.9 That may be particularly likely if manufacturers have private information about therapies’ likely performance since manufacturers will be disproportionately likely to agree to such contracts in cases where they believe a therapy is highly effective. Manufacturers are also likely to demand some risk premium for bearing the financial risk these models involve.10

Second, administering these types of arrangements is likely to be complex. Implementing an outcome-based arrangement requires determining what outcome measures will be used, defining what standard must be met, and setting up an administrative apparatus for measuring those outcomes. Paradoxically, making these decisions may be more difficult for CGTs that it would be for other types of therapies given the limited experience with these therapies and the uncertainty about their effects. Measurement may also be challenging given that it is likely to require ongoing cooperation from patients or their providers, including after patients leave Medicaid for other forms of coverage. These activities are likely to involve significant administrative costs and, for therapies targeted at relatively small patient populations, may be cost-prohibitive. CMMI’s proposal to administer these contracts on a multi-state basis may ameliorate this concern by unlocking some economies of scale, but the relevant costs may still be sizeable.

Short-term budgetary frictions, policymaker myopia, and annuity payment models

One of the outcome-based payment models CMMI is considering has a distinctive feature: the manufacturer would be paid, at least in part, through a stream of annuity payments, rather than through one or two lump sum payments. In this section, we consider what problems an annuity payment structure can solve, whether in isolation or as part of an outcome-based model.

Broadly, annuity payment could help expand access if spreading payment over time made a therapy’s costs easier or more appealing to bear—and this effect outweighed the increase in the total amount of payment that manufacturers would demand in return for delaying payment.11 One way that spreading payments over time might make a therapy’s costs easier to bear is by smoothing state costs. Some CGTs, particularly some gene therapies, target a stock of patients with chronic disease and are administered on a one-time basis. That means that the costs associated with these therapies may appear suddenly when the therapy comes to market and then fade as the stock of patients with the condition is depleted. In the case of therapies with sizeable eligible populations, this spike in spending could be large relative to state Medicaid budgets, which could make them difficult for states to accommodate, especially since states (unlike the federal government) generally must balance their budgets annually.12 These types of short-term budgetary frictions could lead states to impose access restrictions on CGTs, at least for some period following their introduction. By smoothing payment over time, annuity payment models could help prevent this.

The smoothing difficulties that states may face should not be overstated. Consider the earlier example of a therapy priced at $1 million per person treated that is administered to 25,000 people. If one-third are covered by Medicaid, this would generate Medicaid spending of $8 billion. If an expense that large were incurred in 2023, it would increase Medicaid spending by around 1% (and states’ overall spending, including both Medicaid and non-Medicaid spending, by much less).13 In practice, provider and manufacturer capacity constraints, as well as other factors, would cause the additional spending associated with the new therapy to be spread over multiple years, so the actual effect would likely be much less than one percent in any year. Indeed, a study examining a potential cure for sickle cell disease, a relatively common genetic disease, concluded that covering the therapy would increase Medicaid spending in the first year by 0.1% nationwide and 0.4% in the most exposed states. States likely routinely encounter year-to-year fluctuations in spending that are larger than this. To be clear, these costs are not trivial, and, as we discuss in the next section, they may still be large enough to spur states to impose access restrictions, but it is unclear that the timing of these costs will be the main problem. Nevertheless, the emergence of a therapy where smoothing would be a major concern cannot be entirely dismissed.

Another—and perhaps more important—reason that spreading payment over time might help expand access is that state policymakers may be myopic; that is, they may place a heavy weight on near-term costs relative to costs that would be incurred in future years, perhaps because election and budgetary cycles promote a focus on relatively short time horizons. If this is the case, then allowing states to shift costs into the future could lead them to allow broader access. This effect could be relevant even for therapies with relatively low aggregate costs where smoothing is not a major concern.

This effect could be especially important for therapies that generate large offsetting cost savings by reducing the ongoing cost of managing the treated condition. In those cases, annuity payment can align a therapy’s costs and benefits more closely in time, potentially transforming a therapy with large near-term costs into one with only modest near-term net costs or possibly, in some cases, near-term cost savings. For policymakers with short time horizons, that change in the timing of a therapy’s costs and benefits may have an important effect on the therapy’s attractiveness.

Notably, while spreading payments over time could reduce the burden of those payments to states, it would likely increase the total amount states owed since manufacturers would demand compensation for, in effect, making a loan to the state. Thus, whether adopting annuity payment would make covering a therapy more attractive on net would depend on the implicit interest rates manufacturers demanded. Because payments under an annuity contract would be a claim on state and federal governments, manufacturers might accept rates close to typical government borrowing rates, which are generally moderate; yields on 10-year federal government bonds are currently projected to be around 4% over the next decade. If manufacturers demanded higher rates (e.g., because they had to finance delayed payments at their own, typically higher borrowing rates), federal policymakers could explore whether they could pay manufacturers up front and then collect from states over time.

The annuity payment model proposed by CMMI would be complex to administer because it would link annuity payments to outcomes. However, linking payments to outcomes is not necessary to achieve the potential access benefits of annuity models discussed in this section. Annuity payment models without an outcome-based component would likely be straightforward to administer since states would merely need to ensure that pre-specified payments were made on schedule.

Other drivers of access restrictions and potential policy responses

If states implement stringent access restrictions on CGTs, we suspect that uncertainty about CGTs’ effects (the issue targeted by outcome-based payment models) or short-run budgetary frictions (the issue targeted by annuity-based payment models) will not be the main drivers. This section examines other factors that may play a larger role in driving states to place access restrictions on CGTs and then discusses how policymakers might address these other factors.

Other potential factors driving access restrictions

The forces that shape states’ decisions related to CGTs will likely be largely similar to the forces that shape their decisions about other types of care—and that have made Medicaid a relatively restrictive payer across many different domains. One central factor is that public funds are a scarce resource, and a dollar devoted to Medicaid must either be collected in taxes or diverted from other program areas. This likely often leads states to place a high weight on limiting program costs relative to delivering benefits to Medicaid enrollees, leading to access restrictions.

There are, however, features of CGTs that could cause states to be more inclined to restrict access to these therapies than to other types of health care:

- Scope to shift costs to other payers: Some emerging CGTs, notably some therapies targeting genetic conditions, would be administered on a one-time basis and generate benefits that extend well into the future. Furthermore, in at least some cases, delaying treatment may forfeit only a relatively small portion of those benefits. In particular, while patients would continue to suffer from the targeted condition during the delay—and some may experience complications that have long-term consequences—they may still realize most or all of the long-term benefits of treatment once they are finally treated.

This matters because many Medicaid enrollees are covered by the program temporarily. Thus, restricting access to these types of therapies could sometimes allow states to shift the cost of treatment onto a future payer while depriving patients of only a portion of the benefits of the treatment.14 This could make restricting access to these therapies particularly attractive relative to other types of care (e.g., emergency care), where deferring care often means forgoing virtually all the potential benefits of that care. A caveat is that enrollees who are good candidates for CGTs may, on average, have longer enrollment durations than the Medicaid enrollees overall, which may temper the benefits of delay to some degree.15

- Reduced salience due to concentrated benefits: Because CGTs have large costs and benefits per person who receives them, the number of people who benefit is small relative to the aggregate costs and benefits involved. This might make the benefits of these therapies less politically salient and thus reduce what states are willing to pay. (On the other hand, the concentration of benefits in a small population could also catalyze more intensive advocacy activity, which could work in the opposite direction.)

- Greater reliance on out-of-state providers: As noted above, many CGTs are administered by a relatively small number of providers due to the specialized clinical capabilities required, so many states may have to rely heavily on out-of-state providers if they want to ensure access to these therapies. Providers may often be an important constituency for more robust Medicaid coverage, but out-of-state providers may be less able to play this role than their in-state counterparts. The fact that states generally pay out-of-state hospitals less than they pay in-state hospitals for the same services is consistent with this theory.

A final factor worth considering is that many utilization management tools (notably, prior authorization) involve costly case-by-case determinations and, thus, may make most sense to use when per case costs are large.16 Thus, if states’ willingness to pay for CGTs is low relative to these therapies’ costs, whether for reasons specific to CGTs or for other reasons, CGTs’ high per case costs may make states particularly likely to react by implementing access restrictions.

Policy options for expanding access

If federal policymakers want to prevent states from restricting access to these therapies, they will likely need to consider approaches that change states’ underlying options or incentives. Broadly, the main potential approaches are: (1) requiring states to meet higher access standards with respect to CGTs; (2) increasing federal subsidies for coverage of CGTs; or (3) reducing CGTs’ underlying prices. Below, we describe each of these options and then briefly compare them.

Require states to meet higher access standards. One approach to expanding access to CGTs would be for CMS to more aggressively enforce states’ obligations to cover all FDA-approved therapies in Medicaid. It is unclear to us to what extent states will implement restrictions that go beyond what federal law allows, although the early reports on the types of restrictions state Medicaid programs have placed on CGTs discussed above, as well as the experience with other expensive therapies like the direct-acting antivirals for Hepatitis C suggest that it is plausible that states will sometimes implement restrictions on these therapies that go beyond what federal law allows. Congress could also, of course, choose to implement more stringent standards.

Increase federal subsidies. Another way to encourage states to expand access would be for the federal government to pick up a larger share of the cost of CGTs. In most cases, offering more generous federal support to state Medicaid programs would require legislative action.

However, perhaps particularly for one-time therapies, it might sometimes be possible to make progress administratively with creative use of waiver authority. In general, a prerequisite for a waiver approach to be viable would be demonstrating that the increase in federal spending in Medicaid (accounting for the new federal subsidies and the cost of any resulting increase in utilization, but also any offsetting savings from reduced costs of treating the underlying condition) was more than offset by reductions in spending elsewhere in the federal budget. Under CMMI’s waiver authority, these offsetting savings would need to accrue in Medicare. Under current policy, Medicaid’s section 1115 waiver authority could likely not be used in this way since savings outside of Medicaid are generally not counted in assessing whether a waiver meets CMS’ “budget neutrality” requirements; however, CMS has considerable discretion in establishing budget neutrality rules and might be able to count a broader array of federal savings if it wished.

A key question, then, is how likely offsetting savings are in practice. It is very likely that expanding access to CGTs in Medicaid would generate some savings in other part of the federal budget. Specifically, greater utilization in Medicaid would often relieve future payers of the cost of paying for the therapy for the affected enrollees and, potentially, reduce costs further by improving enrollees’ health. Because the federal government subsidizes nearly all forms of insurance coverage (Medicare directly and private insurance via the tax exclusion for employer-provided coverage and the premium tax credit), a substantial portion of these savings to those other payers would ultimately accrue to the federal government. In some cases, treatment could also improve recipients’ ability to work, which could increase federal revenues or reduce benefit costs (although it could also increase longevity, which might increase Social Security or Medicare spending).

Net savings, however, would likely be rarer. The likelihood of net savings would depend on a variety of factors, including the likelihood that people who newly received the therapy in Medicaid would otherwise have received it from another payer and how the prices Medicaid paid for that therapy compared to the prices paid in other forms of coverage. It would also depend on the design of any subsidy increase, particularly whether new subsidies could be limited to incremental utilization (e.g., by making payments only for utilization above some projected baseline level) or to people particularly likely to transition to other payers (e.g., people approaching age 65).

Reduce prices. A final strategy for expanding access would be to reduce the prices of CGTs.

One way policymakers could do this is to facilitate greater use of supplemental rebate agreements focused on reducing the level of payment (rather than the changing the structure of payment, the focus of CMMI’s proposed models). Indeed, this is how supplemental rebate agreements are traditionally used: states offer greater access to a manufacturer’s therapy in exchange for the manufacturer agreeing to pay rebates above the statutorily required level.17

In principle, there is real potential to expand access to CGTs through these types of agreements. A manufacturer should be willing to accept an agreement under which it is paid the same amount as it would be without an agreement plus an amount adequate to cover its marginal costs on the incremental utilization enabled by an agreement; such an agreement would (weakly) increase the manufacturer’s profits. At the same time, the resulting price on the incremental utilization may often be low enough to make it attractive to the state to expand access on those terms. A caveat is that this may be less true for CGTs than for other therapies given their relatively high production costs, which may create more scenarios where even pricing the incremental utilization at the manufacturer’s marginal cost may still result in a price above a state’s willingness to pay.

In practice, there may be several important barriers to greater use of these type of arrangements. First, negotiating these types of agreements may be burdensome for states and manufacturers, which may reduce how often they are worth pursuing. Second, manufacturers may be reluctant to offer price concessions because they expect states to eventually relent and expand access even in the absence of an agreement or because they fear that offering concessions to one state will lead other states to seek similar concessions. Third, for therapies administered on a one-time basis, manufacturers may sometimes actually benefit from access restrictions in Medicaid since it may increase future use of their product in forms of coverage where they are paid higher prices; thus, they may be reluctant to engage in negotiations aimed at reducing those access restrictions.

The latter two barriers to greater use of these agreements may be largely intractable, but it is conceivable that CMS could play some role in making negotiating these agreements easier. CMS could negotiate agreements at the federal level and then allow states to join, as CMMI is proposing for its outcome-based models. Centralizing negotiation and administration of these types of agreements could, in principle, unlock economies of scale that make them more viable. However, in light of the fact that states already sometimes band together to negotiate supplemental rebate agreements, yet supplemental rebate agreements still play only a modest role in Medicaid, there is reason to question whether further centralization would have large effects.18

Even if expanding use of supplemental rebates is not viable, policymakers could reduce prices by increasing the mandatory rebates required under the Medicaid drug rebate program. However, unlike trying to increase use of supplemental rebate agreements, this strategy would likely require legislative action. This strategy also could not reduce net prices below manufacturers’ production costs, at least without spurring manufacturers to try to stop supplying their therapies to Medicaid enrollees; as noted above, this may be a more relevant constraint for CGTs than other therapies.

Comparing these three approaches. All these approaches could increase access to CGTs in Medicaid, at least to some degree. There are, however, important differences.

First, they would have different effects on federal spending, state spending, and manufacturer revenues, even for a given change in utilization. In general, requiring states to provide greater access would increase federal spending, state spending, and manufacturer revenues relative to the status quo. Offering more generous federal subsidies would magnify the increase in federal spending and dampen (or potentially even reverse) the increase in state spending, while reducing prices would lead to smaller increases in both state and federal spending and smaller increases (and perhaps outright decreases) in manufacturer revenue. The choice among these approaches would, thus, depend on how policymakers’ weighed increases in state versus federal spending, as well as how they viewed tradeoffs between higher public spending and higher manufacturer revenues, including any potential effects on incentives to develop new therapies.

Second, the three approaches may differ in feasibility. Stepping up enforcement of states’ existing obligations to cover FDA-approved therapies could, in principle, substantially improve access through administrative action alone, whereas the other approaches would likely require new legislation. On the other hand, this strategy requires CMS to take enforcement action against states that fail to meet their obligations, which may be challenging in practice. Indeed, CMS’ relatively cautious approach in confronting the restrictions states imposed on access to direct-acting antivirals for Hepatitis C offers some reason for pessimism about this strategy. If that pessimism is warranted, then the legislative pathways may be the only viable options.

Selection problems in Medicaid managed care

Even if states wish to ensure broad access to CGTs, achieving that outcome will require careful attention to the incentives of Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs). MCOs are now responsible for delivering Medicaid benefits to the large majority of Medicaid enrollees.

The core challenge is adverse selection. Enrollees will generally know whether they have a condition potentially treatable by a CGT, particularly in the case of therapies targeting genetic conditions. Thus, patients who need a particular CGT are likely to gravitate toward MCOs that make it easier to access that therapy, while patients who do not will likely place little weight on the relevant MCO policies when choosing an MCO. As a result, absent mitigating policies, MCOs who offer less restrictive coverage for CGTs are likely to attract many enrollees who need these therapies and incur correspondingly high costs, but without meaningfully increasing their total enrollment. MCOs will thus have strong incentives to create barriers to accessing CGTs.

There are variety of options for coping with this problem. One simple and straightforward approach would be to carve these therapies out of managed care contracts; that is, a state could pay for these therapies and manage the associated care directly rather than through its MCO contracts. This has often been done with mental health and substance misuse services and some types of care for people with disabilities. That approach could fully resolve selection-related access problems. It would put the onus on the state to ensure that CGT-related care is managed efficiently, although this might be more straightforward than in other settings since many of these therapies have relatively clearly defined indications, so overuse might not be a major concern.

If states elected to keep CGTs within MCOs’ purview, they could instead draw on the standard toolkit for addressing selection problems in health insurance markets:

- Benefit regulation: One approach is to directly regulate the level of access MCOs provide. The viability of this approach would depend on how effectively states could monitor MCOs’ coverage policies, which could be challenging to do well in practice.

- Risk adjustment: Another, potentially complementary, approach is to remove MCOs’ financial incentive to avoid patients who need CGTs through risk adjustment, which aims to align payments to plans with enrollees’ claims risk. Making risk adjustment effective in this setting would require overcoming at least two important types of challenges.

First, risk adjustment models would need to keep pace with the changing treatment landscape. Risk adjustment models are typically calibrated using regression analyses of historical spending data. But the costs of CGTs will not be reflected in the data used for calibration until they have been available for some period of time (likely at least a couple of years), during which time risk adjustment would not address selection incentives. Moreover, those incentives could persist over the long-term if MCOs respond to inadequate risk adjustment in the short-run by restricting access, and risk adjustment models are subsequently calibrated using data that reflect the resulting low utilization.

Second, risk adjustment models might need to be modified to allow them to appropriately distinguish enrollees who are and are not candidates for a particular CGT. This could sometimes cause calibration challenges since some CGTs target small populations, which could cause the samples available for calibration to be small in practice.

- Reinsurance: Another approach to mitigating MCOs’ incentives to avoid patients who need CGTs is to compensate MCOs for all or part of the costs of administering these therapies, a form of reinsurance. (This type of reinsurance, which aims to offset part of the costs of a particular type of care, differs from reinsurance mechanisms that operate in Medicare Part D and the individual and small group markets, which aim to offset part of the cost of any enrollee with high spending, regardless of the source of that spending.)

In structuring this type of approach, policymakers would face a tradeoff. If reinsurance payments compensated MCOs for less than the full amount of these costs, then MCOs would retain some incentives to avoid enrollees who need these therapies. On the other hand, if reinsurance payments fully compensated MCOs for the costs they incurred, then MCOs would have no incentive to manage those costs at all. In many respects, full reinsurance would be similar to the carveout approach discussed above, except that the state might be in a worse position to manage these costs since the MCO would remain notionally responsible for that care; if overuse turns out not to be a major concern with respect to many of these therapies, as conjectured above, then this downside of full (or near-full) reinsurance relative to the carve-out approach might be relatively small.

In practice, many approaches to managing selection incentives could work, but the carveout approach would likely be the easiest to implement, as it would be familiar to states and require neither the extensive monitoring of MCO policies needed under the benefit regulation approach nor the detailed cost data needed for the risk adjustment approach. States could also use a combination of approaches. For example, a state could carve these therapies out of their MCO contracts initially and then rely on a combination of benefit regulation and risk adjustment after the data needed to appropriately calibrate risk adjustment models became available.

Conclusion

Under current policies, Medicaid enrollees will likely face challenges in accessing CGTs. Medicaid has a long history of stringent utilization controls driven by states’ desire to contain program costs, and specific features of some CGTs, particularly states’ ability to shift costs to other payers by delaying treatment, may make restricting access to these therapies particularly attractive. Medicaid MCOs’ risk selection incentives will add to these challenges.

While outcome-based and perhaps especially annuity payment models may help expand access to some degree, the problems targeted by these approaches (uncertainty in the case of outcome-based models and short-term budgetary frictions or policymaker myopia in the case of annuity models) are unlikely to be the only, or perhaps even the primary, drivers of access restrictions. Rather, if federal policymakers want to ensure broad access to these therapies in Medicaid, they will likely need to rely on a more basic toolkit: mandating coverage, subsidizing coverage, or reducing underlying prices. Ensuring broad access will also require state policymakers to take steps to mitigate Medicaid MCOs’ selection incentives, whether by carving these therapies out of managed care contracts or through policies that directly counter selection incentives.

In closing, we note that Medicaid will not be the only payer grappling with whether and how to cover CGTs.19 In general, other payers tend to impose fewer utilization restrictions than Medicaid does. However, private payers may be more inclined to impose restrictions on CGTs than for other types of care given the potential to shift costs onto other payers and the potentially strong selection incentives in this setting. Selection may be particularly important in markets where consumers choose plans individually, like the individual market and the Medicare Advantage market. To the extent that access problems do arise in private insurance markets, the toolkit available for addressing those problems is likely to broadly resemble the toolkit available in Medicaid.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

We thank Loren Adler and Edwin Park for helpful comments and conversations, Paris Rich Bingham and Julia Paris for excellent research assistance, and Caitlin Rowley for excellent editorial assistance. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Arnold Ventures. All errors are our own.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- For these purposes, we include products listed by the FDA’s Office of Tissues and Advanced Therapies (excluding cord blood therapies and Wilate) as of December 7, 2023, plus two therapies for sickle cell disease approved on December 8, 2023, as well as non-vaccine RNA therapies listed in an October 2023 report by the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy that are approved in the United States. We obtain approval dates from the FDA Orange Book or Purple Book, as relevant.

- Provider counts in this paragraph were current as of November 16, 2023.

- This estimate was calculated from Medicaid financial management report data.

- Prevalence estimates for these conditions were obtained from MedlinePlus.

- Technically, states may avoid these requirements if they decline to offer any prescription drug coverage, but all state Medicaid programs currently offer prescription drug coverage.

- Depending on the circumstances, the best available alternative payment arrangement may be Medicaid’s base payment rules or a non-outcome-based supplemental rebate agreement.

- It is not clear whether CMMI could allow states to implement outcome-based payment arrangements on a mandatory basis. Since this would involve declining to cover a drug unless the manufacturer agreed to a suitable outcome-based arrangement, it would require waiving the requirement to cover all FDA-approved drugs that appears in section 1927 of the Social Security Act. The waiver authority available to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation under section 1115A of the Social Security Act likely cannot be used in this way. Whether CMS can use the Medicaid waiver authority under section 1115 of the Social Security Act for this purpose is controversial.

- Offloading a small risk may be valuable if it is correlated with other, larger financial risks an entity faces, but that is likely not the case here.

- An exception could arise if implementation of an outcome-based arrangement led to lower utilization, for example because it led manufacturers to discourage utilization by patients of marginal appropriateness. In this case, an outcome-based arrangement could both reduce states’ spending and increase manufacturers’ profits to the extent that it reduced manufacturers’ production costs. But this scenario seems unlikely in practice.

- Unlike for states, the financial risk associated with the success or failure of a particular therapy may be large for the therapy’s manufacturer.

- One of the other outcome-based models CMMI is considering would also spread payment over time by having states make a partial upfront payment and then a subsequent payment if specified clinical outcomes were achieved. Any effects on state decisions would likely be much smaller than under a true annuity approach, however. Additionally, the model that envisions an upfront payment followed by an outcome-contingent rebate from the manufacturer would tend to concentrate payment upfront and, thus, could work in the opposite direction.

- A technical panel convened by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission highlighted another type of budgeting challenge: for CGTs that treat rare conditions, the number of people requiring treatment may be small and, correspondingly, vary widely from year to year (measured as a fraction of typical annual utilization). While this is true, the low absolute level of utilization in this scenario implies that aggregate spending on these therapies would be small relative to state Medicaid budgets even in the years where utilization is higher than normal. Thus, we suspect that this type of variability would be relatively easy for states to accommodate.

- This calculation reflects the most recent National Health Expenditure projections.

- A key assumption is that state policymakers care principally about the state’s costs and disregard potential savings to the future payer. There are reasonable arguments that states should not behave in this way, but it is plausible that states do behave this way in practice, at least to some degree.

- For example, some therapies may typically be administered to children (who are eligible for Medicaid over a broader range of incomes), to people who are often unable to work because of their condition (and thus experience little income volatility), or to people who qualify for Medicaid through pathways (e.g., medically needy pathways) for which short-term income fluctuations may have less effect on eligibility.

- While we suspect that the greater feasibility of utilization management tools for high-cost therapies usually results in more restrictive access, the opposite could be true in some cases. For example, if a state believes that the benefits of treatment exceed the cost for some patients but not others, it might adopt costly processes designed to distinguish the two types of patients when per case costs and benefits are large but adopt blunter restrictions otherwise.

- These agreements have occasionally taken the form of “subscription models” under which the state makes an upfront payment to the manufacturer but can access additional doses at a low (or zero) cost, an approach that some have proposed using in the context of CGTs. But regardless of the specifics of the contract structure, the basic effect is similar: the manufacturer receives additional volume, while the state receives a lower price per unit. These structures do differ in states’ and manufacturers’ incentives to encourage utilization at the margin, which may matter if it is difficult to directly contract on states’ utilization controls or manufacturers’ promotional activities.

- Some of the other policies considered in this analysis could, in principle, also affect states’ ability to negotiate lower prices through supplemental rebate agreements. For example, if outcome-based or annuity payment makes the cost of CGTs easier or more attractive to bear, that could make it harder for states to credibly threaten to restrict access and thereby reduce their leverage to negotiate supplemental rebates. Imposing stronger access standards or expanding federal subsidies could, in principle, have similar effects. In practice, the scope to “crowd out” existing supplemental rebate agreements may be small since the amount of such rebates is relatively small.

- The pressures faced by private payers may indirectly increase access in Medicaid. To the extent these pressures increase private insurers’ ability to credibly threaten to decline to cover a drug when negotiating with manufacturers, they may allow private insurers to negotiate lower prices. Because Medicaid rebates are based on the “best price” negotiated by private insurers, this would, in turn, lower prices in Medicaid.